Photo: Mindy TuckerPolitical satirist Lizz Winstead was shouting at the TV long before it was cool. In 1991, watching CNN’s coverage of the first night of Desert Storm on a bad blind date, she looked around the rapt sports bar in horror and had an epiphany: “Are they reporting on a war, or are they trying to sell me it?” Thus began an obsession with “breaking down the media breakdown” that eventually led her to co-create The Daily Show.

Photo: Mindy TuckerPolitical satirist Lizz Winstead was shouting at the TV long before it was cool. In 1991, watching CNN’s coverage of the first night of Desert Storm on a bad blind date, she looked around the rapt sports bar in horror and had an epiphany: “Are they reporting on a war, or are they trying to sell me it?” Thus began an obsession with “breaking down the media breakdown” that eventually led her to co-create The Daily Show.

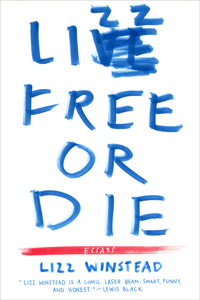

In her new essay collection Lizz Free or Die, Winstead tracks her evolution from the perpetually “unladylike” youngest daughter of a large Catholic family in Minnesota to a comedian who found “a way to use humor to speak truth to power.” She writes of getting knocked up by her hockey player boyfriend in high school, spending a fortune on her dogs’ waste problems, and saying goodbye to her dying father with understated insight and, of course, humor—reminding us of its value as an antidote to both political and personal hardship.

These days, Winstead is busy touring the nation doing stand-up shows to benefit Planned Parenthood and gearing up for general election season. (“It is my favorite time to be out on the road,” she says.) I caught up with Winstead to talk about our lazy media, uterus-related legislation, and that time she got replaced by Jerry Springer.

Mother Jones: Tell me more about your moment of revelation while watching TV coverage of the first Gulf War.

Lizz Winstead: I remember watching the Vietnam War as a kid and seeing shooting and blood and bodies—and people were very serious. And then when I sat down [on the first night of Desert Storm] at that bar—and the bar atmosphere and the graphics and the theme song and the green light and the hot people. I wasn’t looking to analyze—it just all seemed like a movie. And I remember being so struck by the fact that they were trying so hard to sell me this war. And then to have this goofy date that I was with be like, “Wow, this is so cool!” And I was like, “Sold! Sold to you. You just bought it.” That was really crazy to me, that they could make something so serious so cartoonish. It was just like, “Oh my God, what is going on here? This is awful. How come they don’t have a person on saying, ‘This is awful’?” Instead they just keep reporting how great it is from 700 different people. There’s just one side and we’re all supposed to be on it. And patriotism is news. So, from that point forward, I just thought I’ve got to pay way more attention because it’s too crazy to not respond to.

MJ: The media landscape has obviously changed quite a bit since then. For better or worse?

LW: Well, when there’s more of it and it’s on 24 hours a day, it’s gonna get worse. There’s just no question about it. There’s a lot of, “We’d rather be first than right.” A lot of breaking stories without facts. And when it comes to television news, it’s a lot of commentary and not a lot of reporting. You have people having conversations on couches. There’s a lot of wondering aloud and supposing and not a whole lot of introspection and fact checking. And so people tune in and out in a way that’s getting little bits and pieces of half of the truth.

MJ: It’s been said that young people get their news from The Daily Show. True? Good? Bad?

LW: Yeah, people have told me that themselves—that they get their news from The Daily Show. I think it’s always problematic when anyone says, “I only get my news from…” You should be getting your news from a bunch of different places. You should actually be reading longer pieces, where somebody did a whole bunch of research or was, you know, in the Sudan or Syria or wherever. When one only gets their news from a place that is, for the most part, looking through a satirical lens at how poorly we’re actually receiving information—I mean, that gives you a catharsis. But people need to get information to make themselves smarter, not just to make themselves feel good that someone is actually watchdogging the media.

MJ: Mother Jones interviewed you in 2004 when you were helping launch Air America. What did you take away from that experience?

LW: It was such a gigantic, ambitious task to put on 18 hours of programming every day and to get it all launched and ready to go in seven and a half months. I keep finding myself in these professional situations where somebody has given me a job I’ve never done before and I’m supposed to know what I’m doing. That’s what happened at The Daily Show, and that’s what happened at Air America too. It was a lot of people trying to figure out a lot of things and trying to get a message on the air. And because the radio airwaves at the time—and I don’t think it’s gotten much better—were like 91 percent conservative talk and 9 percent progressive talk, people were starving for any other side of the story. You could never keep anyone happy, because there was such a void that people were panicking.

The people who had launched the network in the beginning said they had money and then they didn’t have money and then we were like, “Oh my God, they really never had money.” So we were trying to stay afloat and get the programming out. But what was so amazing was that through the crazy turmoil of transition, no one quit. People were helping other people pay their salaries and make it work. The commitment to keep the message out there was the biggest takeaway from it. It was really a joy.

Working with Rachel Maddow and Chuck D every day was super fun. We had this little team that put on a show that was really fun and then we got canceled and replaced with Jerry Springer. And I got fired. We had new owners and new managers come in and they said comedy doesn’t really seem to be an effective tool to get people listening. I was like, “Since when?” It was kind of absurd. You know, one of the things that I never thought would happen to me is that I would be replaced by Jerry Springer. Like, I just thought I’d made different choices in my life.

