Tim Hetherington

There’s no shortage of writers who focus on the strange and dangerous things young men do. But few tackle their macho subjects with an earnest voice and bona fide investigative skills. Maybe it’s because Sebastian Junger—National Magazine Award winner, Vanity Fair contributor—cornered that market. The scruffy scribe has written about war zones from Sarajevo to Sierra Leone, as well as what he calls “necessary but very dangerous” guy jobs, from smoke jumping (Fire) to deep-sea fishing (The Perfect Storm). If Hemingway were alive, he might be reading Junger—and challenging him to a wrestling match.

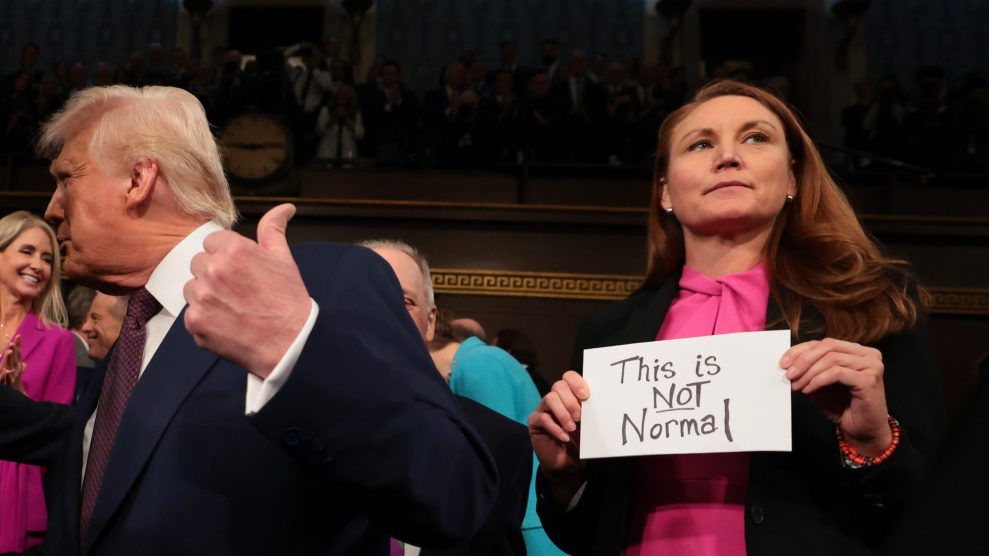

Junger’s latest project combines his dual interests. Produced with videographer Tim Hetheringon, Restrepo is a riveting documentary that charts the highs and lows of a single, all-male infantry platoon of the 173rd Airborne’s Battle Company in a remote outpost of Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley. It follows on the heels of his book, War, which describes the platoon’s experience in greater psychological detail. The soldiers of Battle saw some of the harshest fighting in Afghanistan, and ultimately it was for naught: The outpost was abandoned to the insurgents last spring.

Mother Jones caught up with Junger on an early-summer tour. Over grilled cheese, he shared his thoughts on Afghanistan’s past and future, growing up progressive, and why his preferred subjects are so darned dudely. “I felt the tug of those same impulses myself as a young man,” he said. “My journalism is part of a continuing effort to understand them.”

Mother Jones: When did your experience with these soldiers become a book to you? Did you have it in mind as a book topic at the outset?

Sebastian Junger: Yeah. I was with Battle Company in ’05 in Zabul. I’ve been in Afghanistan a lot, starting in ’96, you know, always with the populace. I was with the Northern Alliance when they took Kabul, and it looked like the end of the story. And then the war dragged on. I don’t think it’s controversial to say there weren’t nearly enough men there. And it got worse and worse. And so in ’05 I thought, alright, my country is really in this place long-term now, the story isn’t going away. And I wanted to know what it was like for the soldiers themselves. I had grown up during Vietnam. I had no connections to the US military, and I had a pretty cynical default opinion about the US military. And I was just really blown away by the sort of quality of the soldiers and officers. I couldn’t believe it.

I didn’t want to cover Iraq, partly because I just thought it was such a strategic error. I thought part of the reason I was watching Afghanistan not work was because of Iraq, and I just didn’t want to cover it. So, I thought, if Battle Company goes back to Afghanistan the next deployment, I want to cover one platoon, which is a sort of manageable number of men, for a whole deployment going back and forth. And I thought, if I’m going to do that, I can pay for it by doing magazine assignments for Vanity Fair, and they were happy to do that. And I would shoot video for ABC News, which I already had a relationship with. And they were happy for that. And I thought, that’s how I’ll write a book about a platoon. And it will be a nonpolitical book. It will just be about what it’s like to be in combat, and while I’m shooting video, I might as well shoot as much as possible, and try to make a documentary that will come out alongside the book.

