Photo: David Bowman

i first met my daughter in the lobby of the Westin Camino Real, the grandest hotel in Guatemala City. The night before, my husband Walter and I had soothed our nerves running on the treadmills in the fitness center, where a polite attendant handed us plush white towels and spritzed the equipment with a flowery disinfectant. Afterward I wrote a series of letters to our daughter. Because children adopted from overseas usually have little information about their history, parents are advised to document the trip as best they can, creating what is known as an “adoption story.”

Reading the journal now, more than two years later, it feels so self-conscious. “We’ve been waiting so long to meet you—almost seven months!” the first entry reads. “Ever since you were seven days old and the agency emailed us your beautiful photos, we’ve wondered what you will be like. We fell in love with you that minute!” Gone is any sense of the surreal. Walter and I already had two biological sons; now we were jetting into a Third World country with the sole aim of leaving with one of its daughters. (Wanting a girl, we’d opted for the sure bet that adoption offers.) I mentioned, but didn’t dwell on, the brutal poverty outside our hotel windows, focusing instead on how my sons were looking forward to meeting their little sister.

There is one section of the journal, however, that jumps out from the boilerplate. “I feel so sad for the pain your birth mother must be in since she is not able to raise you,” I wrote. “But I believe now that I am your ‘real’ mommy.” Reading those words now sparks a flash of shame. Because even though my daughter was, as is required by U.S. immigration law, legally classified as an orphan, she had two Guatemalan parents who were very much alive.

I remember being comforted by the Guatemalan social worker’s report on the case; the baby’s mother, Beatriz,* had evidently made an informed choice to place her for adoption. Or at least that’s what I told myself.

The truth is that I didn’t know Beatriz. And I was secretly relieved this was so.

people have been parenting children not born to them since the dawn of time. But adoption as an irrevocable severing of a child’s relationship with her biological family is largely a European and American practice. “In the vast majority of the countries where children are adopted from, the Western notion of adoption doesn’t even exist,” says Hollee McGinnis, policy and operations director of the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, a research and advocacy organization. “Informal adoption and kinship care have always existed, but our form of formalized adoption by nonrelatives is very, very new.”

Until 1945 (and in some states much later), most adopted Americans and their parents had legal access to birth certificates and related court documents. Adoption agencies even facilitated contact between adoptees and birth relatives. The push toward secrecy and sealed records took hold in the postwar culture, when adoptions were increasingly run by social workers. Confidentiality was thought to shield both mothers and children from the stigma of illegitimacy, and it allowed parents to hide their infertility even from their own children—birth certificates were simply changed to list the adoptive parents. (This practice continues today. My daughter’s American birth certificate lists her birthplace as Antigua, Guatemala, but gives us credit for the one thing we most certainly did not do.) Young pregnant women were rushed into homes for unwed mothers, where social workers told them they’d forget about their babies once they signed the adoption papers.

But they didn’t. In the 1970s, a psychology professor named Lee Campbell realized that she was suffering from mental health problems brought on by being forced to “surrender” her infant son when she was a high school senior in 1962. Campbell wrote a letter to the Boston Globe in 1975 asking what were then called biological mothers to contact her if they were interested in talking about their experiences.

These women founded Concerned United Birthparents, one of a handful of organizations that advocate for birth families. (The use of the term “birth parent,” coined by Campbell, is controversial. Some parents believe it relegates them to breeder status; alternate terms include “natural parents,” “first parents,” “surrendering parents,” or simply “parents.” I call Beatriz my daughter’s “Guatemalan mother” because it feels somehow more factual, although to be honest I have never referred to myself as her “American mother.”)

As more women gained access to contraceptives and legal abortion, and the stigma of unwed pregnancy lessened, fewer American women placed their babies for adoption, and those who did had more power to get what they wanted, including knowing their children’s fate. Today, almost no American woman deciding on adoption seeks anonymity; roughly 90 percent of mothers have met their children’s adoptive parents, and most helped choose them. Research shows that such arrangements result in less grief for the birth parents and many benefits for adoptees.