MJ: In the book, you write about being an aspiring comedian in Minneapolis when there were just a handful of women in comedy. As your jokes started to shift more towards asserting your opinion, audiences got uncomfortable. Say more.

LW: It was such a subtle thing. I was kind of just going about my business, telling my little observational jokes. And then all of sudden I was having bad shows with material that had normally worked pretty well. And I was like, “I don’t know what I’m doing wrong. Am I dropping out vital information? Am I just low energy?” So I started taping the shows and when I listened back, I realized I had just shifted the introduction to the material in a more declarative way. “I think…” instead of saying “I feel…” I would say “I think…blank blank blank.” And it could be, you know, “I think Hitler sucks.” But the fact that I was saying “I think,” I would feel this recoiling—mostly from the men in the audience.

The covert message I kept getting back was: We will deal with a woman on stage if she can talk about how fucked up she is, how wrong she is, how shitty she feels about herself. But I don’t talk about that. And the fact that I don’t present myself that way, even when I’m saying things that are not threatening, threatened people. Simply by the fact that I’ve formed a clear opinion. You can only imagine once I started having opinions about politics and the world—that was really awesome to stand in front of a group of people shoving buffalo Cheetos, or whatever the hell they got a big basket of, in their face as they watched comedy.

MJ: So have we evolved a bit since then?

LW: Yes, I think so. The good news is that now we have an entire generation of men and women who’ve been raised in the ranks with there being a substantial amount of women doing comedy. So the shows I do now around New York have plenty of women. I think if you still have TV shows that are run by men that are really old-school, you’re still gonna have old-school problems. But as shows start coming up where younger men and younger women are running those shows, I think they run them the way their lives are—which is full of men and women. Which is great.

MJ: How’s the Planned Parenthood tour been?

LW: The take-home for me is that women rally when there’s a crisis. To me, Planned Parenthood—and the discussion about reproductive rights and health—needs to be part of your routine. Like going to yoga. Or breathing. You can’t just jump in when some horrible thing is about to go down. We cannot live in crisis mode. It needs to be this living, breathing thing. I wish that every city in America would stand up and say, “Planned Parenthood, we are so glad you are a part of our community. Just know that you can always count on us being there. We will be your champion. You will not be fucked, because we have your back.”

People who work in reproductive health care can’t be doing the heavy lifting and be the ones to [defend themselves] as well. The women who use the services and are sexually active and who use birth control and use these clinics have to be the people who say, “Part of being a human being is being a sexual being. And we’re not embarrassed. And we’re not going to mask that we’re sexual beings.” I’m tired of trying to dance around everything—even in this discussion that the country’s having about birth control. It’s incredibly valid that people use birth control for many other reasons other than just birth control, but we need to tell people that people use birth control for endometriosis first and then kind of slide in the sex thing, “Fuck that. It all needs to be valid.”

MJ: You write about accidentally getting pregnant as a teenager, having a terrible experience at a crisis pregnancy center, and eventually getting an abortion. What motivated you to speak out?

LW: One thing was that the story is not extraordinary. It’s happening to women all the time. It’s happening to young girls who don’t know any better. And they wander into these awful places, pregnant, and they don’t have any information and they’re demonized by these awful people. And I think that the more women start having a conversation about abortion and about the lack of information that we provide, the more normal it becomes. I had so many women come up to me and say, “I have a story that’s so similar and I want to start telling it now.” I would never tell someone to tell their story, but hopefully by telling mine it will encourage you to make the decision on your own. Every time you tell your story, someone has to put your face when they are saying something hateful—or the face of their sister or their mom or their cousin or their coworker. If people know that people have abortions and go to Planned Parenthood and get birth control, it’s no longer that “bad” people have abortions. It’s that people have abortions—because they have to make a choice about how they’re going to move forward. [Click here to browse all Mother Jones coverage on reproductive rights.]

MJ: Between the Komen Foundation defunding Planned Parenthood and transvaginal ultrasound laws and the controversy around no-cost birth control coverage, it seems like there’s always something going on with reproductive rights these days. Thoughts?

LW: Yes, there’s always someone trying to decide something about my crazy-ass uterus! Which I don’t really understand at all. I mean, I don’t know how you arrive at: Your boss gets to make moral decisions about what kind of health care you have in your insurance plan? Like, that’s the world we live in. But I think that women aren’t taking it sitting down anymore. I think the Komen thing slapped them in the face. In Virginia, many people thought it was fine to propose a law that says you can have something shoved in your vagina against your will. And a lot of people didn’t seem to have a problem with that. I mean, it shocked enough people—except apparently Rick Santorum who fights on in this deafening world that is his own. It’s astounding to watch actually. I haven’t seen anybody with that kind of commitment to his conviction in a long time in politics. It’s certainly not a conviction that I believe in, but at least I know why I hate Rick Santorum. He’s made it perfectly clear.

MJ: So as a comedian, were you hoping Santorum would be the nominee?

LW: To me, it’s just all very frightening. Comedically, they both seem to be just fine. I’m not that worried. My worry, honestly, was that with this many in the race, it was just that much more disinformation that went unchecked. At least if it’s one dumbshit saying stuff, you can go, “Oh, there’s this one dumbshit who keeps saying stuff.” But with three or four of them just constantly blabbing, it’s a wall of crap that just keeps getting spewed. [Politics] just keeps getting weirder and weirder. At one point it may actually put me out of business because it may become a joke that you can’t make a joke about. That’s frightening.