MJ: In ’05, was Afghanistan a hard sell at that point? Iraq was kind of dominating the headlines then.

SJ: I don’t really remember. Graydon [Carter], I think he really trusts me about my instincts, about what’s a good story, what’s a developing story. I’d made some good guesses before, they’d sort of worked out. Stories like in Africa, Kosovo. In Kosovo, I went before it was anything, and then it just exploded into this huge international story. The same thing happened in Sierra Leone with the diamond trade. I just kind of kept guessing right. And so I don’t know what Graydon was thinking, but he OK’d it pretty quickly.

MJ: You mention Kosovo, Sierra Leone. You also shadowed Ahmad Shah Massoud, leader of Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance against the Taliban, around before anybody in the West really knew who the Taliban were.

SJ: Yep!

MJ: One of the things that makes these sorts of stories resonant, it seems, is they did end up blowing up into big political stories. And yet you tend to shy away from the political when you’re actually covering events on the ground.

SJ: Well, I mean, there’s political and then there’s just sort of a basic humanistic analysis. My reporting in Africa wouldn’t be political per se, but it’s certainly the point of my reporting—and of a lot of other reporters I know: Human suffering is bad, and if reporting stories about it brings it to light and someone does something, you know, that’s part of the point of journalism. And it’s a thin line between that and activism, and you have to be careful about that. But that was the sort of conceptual framework for me in all my reporting.

It has political ramifications, but I wouldn’t go into it with a political intent. It was really: This is happening, this is why, and it sort of begs the question—I don’t ask it directly, but it begs the question—”Why can’t the West do anything?” And in all the stories I’ve covered, the West did do something and actually brought those conflicts to a halt pretty quickly and easily.

I’m a good liberal, and I grew up in a very liberal family and had very strongly held beliefs. But I have a very complicated relationship with war, because the wars that I’ve seen were stopped by military action. So when people become just adamantly against any use of the US military, people who say that are on my end of the political spectrum, and it really bothers me, because I feel like they’re willfully ignoring suffering overseas. Suffering overseas was the hallmark of the left-wing agenda in the eighties. Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala—those were the great causes when I was in college. And it all of a sudden seems like that’s just a blind spot for the left. And it really troubles me.

MJ: That seems to have been one of the side effects of Iraq and now Afghanistan, a general isolationism, a not-wanting-to-do-anything-ism, from all sides when future conflicts may pop up.

SJ: Right. The right wing’s isolationist because, they have, in my opinion, a kind of selfish viewpoint about America and the rest of the world. And the left wing is isolationist because they’ve become very confused about the responsibility of power to take care of the powerless. Sometimes that power involves the threat or the use of force. You know, nobody’s objecting to police in San Francisco carrying guns. That’s the use of force—morally, philosophically, it’s no different. They’ve got guns, and the citizenry expects them to use those guns if it comes down to it. So I don’t quite understand the moral distinction between that and, what was it, a three-week intervention in Bosnia that stopped the genocide that had killed a quarter million people, and I don’t think one American soldier was killed? You know, I just can’t reconcile those things, and the left isn’t trying to reconcile them, and that troubles me.

MJ: You were also out ahead of a lot of people in the West when you profiled Massoud and the Northern Alliance, who were fighting the Taliban before 9/11. What drew you to that story in the first place?

SJ: I went to Afghanistan in ’96 to write about terrorist training camps south of Jalalabad and Tora Bora, in the mountains. I was there right before the Taliban took over, literally a few weeks before they took Kabul. The frontline wasn’t terribly active, but it was definitely there. And they swept into power.

Massoud was minister of defense then, and I just heard he was sort of this genius commander. I just kept tracking the Afghan story, and what evolved was this guy Massoud holding the north with a relative handful of fighters, preserving some territory against what in my mind was clearly an evil regime. The Taliban were spawned by chaos and they were kind of a solution to the chaos, but as they consolidated their power, they became more and more hideous, and more and more disliked by the Afghan people.

And so I saw Massoud as a kind of heroic figure in this story. He had his flaws obviously. But then I got the chance in 2000 to go over there—I had wanted to go over, but I didn’t have any real connections to that story. And I wound with National Geographic, this amazing photographer, Reza, who knew Massoud, and it was the ultimate “in” to that story. It was a very romantic story in some ways. I mean, here’s a fairly principled leader with a very tough group of men fighting against very long odds, against a regime that was pretty appalling. For a journalist, that’s like catnip. And my time there really affected me, and when Massoud was killed and 9/11 happened, it affected me tremendously. And I went back there as fast as I could to watch Kabul fall [to the Northern Alliance].

MJ: But despite the daring and the romance, Massoud and the Northern Alliance had to do some nasty things and get in bed with some bad people, too, like the Uzbek-born alleged mass-murderer, General Abdul Rashid Dostum. How do you bring a clear narrative to a story as murky as that?