Yet the vast majority of transnational (also called international and intercountry) adoptions remain closed—and it’s widely understood that this appeals to some adoptive parents. “It’s about entitlement and ownership,” says Marley Greiner, the executive chair of the activist adoptee group Bastard Nation. “When you read the adoption boards online, it seems like parents go overseas because they don’t want some pesky birth mother or relative showing up.”

In fact, while we’ve belatedly acknowledged the trauma of American women who were forced to surrender their children, birth families abroad have remained shrouded in mystery, allowing parents and professionals to invent the narrative that best suits them. “Practitioners 20 years ago assumed we were rescued from these horrific nations and would never go back,” says McGinnis, who was adopted from Korea when she was three and has been in touch with her Korean family for more than a decade. And while many adoptees won’t want to meet their birth families, she notes, virtually all would like basic information about their background. “We grow up in environments where it is so much about your dna, it’s quite natural for adopted people to feel excluded because we don’t have that basic human right.”

The right to background information is laid out in a little-noticed provision in the 1993 Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption, which 74 countries have signed. If the U.S. Senate finally ratifies the treaty this winter, as expected, the transnational adoption landscape may change. Already, Children’s Home Society and Family Services of Minnesota, one of America’s most prominent adoption agencies, has shifted to advocating openness and helps with birth family searches in Guatemala, Korea, Colombia, and Peru.

Still, the treaty’s provisions are nonbinding, and parents who prefer closed adoptions will be able to arrange for one. And while celebrities’ forays into transnational adoptions bring on the occasional ethics complaint, there’s no sign of a broader debate. “It’s absurd on some level,” says open-adoption pioneer Campbell. “Every day, parents look into the face of their child and they see a different race and a different ethnicity. And yet, they compartmentalize that truth and deem it unimportant. Why aren’t the movie stars talking about the birth parents of their kids and modeling the opportunity to do it right?”

walter and i had tried to do everything right. We’d heard of corrupt adoption lawyers, fly-by-night operators who use online photo listings to lure parents, of baby stealing and baby selling, and of the myriad agencies that offer, for hefty fees, to help Americans bring home a child from some of the world’s poorest countries. We chose one of the largest and most respected, and faithfully attended all the counseling appointments it offered, including a seminar that featured a session with an American birth mother. She clearly loved her son, but said she hadn’t been ready to become a mother. “I’m not his parent,” she told us.

And yet when it came time to choose a program, our agency told us to go with whatever we were comfortable with, as if “open” and “closed” were items on a menu. We asked our social worker about a domestic open adoption; she said that because we already had biological children and were only open to adopting a girl, we wouldn’t be a very compelling family to an American birth mother. We never discussed adopting from the U.S. foster care system or an Eastern European orphanage; we wanted a baby who had never spent an hour in institutionalized care. We also wanted our daughter’s country of origin to be easy to travel to, so we could go there for family vacations. Talk about menu items!

We did agonize over some moral questions—the potential hardships for a Latina child raised in a white family, the ethics of choosing the sex of our child. At every step, we were reassured that what we were doing was a good and worthy thing. “I think [adoption] is almost an antithesis to oppression,” Kevin Kreutner, a moderator at the support group Guatadopt.com who is in contact with his children’s Guatemalan family, told me. “For people who are given no access to family planning, have an unplanned pregnancy, and can’t raise that child, there is a liberating sense where they can realize that this child will not suffer that same oppression.”

“I just need to know that the child we adopt has no other options,” Walter finally told our social worker. I can’t remember her exact answer, but it was something along the lines of “all these children need families.” When I later told this to an adoptee-rights advocate, she said the agency should have pursued a discussion that might have dissuaded us from transnational adoption, or led us to a program through which we could sponsor a child to remain with her family. But the truth is I don’t think I would have listened—so absorbed was I in the force of my own wanting.

when we got our daughter’s paperwork, Walter and I noticed that her first, middle, and last names were exactly the same as her mother’s. We told ourselves this was probably because the adoption lawyer had suggested it—an efficient decision made for the sake of checkups and court appearances. I’d read that some adoptees believe their given name is a precious connection to their heritage. When we asked our social worker what she thought about changing it, she said it was up to us to decide what was right for our family. So we changed her first name to Flora and made Beatriz her middle name.

