<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/glass_window/371450249/sizes/l/in/photostream/">scott*eric/Flickr</a>

After three years, the bipartisan Commission on Wartime Contracting completed its business this week. In its final report to Congress (PDF), it estimates that the federal government has lost between $31 and $60 billion to contractor fraud and waste since the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq started. “The government was not prepared to go into Afghanistan in 2001 or Iraq in 2003 using large numbers of contractors, and is still unable to provide effective management and oversight of contract spending,” said commission co-chairman Michael Thibault.

Beyond its bureaucratic title (“Inattention to contingency contracting leads to massive waste, fraud, and abuse”), the most interesting chapter of the commission’s 248-page report reads like a greatest-hits list of expensive bloopers that make that famous $600 Pentagon toilet seat look like a bargain. In ascending order of egregiousness, here are the top 10 war-contractor boondoggles detailed in the report:

10. Welfare for warlords: When the Pentagon hired Afghan big-rig drivers to transport supplies as part of its Host Nation Trucking program, it forgot to guarantee the truckers’ safety. So the truckers spent as much as 20 percent of their contract money paying off local bad guys for protection. A 2010 congressional report titled Warlord, Inc. (PDF) concluded that “The HNT contract fuels warlordism, extortion, and corruption, and it may be a significant source of funding for insurgents.”

9. The world’s most expensive road: In 2007, US planners decided to pave a 64-mile mountain road between the Afghan towns of Khost and Gardez. They figured it would take $69 million to complete, but the cost swelled to $176 million. Much of that was spent on security, including a lot that went to a local big-swinger known as “Arafat,” who’s now believed to have been working for the insurgents. In May, the New York Times reported that “a stretch of the highway completed just six months ago is already falling apart and remains treacherous.”

8. This old base: In the fall of 2007, the Air Force gave $18 million to contractor CH2M HILL for construction work at Camp Phoenix, an Army installation in Afghanistan. The firm hired a shady subcontractor who didn’t pay his workers and fled the country with $2 million, which he used to build himself some villas abroad. The unpaid workers walked off with a bunch of generators and other materials. The delays left hundreds of NATO troops without suitable housing for a year and a half. When the contracting commission’s Thibault visited the soldiers in their temporary digs, they alerted him (PDF) to the shoddy electrical work: “I just walked in the room and I’m talking to some of the people living there and they say, ‘Sometimes when you put the plugs in, if you don’t have the right extension, it’s just like a sparkler.'”

7. Rent-a-ripoff: Coalition bases in Iraq and Afghanistan tend to be big and rugged, so many units rent locally owned four-wheel-drives for troops to get around the installations. A 2010 survey of US forces in Afghanistan found (PDF) that the Army was spending $119 million annually to lease about 3,000 cars—roughly $40,000 a year per car. Last year, the General Services Administration found that the military “could lease and maintain 1,000 vehicles for about $19 million per year,” or 16 percent of what it had been paying. Nevertheless, the Army still considers paying a premium for rental cars to be strategically necessary; it’s even listed as “civic support” in a manual titled “Money as a Weapon System” (PDF).

6. The Kabul bank bust: This thing’s so screwed-up, we wrote a whole explainer about it. Since 2003, the US Agency for International Development has paid $92 million to the accounting giant Deloitte to train executives of the Afghanistan Central Bank. The Central Bank oversaw Kabul Bank, Afghanistan’s largest private bank, which had an estimated $900 million in assets loaded with worthless loans. Unsurprisingly, the bank collapsed in 2010, taking the nascent Afghan financial system down with it. (Kabul Bank’s founder and CEO explained: “What I’m doing is not proper, not exactly what I should do. But this is Afghanistan.”) In effect, USAID paid a Wall Street firm beaucoup bucks to fiddle while the Afghan market burned. “USAID staff learned of serious bank problems from reading about them in the Washington Post. Deloitte never notified the agency,” the contracting commission reported.

5. Never leave a mandarin behind: In 2005, the Defense Logistics Agency awarded Swiss-based Supreme Foodservice a fat contract to ship “vitally needed” food to bases in Afghanistan. By the early 2011, the company had billed the government $4.2 billion, but Pentagon investigators found that sum had been padded with hundreds of millions in possible overcharges for things like providing “premium airlift” of fresh fruits and vegetables from the United Arab Emirates. Nevertheless, the company got a two-year extension on its contract, perhaps because the Army general who used to supervise Supreme’s DLA contract is now president of the company’s US division.

4. Soldiers of misfortune: To keep their profit margins fat, military contractors tend to subcontract on cheap labor from poor nations, a practice that’s led to “forced labor, slavery, and sexual exploitation,” the commission says. In a trip to Iraq in 2009, commissioners learned about the mostly African and South American guards hired by companies like Triple Canopy, SABRE, and EODT to provide security on big US bases. Among their discoveries: Guards were often ill-equipped, worked unusually long tours with 12-hour shifts, were denied their one-month vacations, and weren’t paid until their contracts were finished, essentially forcing them to endure their assignments to the end. The government paid SABRE $1,700 per guard; in turn, SABRE paid its Ugandan recruits $700 a month and pocketed the difference.

3, 2, 1. KBR, KBR, KBR: According to the contracting commission, megacontractor KBR (a.k.a. the contractor formerly known as Halliburton) was paid at least $36.3 billion to provide base support in Iraq for the past eight years. That’s slightly less than the government bailouts for Bank of America and Citigroup. But then, the banks eventually returned the money. The commission report details numerous examples of waste by KBR. Where to begin?

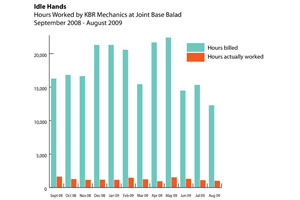

There’s the kickback from the subcontractors who were awarded a $700 million dining deal in Iraq. (The Department of Justice has filed a claim against KBR for that.) Then there’s the $5 million spent on 144 KBR mechanics who worked as little as 43 minutes a month, on average. Inspectors have found that KBR can’t account for $100 million worth of its government-furnished property in Iraq. Despite collecting $204 million for electrical work on Iraq bases, KBR’s shoddy wiring has been blamed in as many as 12 soldiers’ electrocution deaths, including a Special Forces commando who died after he was shocked in a shower stall. The company has also billed Uncle Sam a half-billion dollars to hire Blackwater to provide personal security in Iraq, a big contractor no-no.

Perhaps most troubling is the company’s links to purported human trafficking. In late 2008, reporters discovered a windowless warehouse on the Camp Victory complex outside Baghdad, where about 1,000 men from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka were being held in prisonlike conditions. The men had been hired by a KBR subcontractor. Around the same time, another KBR subcontractor was sued for allegedly spiriting Asian workers into Iraq with false promises of high-paying jobs.

And the waste continues. When the troop drawdown in Iraq started, writes the commission, “KBR accounted for about half of contractor personnel in Iraq. When bases closed and its personnel left those bases, KBR merely transferred some of them to other bases and continued to bill for their support.” In all, KBR has cost the government at least $193 million in pay for unnecessary personnel, and maybe as much as $300 million. However, the Pentagon is in no hurry to give KBR the boot. “We basically said that KBR is too big to fail,” commission co-chair and former Rep. Christopher Shays (R-Conn.) complained last year, “so we are still going to fund them.”