SJ: I don’t know. [Laughs.] That’s the short answer. I mean, in terms of Massoud’s choices, I think they were practical alternatives to defeat. So my guess is, he thought we could sort out Dostum later, but right now we have to survive the next couple of years. Massoud was already—when I was there—he was already training a civil police force to maintain order in Kabul when Kabul fell. This was in 2000. The Taliban were going down. And h had convened a gathering of Afghan leaders from around the world—they literally flew in from London, and the United States —by coincidence, when I was there, I met [future Afghan president Hamid] Karzai, in a field. They just put a bunch of plastic chairs in a circle in a big field. And all of these guys who you’re reading about now, they were all there, discussing the post-Taliban Afghanistan and how to deal with it. And this is in the fall of 2000—it’s pretty amazing. So the narrative that I stuck to was really a profile of this extraordinary man. Afghan politics is so weird and complicated, and I didn’t see a need to get into the arcane details. There are other guys who do that very well, and I didn’t see a need to compete with them on that.

MJ: The Northern Alliance was a disparate collection of groups and interests, and much of the challenge in Afghanistan now is how localized a conflict it is. In War, you discuss those challenges in the context of one place, the remote Korengal Valley. What are the big difficulties of journalists and soldiers in interacting with local Afghans?

SJ: My reference point for that is 2001—I was walking around Kabul getting hugged by strangers on the street when they found out I was American. They saw us as liberators. How often does that happen? You’re hugged as an American in a foreign country, in an Islamic country, because of something your military did? That made a big impression on me, and I read later that something like 90 percent of Afghans—I don’t know who does these polls [Laughs]—approved of the US military action after 9/11. That’s how much the Taliban were hated. So my sort of starting point for evaluating the war is that the Afghans were grateful. As the war was prosecuted poorly, and undersupported and undermanned, and that approval rating dropped, that was a really tragic thing for me to watch. Because I understood why the Afghans were losing hope, but we’re also their last best hope of regaining a normal society.

People who are suffering come up with very paranoid theories about why the world works the way it does, and the theories they were coming up with about American involvement were just, like, incredibly paranoid and incredibly painful to hear. Including that we’re actually in league with the Taliban, and the whole war is a performance to conceal our deeper involvement with them that will play out years and decades from now at the expense of the Afghans. You know, it’s absurd, except that if you think that we lost 3,000 people on 9/11, and the culmination of our effort in the years that followed was 15,000 troops in Afghanistan, it really is kind of puzzling. Come on, we’re the United States, and we lost 3,000 people and those skyscrapers, and that’s only worth 15,000 men? There’s 40,000 cops in New York City alone. That’s how the Afghans see it, and they’ve been searching around for explanations and not coming up with any.

MJ: Kind of like American conspiracy theorists: Instead of just going with the simplest, most obvious explanation—government incompetence—they assume that the government is totally capable, and totally evil.

SJ: That’s right. That’s right. Like there’s gotta be some plan. There is no plan—it was Iraq. Iraq was the problem. I talked to an American military officer in ’05 who said that in the summer of ’01, he had been sent to the border of Jordan and Iraq to scout invasion groups into Iraq. And it just made me think, OK, so Iraq was in the gun sights before 9/11; the first thing Bush did was set up a plan for Iraq, before 9/11—I mean, I don’t know, I’m just basing that on what this guy said. But it seemed completely plausible, and then you watch how they handled Afghanistan, it makes it even more plausible.

MJ: Beyond the politics, though, you’ve said before that one of things you’re struck by is the professionalism, the intelligence of these professional officers and enlisted soldiers actually waging the wars. In Vietnam, it seemed like a protracted conflict demoralized the soldiers themselves and brought on a military brain drain. Does it seem to you that over the course of these wars, we’re getting a better military corps, more disposed to nuance, humanitarianism, outside-the-box thinking?

SJ: All I know is the officers I met, and they were insanely bright; they were insanely well-educated and so dedicated. They were incredibly impressive guys, and I’m sure there were those guys in Vietnam, too, but they existed in a context of ambition and apathy and incompetence; I only know that, thought, from reading things on Vietnam, so you’re going to have to trust the integrity of the reporters and the writers there. But that’s what it seemed like. I think part of it is it’s a volunteer Army now, and guys who are in the Army really want to be in the Army. I don’t know the military culture that well; I really don’t. I just know one particular platoon. And I was in a very bad place, and I have a feeling that the Army puts good units in bad places, so I was exposed to the best of the best. I know it’s not a very fair sampling. But the guys I met could have run Harvard. They were really like that.