We did not, however, want Flora’s life before us to be irretrievable, so we asked if Beatriz wanted to meet us and stay in touch. Our social worker contacted the lawyer in Guatemala, who replied that Beatriz “would love to know us.” Then, a week before our trip, the social worker called and said there would be no meeting; Beatriz had gone back to her village and wasn’t reachable.

“But she’s from Guatemala City,” I said. “Do you think the lawyer is telling us the truth?” The social worker said it was hard to know. Adoptions in Guatemala are arranged entirely by private lawyers, without oversight from any central authority, and corruption is widespread. Our agency promised it carefully screened those it worked with in Guatemala. But this incident gave us pause. The lawyer might technically be representing both Flora and us, but whose interests was he really looking out for?

a week later, we flew to Guatemala City. The hotel of choice for American adoptive parents is the Marriott, which is so used to these “pickup” trips, it offers strollers for rent and has arranged with a nearby pharmacy to deliver formula and diapers to panicky new parents. Via chat rooms, adoptive parents with similar pick-up trip schedules make arrangements to connect at the Marriott. But the idea of all that camaraderie just heightened my anxiety. So we stayed at the Westin.

As the elevator chugged down toward the lobby, Walter pointed the video camera at me and said, “Here’s Mommy waiting to see Flora for the first time!” I forced a feeble smile. I was naked and sweating when I met my sons in the sterile glow of a hospital birthing room. Now I stepped out onto rose-marble floors to face Flora’s foster mother Maria, a stout woman with a six-month-old girl riding at her hip in a woven sling. As they cuddled and laughed—later I’d look at photos of this moment to remind myself that Flora could laugh; for weeks her eyes grazed her new home with a dull blankness—my heart sank.

Our lawyer was, to our surprise, not present. My limited Spanish had drained from my memory, but somehow I managed to ask Maria to walk with us to the hotel’s business center so that we could hire a translator. On our way, a gray-haired man in a suit stopped to shake Maria’s hand. Later she told me he was an adoption lawyer; he owed her four months’ salary that she knew would never be paid.

The woman who ran the business center was feeding documents into a fax machine when we blew into her office. On seeing Flora, she rose and shook hands with Walter and me. Then she nodded at Maria. I told her I needed to ask Maria a few questions: What time did Flora go to bed? How often did she nap? Did she eat solid foods?

A Star Is Adopted

In the 1950s, celebrity parents such as George Burns and Gracie Allen gave adoption mainstream cachet; now Brangelina et al launch new adoption trends, and controversies, each time they bring home another child.

—Ellen Charles

|

adopted from |

aftermath |

candidate for sainthood? |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Angelina Jolie |

Cambodia (Maddox, 2002), Ethiopia (Zahara, 2005), Vietnam (Pax, 2007) |

A month after Jolie filed Maddox’s adoption papers, the ins suspended adoptions from Cambodia because of fraud and baby stealing; no foul play was found in her case. When she brought home Zahara in ’05, Jimmy Kimmel sniped that she and Brad Pitt were just deflecting attention from breaking Jennifer Aniston’s heart. |

Pitt has said he’s ready for No. 5; he and Jolie have reportedly been looking at Chad and the Czech Republic. |

|

Meg Ryan |

China (Daisy True, 2006) |

This year China disqualified single parents such as Ryan and required adoption applicants to vouch that they are not gay or lesbian. |

“I just really wanted a baby. I was on a mission to connect with somebody.” |

|

Mia Farrow |

China, India, South Korea, Vietnam (10 children, 1973-1995) |

Woody Allen, Farrow’s companion of 12 years, married her adopted daughter Soon Yi Previn in 1997. Previn and Allen have adopted two children, Bechet (China, 1999) and Manzie (Texas, 2000). |

“I felt that I had a lifeboat and that many people were drowning all around the world. I could take some into my lifeboat.” |

|

Madonna |

Malawi (David, 2006) |

Madonna picked 13-month-old David from an orphanage even though he had a father who rode his bike 50 miles twice a week to visit him. After the adoption, the father said he hadn’t wanted to give David up. The Malawian government brushed him off. |

“I have the welfare of all of you at heart and I love you,” the Material Girl told a group of orphans in Malawi. “I will try to support you all and take care of you in the same manner as David.” |

She dutifully repeated my questions, but after Maria answered, she paused.

