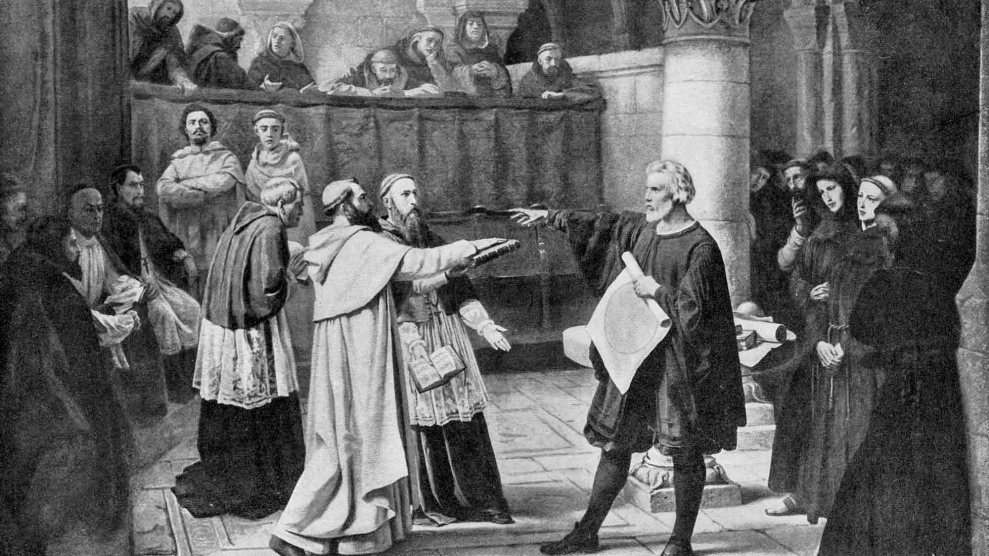

Nobody expects the House Science Committee!traveler1116/iStock

President Donald Trump’s early moves to fill the government with climate skeptics and fossil fuel interests have enraged environmentalists. His administration’s decree that Environmental Protection Agency research must be reviewed by political appointees prior to release has drawn angry criticism. But there’s another powerful Republican in Washington who has scientists worried: Rep. Lamar Smith (Texas), the chairman of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology.

Like Trump, Smith rejects the scientific consensus surrounding global warming. He wants to slash federal funding for science agencies. In recent years, he’s used his position to subpoena government scientists and accuse them of rigging climate data. In the new Congress, Smith will have even broader subpoena powers, and watchdogs warn that scientists could find themselves on his radar.

It’s unclear precisely what Smith has planned, and his staff didn’t respond to a request for comment. Democrats anticipate that one of his committee’s upcoming hearings—slated for next week—will focus on whether the EPA makes “regulatory decisions based on sound science.” Another hearing will apparently examine the National Science Foundation, a federal agency that funds scientific research. In the past, Smith’s committee has sparked controversy by investigating individual NSF grants awarded to scientists.

Conservative groups are eager for Smith to get to work. Sterling Burnett, a research fellow at the Heartland Institute, which opposes climate action, hopes the committee will hold various science agencies’ “feet to the fire to ensure everything they’re going to do is above board.” That includes, he says, pushing legislation that prohibits personal email usage for official business, an issue pushed by Smith during the Obama administration.

Burnett’s shortlist also includes requiring the EPA to consider only data that can be published and reproduced. This was one of Smith’s bills in the last Congress; it passed out of committee in both the House and the Senate but never went beyond that because of a veto threat from the White House. Euphemistically dubbed the Secret Science Reform Act, public health advocates have argued the legislation would handicap the EPA’s ability to use science to guide policy decisions, because anything that draws on confidential health data or medical records would be forbidden.

A second Smith-backed bill that never made it into law takes aim at the EPA’s Science Advisory Board, requiring that the independent panel of peer-review authors include more geographic diversity and public input—and potentially industry allies and representatives. That worries Tom Burke, a scientist and former Obama EPA official who once served on the Science Advisory Board. The panel, he says, performs vital work in the agency’s efforts to formulate the best policies to promote public health. It exists as a check on the EPA’s scientific research, and it played an important role in the EPA’s study of fracking impacts. Burke worries that “what we have seen, unfortunately, is the emergence of a very elaborate assault on science to the detriment of public health decision making.”

Smith’s tenure as chair of the science committee has been polarizing—climate scientist Michael Mann has accused him of leading a “McCarthy-like assault on science.” The Texas congressman stepped up his scrutiny of researchers and environmentalists in 2015 when he gained new power to issue subpoenas without a committee vote. Since then, he’s issued at least 24 subpoenas, some going beyond the committee’s traditional jurisdiction.

One of his most famous confrontations was with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2015, after the agency’s scientists produced a study refuting the widespread belief that there was a “pause” global warming in recent years. Smith accused NOAA of altering data as part of a politically motivated effort to advance an “extreme climate agenda.” He subpoenaed agency staffers and demanded hundreds of internal emails related to the research. The Obama-appointed head of NOAA refused to comply with the broad subpoena request.

Under the Trump administration, NOAA officials would presumably get no such cover.

Last year, Smith broadened his investigations. He took up ExxonMobil’s defense when reporting revealed that the company for years had understood the climate risks associated with fossil fuels while publicly downplaying the danger. Smith subpoenaed the New York and Massachusetts attorneys general along with a handful of environmental and science groups, charging that state efforts to investigate Exxon’s activities “deprive companies, non profit organizations, and scientists of their First Amendment rights and ability to fund and conduct scientific research free from intimidation and threats of prosecution.” Smith’s targets, which included Union of Concerned Scientists and 350.org, denounced the subpoena.

It’s unclear which of these investigations might continue into the new year. “We haven’t heard from the Science Committee since Election Day,” 350 spokesperson Lindsay Meiman said. But Heartland’s Burnett suggested that he’d expect the committee’s inquiries into the Exxon controversy to continue unless the states drop their investigations of the company. “If it becomes a non-issue in the courts, it will become a non-issue for the Science Committee,” he said.

Whatever Smith decides to investigate this year, he’ll have new tools at his disposal. Thanks to a change in House ethics rules in January, his committee will be able to conduct more depositions. In previous years, depositions could only be held if a member of Congress was available to participate. Now, Smith’s staff can depose witnesses during congressional recesses without supervision from a committee member.

Another recent House rule change, known as the Holman Rule, gives Congress the ability to target individual federal employees in appropriations bills and reduce their salary to $1. Although it’s unclear if and how Republicans plan to use the rule, it’s a potentially powerful new weapon that could be wielded against federal scientists.

All of this has the scientific community on edge.

“As general matter, chairs should use subpoena power very sparingly: when there is criminal behavior or real waste fraud and abuse, not if there are policy differences or questions about how a program is working,” says Rush Holt, president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and a former congressman. “The way the subpoenas have sometimes been used in the past is not to get the truth but really to intimidate and even threaten the recipients of the subpoenas.”

Andrew Rosenberg, who runs the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists, worries that Smith’s investigations could have a chilling effect on researchers. “People are going to say, ‘My God, maybe I shouldn’t work on anything controversial; maybe I shouldn’t risk being subpoenaed or even deposed by staff in the House,'” he says.

Still, some manage to see a bright side to being in Smith’s cross hairs.

“To be honest, Lamar Smith’s approach subpoenaing us only brought more attention to what Exxon knew [about climate change],” 350’s Meiman said. “It brought much more attention to this issue that we focus on. In some respect, I’d like to thank him for that.”