MJ: From my experience over there, rank-and-file soldiers tend not to care much where a journalist is from, or what he or she’s done, as long as you’re not fouling up their works somehow. But you were with these troops so long; did they ask questions about your background, the things you’d done before?

SJ: Yeah, as the guys got to know me. It was after a little firefight in Zabul. Afterwards—these are 19-year-olds, you know—the guys were like, “I betcha never been in anything like that before.” And I’d forgotten this, but one of the soldiers who was there, I’d meet later in the Korengal, reminded me of it—but apparently I said, “Well, actually…” and I went on into Afghanistan ’96, the Balkans, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and they were all kind of in awe. I’d been in more combat than any of those guys had.

As they got to know me, they heard the stories. My friend Tim, my partner over there, was in a lot of combat in Liberia, and he has the video to prove it—you know, he’s a cameraman. He showed those guys some of that combat footage from Liberia [Laughs], and they were like, “That’s insane!” They couldn’t believe what they were watching.

MJ: You write in the book about trying to keep up physically with these young soldiers in the Afghan terrain and climate. Did they rag on you much?

SJ: Well, I never slowed them down, so. [Smiles] I mean, even in the best the best platoons, there’s always a couple of guys who don’t have it all together. So I was fine. But I wouldn’t have been if I’d have slowed people down.

MJ: I’ve heard from at least one reporter who’s spent time in Iraq and Afghanistan and has said, “There are no good stories on embeds.” What do you say to that?

SJ: I don’t think there are many good political stories on embeds, because you’re down there on the tactical level. It’s the same reason you don’t really need to send congressmen to remote outposts, or generals. You don’t learn much by being in the dirt, except what it’s like to be in the dirt. But that is its own story. And to me, it’s inherently interesting. When I wrote The Perfect Storm, I went out on fishing boats to understand what it was like to work on a fishing boat. And you could say, “Well, there’s no important stories out there—the important stories are the destruction of the fish stocks, the efforts to curtail the fishing industry and save the biosphere,” and so on. You could say that, but if you’re writing a book that you’re hoping to draw people into a human experience, you’d better do it on a fishing boat, or you’d better do it on the platoon level. If you’re writing headline stories for the New York Times about where the war is going, I don’t think you need to be on an embed. An embed is the ultimate local color story. But to me, that’s a very important part of the whole spectrum.

MJ: In much of your work, we’re talking about a particular kind of color story, though: soldiers in the dirt, fishermen, smoke jumpers, tree trimmers. Whence this attraction to hard men doing hard things?

SJ: I don’t know. It’s just interesting. I think human society for tens of thousands of years has sent young men out in small groups to do things that are necessary but very dangerous. And they’ve always gotten killed doing it. And they’ve always turned it into a matter of honor and a way of gaining acceptance back into society if they survived. They’ve sent these guys off to harpoon humpback whales for lamp oil. And to land a spaceship on the surface of the moon. And to take the beaches of Normandy. And to ski across the Antarctic. Whatever the hell it is, society’s been doing this since the Stone Age. And it’s a very important role for young men in virtually every society in the whole world.

And this society doesn’t do it overtly, it just kind of happens. But you go out to logging crews in the West, they’re all young guys. Fishing boats, all young guys. Combat units, all young guys. Even when they’re not being sent out to do stuff, even back home—as I say in my book—the mortality rate of young men just walking around in society is higher than if they’re a cop or a fireman. Young men take risks because it’s part of how they define themselves. And society is like, “Alright, we need risks to be taken, because we need oil to be drilled off the Gulf, we need wood to build our houses, we need this, we need that, so have at it, go ahead.” So society and the genetic programming of young men converge in this.

And to me, it’s an interesting story, partly because it’s so ancient. I think it reveals some very powerful and raw truths about human beings. And I felt the tug of those same impulses myself as a young man. I tried to understand them, and my journalism is part of a continuing effort to understand them.

MJ: What were some of those experiences that you had before you sat down to write about other people’s stories?

SJ: You know, I hitchhiked across the country once. Which is no big deal, but I was from a suburb outside of Boston; I’d never been west of the Hudson River, so it was a pretty intense experience. I worked as an arborist, a climber for tree companies; I got hurt doing that. And you know, the usual teenage shenanigans that involve the law and risk of injury. Nothing evil, but definitely troublesome to the authorities. In that sense I think I was pretty healthy, psychologically, in that.

MJ: Do you think that “boys’ life” used to be more mainstream in American society? It’s a perennial lament that we’ve gone soft, that there aren’t a lot of people now who are going off to college and doing these sorts of things.

SJ: Look, it’s a recession: There will always be people to fill those jobs. Not everyone has to be a badass. [Laughs.] You’ve just got to have enough guys to drill for the oil that we put our cars to drive around, or whatever. You know, I think that’s probably always been true. If the entire society was like that, it would be a completely dangerous, unstable, militaristic society, and I think it would last very long.