“She wasn’t told that this was your pickup trip,” the translator told us. “She thought you were only visiting.”

Tears streaked down Maria’s cheeks as she adjusted the stroller’s back to show us that Flora liked to take her bottle lying on her back. Then, her voice catching, she recited the prayer Flora fell asleep to every night, crossing herself as she whispered. She explained that she and her husband tried to prepare themselves to say goodbye, but it was always hard. We asked her to join us for lunch in our room and she stayed until eight that evening; I’m still not sure how we found the words and gestures to communicate.

When I asked Maria if she knew Beatriz, she smiled. “Muy linda,” she said. “Muy cariñosa.” Very lovely. Very affectionate. That last word opened up a hopeful possibility: Had Beatriz been able to spend time with Flora? The agency hadn’t been able to tell us, and the lawyer’s office claimed Beatriz didn’t have a phone.

Maria looked puzzled when I told her this. Then she held up her cell phone and gestured that Beatriz’s number was stored in her speed dial.

“Would she want to meet us?” I asked.

Maria shook her head. I think she said that it would be too painful for Beatriz.

I looked at Flora gumming a french fry. Maria had styled her hair so that two tiny ponytails stuck out atop her head like miniature oil geysers. Somewhere, a woman was coming to terms with the fact that she would never see her baby again.

maria called on Flora’s first birthday to say that Beatriz wanted us to know she felt she had made the right decision. A few weeks later, our social worker told us that Beatriz had visited the lawyer and wanted to see photos of her daughter.

Several months later, Maria called again. The lawyer had threatened to fire her if she continued to contact us.

That night I was changing Flora’s diaper. “Who’s my girl?” I sang as I pulled the tab taut across her stomach. She pointed at her chest and laughed, her dimples creasing into pinholes. Then she reached up to tickle my chin. “Flora Beatriz,” I cooed. “You are one beautiful kid.” Hearing myself say her middle name took me aback. Beatriz, I suddenly realized, had chosen it, the only connection to their brief life together.

And that’s when it finally sank in: Beatriz hadn’t made a “choice” in the liberating way that our post-Roe culture thinks about reproductive options. Like any woman in the developing world placing a child for adoption, she’d buckled under crushing financial or social pressure—perhaps even coercion. I’d considered this before, but had always batted the thought away by telling myself that Flora was going to be adopted, whether it was we who stepped forward or someone else.

Walter walked in, flushed and sweating from wrestling with the boys, who were now happily digging into bowls of applesauce.

“She’s getting so big,” he said. “She’ll be talking soon.”

His smile fell as he saw me crying. “Did something happen today?”

I nodded.

“I think Beatriz wants us to find her,” was all I could say.

