YouTube

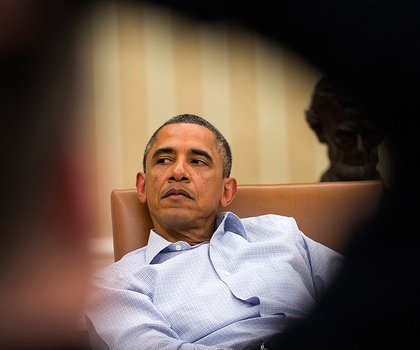

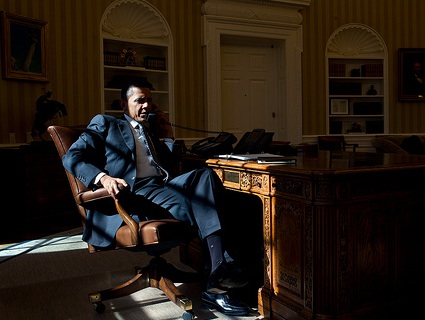

During a Google+ “Fireside Hangout” Thursday evening, President Barack Obama was asked if he believed he has the authority to authorize a drone strike against an American citizen on US soil.

He didn’t exactly answer the question.

The Council on Foreign Relations’ Micah Zenko transcribed the whole exchange. Lee Doren, a conservative activist, asked the question; here’s Obama’s answer:

First of all, I think, there’s never been a drone used on an American citizen on American soil. And, you know, we respect and have a whole bunch of safeguards in terms of how we conduct counterterrorism operations outside the United States. The rules outside the United States are going to be different then the rules inside the United States. In part because our capacity to, for example, to capture a terrorist inside the United States are very different then in the foothills or mountains of Afghanistan or Pakistan.

But what I think is absolutely true is that it is not sufficient for citizens to just take my word for it that we are doing the right thing. I am the head of the executive branch. And what we’ve done so far is to try to work with Congress on oversight issues. But part of what I am going to have to work with congress on is to make sure that whatever it is we’re providing congress, that we have mechanisms to also make sure that the public understands what’s going on, what the constraints are, what the legal parameters are. And that is something that I take very seriously. I am not someone who believes that the president has the authority to do whatever he wants, or whatever she wants, whenever they want, just under the guise of counterterrorism. There have to be legal checks and balances on it.

Doren isn’t the only one who wants an answer to this question. Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky.) has placed a hold on John Brennan, Obama’s nominee for CIA director, “until [Brennan] answers the question of whether or not the President can kill American citizens through the drone strike program on U.S. soil.” Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) posed that exact question to Brennan in a written questionnaire, but his answer was as opaque as Obama’s. “This Administration has not carried out drone strikes inside the United States and has no intention of doing so,” Brennan wrote.

So why didn’t Obama just say, “no, the president cannot deploy drone strikes against US citizens on American soil”? Because the answer is probably “yes.” That may not be as apocalyptically sinister as it sounds.

“Certainly, we routinely ‘targeted’ U.S. citizens during the Civil War,” says Steve Vladeck, a law professor at American University’s Washington College of Law. “Even if the targeting was with imprecise 19th-century artillery as opposed to 21st-century [unmanned arial vehicles].” If he had the technology, President Abraham Lincoln would most likely have been within his authority to send a drone to vaporize Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

Drone strikes in the modern context, however, aren’t being used against uniformed commanders of a traditional military force. Instead, we’re talking about strikes that target individuals suspected of being part of terrorist organizations where “membership” is an inherently more nebulous concept.

There are two government agencies known to conduct drone strikes, the CIA and the Department of Defense. CIA involvement in a domestic drone strike is probably off-limits, says Paul Pillar, a former CIA official who is now a professor at Georgetown University. The idea is really far-fetched anyway, Pillar argues. “I expect that if the CIA were to do anything like that within the U.S. it probably would violate some of the legal restrictions that are placed on all of the agency’s activities as far as inside-U.S. operations are concerned,” Pillar wrote in an email to Mother Jones. “Nothing like this is ever going to arise as far as drone strikes are concerned, so I don’t see it as a live issue.”

Since the CIA is probably out, that leaves the military. Congress has long held that the president has the authority to use the military domestically in some circumstances. The Posse Comitatus Act, passed after Reconstruction to limit the use of military force on US soil, states that the military can be used to enforce the law “in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress.” The last time this happened was 1992 when, citing the Insurrection Act, President George H.W. Bush called out the National Guard to suppress the Los Angeles riots in the aftermath of the Rodney King verdict.

According to US law, Congress can authorize the use of the military inside the US. The question is whether the Authorization for Use of Military Force, which Congress passed in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, counts as “express authorization” to carry out a targeted killing on US soil. The Obama administration stated in its white paper explaining its legal authority to kill US citizens abroad that capturing a suspected terrorist should be “infeasible” before a strike is authorized. But “the government’s going to have a devil of a time proving that capture is infeasible for any individual found within the territorial United States,” Vladeck says. And there’s no reason to believe that local or state authorities, or if necessary the FBI, wouldn’t be left to handle a situation involving suspected terrorists. (Local police dropped a bomb during an armed standoff with the radical group MOVE in Philadelphia in 1985, proving that civilian authorities can be just as lethal as the military.)

The law says military force can sometimes be used against people on American soil, such as if it were needed to fight an armed domestic insurgency. But we still don’t know how broad the Obama administration thinks that authority is. Less than a week before President George W. Bush left office, the Justice Department withdrew a series of memos written by torture memo author John Yoo that envisioned near-dictatorial authority for the president, including the authority to deploy military force against terrorism suspects inside the US. Yoo had basically given Bush the executive branch equivalent of the Konami Code.

The Bush Justice Department argued that Yoo’s theories should no longer “be treated as authoritative for any purpose.” The question is whether the Obama administration has envisioned similar authority for itself. The answer to that question lies in the classified documents explaining the Obama administration’s legal rationale for the targeted killing program—documents that the Obama administration has so far refused to fully disclose to Congress, let alone release to the public.