MJ: In the small group of guys that figure prominently in War, Sgt. Brendan O’Byrne clearly pops out as the main protagonist in the story, and you’ve had a lot of interaction with him since he came back from Afghanistan. Was he typical of everybody else in the platoon?

SJ: No, he really wasn’t. I think the guys—not all of them, but a fair number of them—thought about what they were doing in complex terms. But few of them articulated those thoughts. They all had doubts; they all had worries; they all had things they were proud of. But they didn’t always put the words to them.

And O’Byrne—Brendan—he’s a very smart guy, but his education was not perfect as a teenager. I think he was pretty ADD as a kid, and his family was definitely troubled. But he just had a way of talking about these things that was so insightful and human. He didn’t default to the sort of standard military line. He’d say, “What about those guys we’re fighting? Are they on their hilltop thinking about us? ‘Cause I’m thinking about them!” We’d be out on some ambush, and it’d be cold. “You know, it’s cold as hell tonight. They gotta be cold, too!” He would just do that in his mind, and because we could to know each other pretty well, he would speak those thoughts. And he just had some very interesting, complex things to say about the nature of killing, and of brotherhood that was out there. He was just an interesting guy to talk to.

MJ: In your experience, how do these guys—not just Afghanistan soldiers, but fishermen and the rest—handle it when they come home, and find television, pop culture, families, a society that’s not of that world?

SJ: Well, you know, we’ve all read the papers and seen how that goes. The guys I was with, they didn’t come home. They stayed in the 173rd or they went to other units and they deployed again. About a third of the platoon is back in Kunar province, fighting very close to the Korengal, and they’ve been there since last December. They’re soldiers. They had come back to their base in Vincenza, Italy. They call their base “Coward’s Land,” because, I think I say in the book, guys who weren’t in combat can order around guys who were, and that’s such a reversal of the natural order of things in their minds. It drove ’em crazy.

And I think it made them doubt these rules, these social rules, that were so reassuring out at Restrepo. It was such a dangerous place, and everyone had their job, and everyone knew how they fit into the group, and really nothing mattered except that you were prepared to risk your life to defend everyone else. If you did that, everything else was a footnote. And then suddenly they come back to society, and the footnotes are what people are reading when they meet you. “Are you good-looking? Are you smart? Are you educated? Is your dad rich? Is your girlfriend hot?” All of a sudden all that stuff becomes more important than things that were actually keeping them alive out there. And it’s really confusing. I think it gives them a feeling of irrelevance. It’s one of the reasons they stay in the Army and go deploy again.

MJ: In the book, you discuss how these guys cope, or don’t cope, with family issues back home while they’re in the field.

SJ: They didn’t have any communication up there, so in a weird way I think it was a little bit easier for them. Once a month, they got to talk with home, and I think it was hard for them to gear back to the lack of seriousness that civilian life involves. And those were the lucky guys; the unlucky guys had really serious problems on the home front. They had parents who were dying and getting divorced, and wives who were leaving them, kids who were failing. I think those are the guys who were really having a tough time.

MJ: While reporting, you’d rotate out to go home for a month at a time. Did you have trouble readjusting and catching up with what everybody in the platoon had been up to while you were gone?

SJ: For sure. But I knew I couldn’t be out there forever. I wouldn’t have wanted to be. And I knew those guys well enough that it would just be straight-ahead journalism, you just asked people what happened, and you’d confirm it with someone else, and you had a pretty good idea what you missed. So I definitely understood that I didn’t need to be there for absolutely everything. Some of the best sections in the book, I think, I was not there for, and I got them through video that Tim had shot, and through interviews with the men, and what I was getting was how they had processed it in their minds. Which is a certain kind of reality. So when Steiner got hit in the head—I wasn’t there for that. I wished I had been. It was a hell of a firefight. And it would have been amazing on camera. But I wasn’t there. And the story that he told me was pretty affecting in its own way, and I wouldn’t have had that story if I’d been there. It would have been in some ways a very shallow interpretation of what had happened.

MJ: Everybody in uniform tells their salty sea stories, and as you get more and more distant from the event, the stories get bigger and saltier. Were frontline soldiers a little more honest to you, or did you still find a lot of sea stories along the way?

SJ: What was going on out there was so outrageous that I didn’t get the sense anyone was embroidering things much. I don’t know what they’re saying now, but if you just report the literal truth, that was already so over the top, they were content with that, probably.

MJ: One of the truths you report in the book is that war is a very boring thing for very long stretches of time. What kind of challenges does that pose in telling a story about this experience?