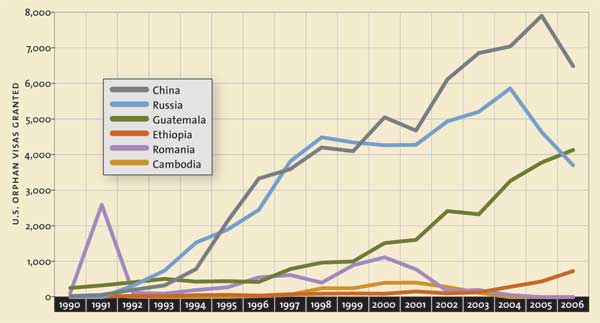

is it ethical for an adoptive parent to push for information about her child’s birth family? Or should that be a decision left to the adoptee? And what about the birth family’s right to privacy? “You can’t compare an open adoption in the U.S. with an open adoption process internationally,” says Susan Soon keum Cox, vice president of public policy at Holt International, an Oregon adoption agency whose founders launched transnational adoptions in the United States. The child of a Korean woman and a British soldier, Cox, who was adopted in 1956, found her Korean half brothers when she was an adult. Yet she cautions against too-hasty birth family searches. “The stigma of adoption in many countries is still very powerful and very real. Women place their children for adoption and slip back into society. It’s a very different thing than the acceptance of single parents and adoption in the U.S.” In China, currently the greatest source of transnational adoptees—6,493 U.S. “orphan” visas were issued to Chinese adoptees in 2006—relinquishing a child is illegal, and families sometimes abandon their children to avoid running afoul of the one-child policy; birth mothers found to have done this can face prosecution.

While there is no simple way to track down Chinese birth families right now, voluntary dna data banks might one day help people find relatives. (A database developed by the University of California-Berkeley’s Human Rights Center is already connecting children stolen during El Salvador’s civil war with their families.) “China will be a different China in 10 years,” says McGinnis. “Just as Korea is not the same Korea it was in the 1970s.” A Dutch family recently traveled to the Chinese town where their daughter was born; they talked to the media, a couple came forward, and dna tests confirmed that they were the girl’s parents.

Some of these reunions could turn out to be unsettling. “One of the ways that wrongdoers hide their child-laundering schemes is by the closed-adoption system,” says David Smolin, a law professor who’s written extensively on corruption in transnational adoption. He and his wife adopted two sisters from India only to find out that they had been stolen from their birth family. Last March, a Utah adoption agency was indicted in an alleged fraud scheme involving 81 Samoan children whose parents were told that they were sending their children away to take advantage of opportunities in the United States—that there would be letters, photos, and visits, and that the children would return when they turned 18.

Openness, Smolin notes, would also make it harder for parents to think of adoptions as “rescuing” children. “There are cultural reasons why people give up children for adoption,” he says. “But when you have a situation where money alone, in relatively small quantities, would allow the birth family to keep the child—under current law you are allowed to take the child and spend $30,000 when $200 would be enough to avoid the relinquishment.”

As it stands, families who have forged relationships with birth parents often find it impossible to turn their backs on their economic needs. Some send a monthly stipend; others pay for the education of their child’s siblings, help finance businesses, or buy computers or cell phones to make it easier to stay in touch. And while all this is legal once the adoption is finalized, it’s a lot messier than writing a check for Save the Children. “We need to be careful what kind of impression that makes with other people in the village or area,” says Linh Song, the president of Ethica, a nonprofit organization that advocates for transparent adoptions worldwide. “Will they receive aid if their child is sent abroad?”

i was working on deadline the afternoon Susi’s email flashed on my screen, a month after we had hired her to find Beatriz. Operating by word of mouth, Susi has done hundreds of searches for birth families in Guatemala and elsewhere in Central America. In 1999, when she first considered this line of work, “I asked my friends and they all said, ‘No, don’t get involved in that.’ People here see adoptions only as a business. A big business. And when there is a lot of money involved, there is corruption.”

Still, the idea of connecting families appealed to her. Her first search was easy. “I knocked on the door of the address I was given by the adoptive family and the birth mother opened the door.” Soon, though, she got threats: Stop, or you’ll get into trouble. Her husband accompanies her on every search; she will not contact anyone who works directly with adoptions, or discuss the details of a search.

Her email relieved us of two worries: Beatriz had been hoping we would find her, and she had not been coerced into placing Flora for adoption. She thanked us for making it possible to watch her child grow up. She missed her, prayed for her, and wanted Flora to know that not a day passed when she didn’t think about her. She said that before the adoption she was a bubbly person. Now she kept mostly to herself.

I’d nurtured a vague notion of a faraway woman grieving for her lost child. But as soon as an image of Beatriz sobbing into her pillow materialized, my brain concocted a counter-narrative, a story in which she was healing from her loss. A story in which not having to raise the child I tucked into bed every night freed Beatriz in some way.

