We don’t know how many civilians are killed in drone strikes, but we do know the US government is almost certainly wrong about it.

That’s one conclusion you could draw from a report on the impact of the use of drones in targeted killing by the the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict*, released Sunday, a year to the day that radical American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki was killed in a drone strike in Yemen. While the US government has maintained that few if any non-militants are killed in drone strikes, reports about how targeting decisions are made, the realities of airborne warfare, and the basic fallibility of humankind call the Obama administration’s claims of precision into question. There’s also the problem that some behaviors which might seem to indicate “guilt” out of context, like carrying a gun, are common in the areas being targeted. “A civilian carrying a gun, which is a cultural norm in parts of Pakistan, does not know if such behavior will get him killed by a drone,” the report notes. While “personality” strikes are aimed at specific individuals, the government also conducts “signature strikes” which hit anonymous individuals on the basis of a “pattern of behavior.”

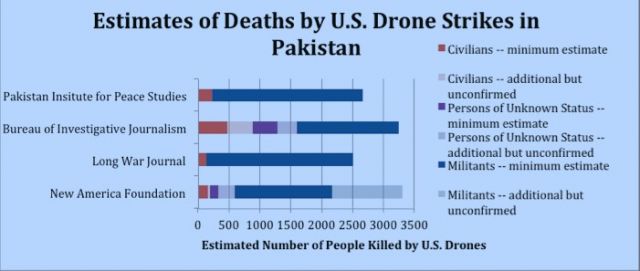

Because the government has yet to even officially acknowledge the existence of the CIA’s targeted killing program or its military counterpart in the Joint Special Operations Command however, it’s hard to evaluate the Obama administration’s claims about avoiding civilian harm. The report notes that the dearth of first-hand information from the areas most frequently targeted by drone strikes means that determining who is a “militant” and who is not, particularly after the fact, is very difficult. That’s why third-party estimates, which cast serious doubt on the government’s assessments, vary so widely, and why the Obama administration itself may not even know how many civilians are being killed. Here’s a chart from the report:

The report points out that the impact of drone attacks on civilians cannot be measured by deaths alone. “[O]ne civilian death or injury is enough to dramatically alter families’ lives. In Pakistan, families are often large, and their well being is intricately connected among many members. The death of one member can create long-lasting instability, particularly if a breadwinner is killed.” Even if no civilians are killed, the report states that property damage related to strikes can drastically alter the lives of those impacted. “A house is often a family’s greatest financial asset. In northern Pakistan, homes are often shared by multiple families, compounding the suffering and hardship caused when a house is destroyed.” That’s to say nothing of the psychological effects of living in a place where you never know if fire will rain down from the skies. The study quotes Michael Kugelman of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, who says that “I have heard Pakistanis speak about children in the tribal areas who become hysterical when they hear the characteristic buzz of a drone.”

The report recommends that the Obama administration empanel an “interagency task force” to “evaluate covert drone operations” with regard to civilian harm, oversight, and accountability. The ongoing popularity of drones as a method of fighting terrorism without putting American lives at risk, however, gives the administration little political incentive to publicly reevaluate its drone policy, despite the fact that its being shrouded in secrecy denies Americans the ability to make informed value judgements about whether it does more harm than good—or even how much harm or good they actually do.

*An earlier version of this post mistakenly referred to the producers of the report as the Center for Civilians in Conflict at Columbia University.