SJ: Well, you know, in the down time was when things would suddenly come out. Interactions within the platoon, things that revealed some of the stresses of being out there. Combat is very intense but it’s sort of monochromatic. It’s kind of all the same. It’s not a very subtle thing; I don’t think there’s much to discover out there. For my intents and purposes, the firefights started to blur together. And when it got interesting was when you saw the guys deal with each other when they were under the tremendous stress of not having any combat. Once you’re psychologically geared up for combat, not doing anything is terrifically hard. And that was an interesting kind of a social experiment: Stress some guys for five months, then cut out the fighting, and leave them on a hilltop for the next three-quarters of a year and see what happens. That’s a fiendish experiment, but it was pretty interesting.

MJ: In your writing, you fill a lot of that down time with information from a lot of psychological and scientific studies the government has conducted about life under fire. Did those just start as what-ifs as you were observing human behavior yourself?

SJ: I just became interested in courage. It’s this sort of mythic thing that civilians talk about. Soldiers never talk about it. But clearly it’s happening. And I just started to think of it as a profound choice that a person can make, where your welfare is more important to me than my welfare. The group is more important to me than me as an individual, and if everyone feels that way, we’re all going to be better off.

I had this idea that only humans do that. I mean, there were herd animals that engaged in collective defense, and there are animals that protect their young, obviously—good genetic choice. But the decision to suicidally defend your peers against attack, where their death is more upsetting to you than the prospect of your own, that’s a human thing. And once I started to think about it in those terms, I felt I was getting to the heart of it. It’s very hard to define human. We use tools. Yeah, so do chimpanzees. We understand death; so do gorillas. We cooperate with each other; tons of animals do that. I thought I was sort of narrowing in on something that’s uniquely human. It is that kind of altruistic behavior for a peer you’re not related to.

And to help me in understanding this I just went looking into the scientific literature, and what kept coming up were military studies. Because, of course, some smart guy behind a desk realized that if they could figure out what gets men to act courageously, they have an advantage over another military with the same number of men who are not gonna act courageously.

The stuff that was coming out of these studies was so interesting and counterintuitive, like the fact that fear is connected not to the level of danger but the level of perception of control. So if you’re a fighter pilot in World War II, with a 50 percent cumulative casualty rate, fear is less of an issue than in a rear-based unit with a much lower casualty rate but guys with no real control about when they’re occasionally bombed. That’s fascinating, and it explains why people are less scared of driving, when they’re in control, than when they’re flying where they’re much safer but have no control. It went into the book because I just couldn’t help myself.

MJ: You wrote in the book about the distinction between the fear and the anticipation, about that being a function of control.

SJ: Yeah. Brendan said to me at one point—he just had a knack for saying stuff that was so trenchant and right on—he said, “You know, some of the scariest stuff out here never happened. It was the attacks that we were expecting and never materialized, and the hours and days before that attack. The operation that got aborted at the last minute.” That stuff was terrifying, compared to once it was actually going on, when there wasn’t really room for terror. That was such an insightful thing that he said.

MJ: You reviewed Karl Marlantes’ Matterhorn in the New York Times Book Review, a newly completed novel of a Vietnam soldier’s experience. Drawing parallels between Vietnam and Afghanistan has become fashionable. In War, you discuss having these “Vietnam moments” of collective wishful thinking, fostered by a military PR machine.

SJ: These guys are over there, the public affairs soldiers and the colonels, everyone in charge, is over there to do a job. And it’s completely understandable to me that they things they say present the job in the best possible light. You go talk to BP right now, it’s going to be the same thing. You talk to a kid who’s in trouble in school, not doing his homework, he’s going to do the same thing. It’s just human nature. I get it. I think it’s only dangerous if you’re not aware that that’s happening. I think it’s also very dangerous on the side of the press to be so endlessly cynical about the military that you don’t believe a goddamned thing, and you just assume you’re getting lied to all day long. It’s unfair, it’s destructive, and it’s bad journalism.

So I feel like you have to talk about that optimism in the context of its counterpart: the cynicism of the press. They really are two sides of the same coin. And I think that cynicism came out of Vietnam where they were lied to all day long, you know? The whole war was a lie. The Gulf of Tonkin was a lie. The whole goddamn thing started with a lie, and it spurred 10 years of lies.

Afghanistan didn’t start with a lie. We really did lose 3,000 people. It really happened. The towers aren’t there, you know? And Bin Laden really did do it. And he was in Afghanistan. There’s no lie there. But I think the press has a kind of hangover. Vietnam was almost now a kind of journalistic myth. And we all grew up on that myth, we all read Michael Herr’s Dispatches, and it set up this paradigm that I think the press has actually been more reluctant to move on from than the military is.

MJ: You bring up Michael Herr. Whether people you’re reading today or just influences in the past, who are the guys that really did stuff, wrote the stuff that made you want to get into this in the first place?

