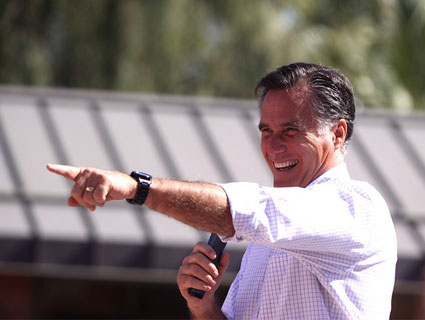

Mitt Romney at the NAACP.

Mitt Romney’s speech to the NAACP Wednesday didn’t go spectacularly well. Although he received a largely cordial reception, he was booed when he promised to repeal Barack Obama’s signature domestic accomplishment, the Affordable Care Act.

Some analysts have suggested the boos may help Romney by making him look magnanimous and showing that he’s willing to appear before an unfriendly audience to make his pitch. It’s doubtful, given Romney’s reaction and the campaign’s decision to send out a version of the video with the boos edited out, that getting booed was part of Romney’s plan. Nevertheless, the Romney campaign is likely to use the boos to its advantage going forward. Conservative pundits, already wary of at the NAACP for previous slights, will foment outrage on his behalf. Politically, it’s hard to see how the appearance hurt Romney, or how it could have—so it’s overstated as an example of political valor.

There are substantive reasons why Romney’s pitch fell flat. Romney told the NAACP that “I believe that if you understood who I truly am in my heart, and if it were possible to fully communicate what I believe is in the real, enduring best interest of African American families, you would vote for me for president.” This is a spectacularly bad pitch for any politician, because it happens to matter very little what candidates feel in their heart. What matters is the party they represent, and the policies they’ve committed to pursuing.

The economic crisis has lead to a collapse of minority wealth, and black Americans continue to have a higher unemployment rate than whites. But even here, the GOP’s message to black voters is hampered by the false Republican narrative that laws banning discrimination in lending led to the crisis, and, as Slate‘s Dave Weigel points out, a Republican-backed policy of austerity has disproportionately affected black people, who are more likely to work for the government. The audience at the NAACP is not going to take kindly to the suggestion that lending institutions need more leeway to shovel out “ghetto loans” to minorities. Nor are they likely to appreciate the argument that friends and family members deserved to lose jobs that could have been easily preserved by policies past Republican presidents have used but the GOP blocked when Obama proposed them.

The unpleasant reception to Romney’s reiteration of his promise to repeal the federal health care legislation modeled on his own reforms in Massachusetts likely goes beyond a dispute about policy. Romney said prior to the Supreme Court ruling upholding most of the Affordable Care Act that if the high court overturned the law Obama’s first and possibly only term would have been “wasted.” By promising to repeal the Affordable Care Act, Romney was reminding the NAACP that he is running on a promise to erase the term of the first black president as though it never happened.

During her controversial routine at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner in 2009, comedian Wanda Sykes joked that “You’re proud to be able to say that, The First Black President. That’s unless you screw up. Then it’s going to be, ‘What’s up with the half-white guy, huh? Who voted for the mulatto, what the hell?'” Part of the joke is that despite racial progress in the US, the black community will be collectively affected by whether history judges Obama’s presidency as a success or failure. Even those NAACP members more favorably disposed to Republican ideas may feel the same way. That is why Romney’s pledge to wipe the Obama administration from history has an unpleasant resonance for many black voters, even beyond the community’s decades-long allegiance to the Democratic Party.