SJ: I mean, the people that I read when I was young were John McPhee, Joan Didion, Peter Matthiessen, Barry Lopez—great, great, great nonfiction writers. The best, you know. Those are the people I emulate as a writer. As far as war reporting, Kapuscinski is amazing; George Orwell—Homage to Catalonia is incredible; you know, Hemingway was a novelist, but it’s pretty damn compelling stuff. Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls is incredible. It’s not journalism, but it feels a little bit like it. Michael Herr, absolutely. Tim O’Brien, again a fiction writer, but amazing.

MJ: In your own work, there’s also a certain economy of speech, of words, that you’ve always been really bound up with. Is that a Hemingway thing? Who else is at play there?

SJ: John McPhee. Asolutely. I mean, I think in sports, in art, in writing economy of motion is—it just is. You know, if you design a machine to do something, the fewer moving parts it has, the better a machine it is. And I think that’s true in the arts as well. And definitely for me it’s true in writing. I think that’s the basis of good design in almost anything. And writing is partly a matter of design. It’s like almost engineering—or engineering with words. Like, how do I get this done the most efficiently, with the fewest possible extraneous movements. How do I construct this paragraph to do what I need it to do without wasting the reader’s time?

MJ: Has it now gotten natural enough, are you confident enough in your voice, that it comes out pretty well the first time? Or do you find yourself chop, chop, chopping?

SJ: No, it comes out. I mean, obviously, like everyone, I edit. But it’s not a laborious process. I’ve just been doing this a long time now, and it comes out pretty smoothly actually.

MJ: I’ve heard a lot of people complaining, especially since Iraq and Afghanistan kind of broke out and became our paradigm for wars, how much harder it is to make your bones as a stringer. To get out there and just go places where you think the stories are and to establish yourself as a freelancer to begin. What kind of advice would you have for somebody who wants to be parachuting into Africa or… other conflict hotspots?

SJ: Well, the networks and cable news are in a state of crisis, and no one can afford to maintain a journalistic presence in any of these countries. The insurance is too high. The rates for union camera work are too high. It’s hundreds of thousands of dollars a week. Like, no one can do it. It’s over. In the eighties, I don’t know, maybe that was true, but the networks were making so much money that it didn’t matter. But now it matters because they’re getting killed. And so actually I think there’s a real opportunity. Like, if I were 23 years old, I would move to Kabul. ABC can’t keep someone there, you know? I mean, I think they have someone there right now. But it’s a very tenuous connection that the news bureaus have with these foreign stories. They just can’t maintain it. And even if there’s an ABC correspondent out in Afghanistan, he can’t be everywhere.

And I think if you buy a video camera, a good video camera, and you learn how to shoot video, and you can move it through your laptop on whatever the electronics are required—I never file from over there, so I don’t even know how that shit words—but if you figure the technological aspects of it out, and you get a sat phone and a bulletproof vest, and you move to Kabul and you just hang out looking for good stories, and approach the networks and the newspapers—I mean, the trick is, you file three minutes of footage for ABC, you get $500. And then you file a story for the Boston Globe—they definitely can’t afford to have anyone there full-time—and you get $800.

You can do it. I think actually, in a weird way, the financial collapse of the news business has opened possibilities up. In the eighties, all the major newspapers had bureaus all over the world. Try to break into that. In Bosnia, Jesus Christ, it was hard. They all had their paid guys there. They don’t anymore.

MJ: So you see self-financed conflict bloggers like Michael Yon actually being kind of like a model for young journalists these days?

SJ: Yeah, I mean in the sense of multitasking, multimedia news provider, yes.

MJ: I had a “Covering Conflicts” professor in J-school. In the middle of our class she left for like three weeks to go over and cover Kashmir. Shot amazing video, did some ridiculous stories, couldn’t find anyone to buy it. She ends up giving it to somebody for pennies on the dollar.

SJ: Well Kashmir’s not—

MJ: Sexy.

SJ: Yeah. I mean, nothing’s happening there, it’s a 30-year stalemate. In ’94—was it ’94? No, it was later than that—in ’98, the Kargil offensive killed hundreds and hundreds of Pakistani soldiers. I mean, they were coming at the Indian positions like full-on, World War I-style, fixed bayonets. I think it was ’98. Then it sort of popped up in the news, and then it subsided again. So unless you catch one of those…

But my guess is that when Haiti happened, my guess is that there were freelancers down there that were getting work. The ones that got on the plane first and got down there. I’m not doing that kind of work anymore so I don’t know for a fact; it’s just my guess.

MJ: But it sounds like, in addition to having multimedia chops and a good news nose and the wherewithal to handle the logistics, there’s a certain amount of marketing savvy that’s got to go into it, too. Just in terms of converging your interests with what the outlets want.

SJ: Well look. I mean, there’s permanent stories like Iraq and Afghanistan, particularly Afghanistan. Then there’s sudden tragedies like Haiti, and you better be prepared to leave, like, that afternoon. And then there’s these hidden stories that are really interesting and no one’s—they’re kind of below the public knowledge. And as a feature writer, you want to dig them out and offer them up to GQ or whoever. Like, who knew that there’s transvestite truckers in Congo? Whatever, I’m just making that up. [Laughs.] So those are the three food groups of freelance reporting.

MJ: Where would you be if you could jet off right now to a spot?

SJ: Oh, god. Afghanistan’s always interesting to me. I’d probably go to Kabul. But that aside, northern Mexico is pretty intense right now. It’s sort of turning into Colombia. Except it’s on our border. It’d be a really dangerous story to do, but it’d be kind of interesting. Not a bad place to place yourself would be Nairobi. There’s a lot of stuff going on in East Africa. Somalia, Yemen. I mean, you’d have to be prepared to get on a plane and fly around, but at least you’re in the area. And you could cover Uganda. There’s all kinds of shit going on out of Nairobi. It’s a dangerous city. It’s probably pretty expensive. But that to me would be pretty interesting. I don’t know anything about Asia. Well, Moscow. Moscow, there’s a lot of stories on the edges of the former Soviet Union, and Moscow is a very messed up country and a very big player, and is going to be important for a long time. And if you were prepared to make a multi-year commitment as a freelancer, and you really got to know Russia and learned Russian, and were prepared to fly down to Tajikistan or wherever to cover that stuff, I think you’d get regular work.

MJ: Just then was the first time I heard you mention, from a journalistic standpoint, that there’s danger there. Obviously it wasn’t as much of a consideration for you now, going on embeds, but that’s still something that a journalist has to prepare for now logistically—getting your contacts, getting your stringers, getting people that you trust. When’s the last time you had a really hairy experience?

SJ: Well, in Nairobi, there’s just a lot of street crime. And Mexico’s obvious. But I was in Nigeria, and that was terrifying. There wasn’t even a war going on, but it was such a volatile, violent society, it was so poor, it was so on edge. I was in the Niger Delta, and the social issues there are so outrageous. I just felt like every day I was—and then the government, we were getting followed around by these government spies. It was pretty clear who they were. They were just idiots. And so you didn’t know who to hide from, the oil rebels or the government. You were kind of hiding from everybody. That didn’t feel very good.

MJ: I always hear from foreign correspondents about the camaraderie between journalists. And obviously you had Tim out there with you in Afghanistan. Have you made friends for life out there in the journo community? Do you keep tabs on these guys when they’re going out?

SJ: Yeah, Tim and I are great friends. I think any war reporter, almost by definition, is a complicated personality, myself included. And those people are very, very mobile, and so they’re friendships that take place sporadically and intensely, and then they get truncated for the next couple years until you run into these people again. Tim lives in New York, and we’re friends, and he’s nearby. But the guys I met in Bosnia—my friend Harald [Doornbos, of United Dutch Newspapers], I haven’t talked to him in a couple years, but largely due to him, in Bosnia, I’m doing what I do now. I showed up there clueless, I met Harald in an elevator—he’s a Dutch reporter, and he was just going from freelance to a real steady paying gig, which made him in my eyes a complete god. I’m like, what? You’re getting steadily paid to report the news? Can I kiss your hand? I just couldn’t believe, you know. He was younger than me, but he was more experienced and he took me under his wing. And we hung out, became good friends, and I haven’t talked to him in a couple of years, but he totally changed my life

MJ: You see everyone talking about going from freelance to full-time paid. So, at the point where Nat Geo and Vanity Fair start banging down your down, is there kind of a “What the fuck” moment there?

SJ: Well, that happened after The Perfect Storm came out. So I already had this sort of weird success that I hadn’t anticipated. I remember sort of thinking, almost regretting, that I would work so long to be able to make a living as a freelance magazine writer overseas—I wanted to do that for so long, and it took so long to get there. And by the time I finally got there, financially I didn’t need to. Because I was a successful author. So it kind of, it took away some of the gratification of it. It wasn’t a huge financial relief, because I had already solved that problem.

But it’s the work that I think is incredibly—I just feel incredibly lucky to be able to do it. And I feel there’s a lot of honor in it. That I was accepted into this sort of small world of foreign reporters, to me, had nothing to do with the money or anything. It was just such an honor. I was just so thrilled. And it’s the thing I’m really proudest of. I’m proud of my books, but not quite like my foreign reporting. This book is foreign reporting, so the two kind of converged on this one. And it’s first person, it’s a very personal book. A lot of things converged on this that make it very different from anything else I’ve ever written.