Then one evening not long after the email arrived, Walter and I spent our date night at a reading of Outsiders Within: Writing on Transracial Adoption, an anthology that is a stirring and stern rebuke to the standard heartwarming adoption narrative. Back in our car, Walter bowed his head.

“We should give her back,” he said.

I’d harbored the same thought, but the anguish on his face threatened me enough to push back.

“We can’t,” I answered.

“Why not?” he countered. “It wouldn’t take much money to support them.”

“Because we are her family.”

“She’d adjust.”

“How do you know that?” It was an unconvincing dodge. We were friends with several families who had adopted toddlers; their kids were thriving. “How could we do that to the boys?” I insisted.

“We couldn’t,” Walter said.

“And how could we do that to us? I couldn’t live with that pain.”

“But why should Beatriz have to?” he asked.

To most Americans, Flora’s adoption is measured entirely by what she gains—Montessori schools, soccer camps, piano lessons, college. But it no longer quite computes that way for me. To gain a family, my daughter had to lose a family. To become an American child, she had to stop being a Guatemalan child.

McGinnis told me that because adoptive parents are put through such a rigmarole of assessments and trainings, it’s easy for them to jump on the “super-parent track” in the quest to raise a happy child. “If ‘adoptees want to know their past’ becomes another item on the super-parent track, it’s important to understand whether you are doing a search because you don’t want your child to be mad at you later,” she says. “My research has shown what makes a healthy identity is when the adopted person feels like they have a chance to make decisions.”

Walter and I are nothing if not grade-grubbing students in the super-parent classroom. We have a babysitter who is from Guatemala and speaks only Spanish with our children. She cooks us pepian and invites us for tamales with her family, which likes my trés leches cake. A jade statue of a Mayan corn goddess stands on our living room shelf, and a woven huipil hangs in the hall. We send the boys to a summer camp for children adopted from Latin America and their siblings, and get together once a month with other families with Guatemalan children. From the moment we met Flora, we planned on visiting Guatemala every few years.

Which is all very well—but the results can sometimes feel like a trip to Epcot. Perhaps one day Flora will appreciate our efforts; maybe she will resent them. I hope that if she rolls her eyes at our jaguar masks and woven placemats, I’ll be able to smile. But what if the decision she most resents is the one we can’t rescind? You can’t exactly put a birth family back into a drawer.

by the time we returned to Guatemala City, Flora was two and a half. Walter and I had decided it would be easier for her to meet Beatriz this young; as she grew up, she and Beatriz would figure out what they wanted from their relationship. But it was an uneasy compromise. Unlike our domestic counterparts, we didn’t have the benefit of longitudinal studies and books detailing best practices. We didn’t even really have an open adoption. There was no legal document to set out the terms of contact, only a tendril of trust spun from the fact that Beatriz, Walter, and I all loved the same child.

Where Do Babies Come From?

|

CHINA Greater wealth and a looser one-child policy have shrunk supply of adoptable babies; this year, China banned parents who are unmarried, obese, over 50, taking psychotropic drugs, or are worth less than $80,000. RUSSIA Popular, though expensive (up to $30,000), destination for parents. But Moscow tightened rules after an American adoptive mother was convicted of killing her Russian-born son in 2005. |

GUATEMALA Very young infants can be adopted; single women as well as couples with one partner over 50 may adopt. But State Department warnings about fraud and baby smuggling may slow the flow. ETHIOPIA Has been rising in popularity thanks to model orphanages and an efficient adoption system—but may not be able to handle the surge in applications that followed Angelina Jolie’s adoption of Zahara in 2005. |

ROMANIA Foreign adoptions shot up after Romania’s packed, miserable orphanages made world headlines following dictator Nicolae Ceausescu’s fall; protests ensued, and Romania froze adoptions the next year. Some U.S. parents, unable to cope with children who had massive mental health problems, placed kids in foster care. CAMBODIA In 2001, State Department issued first-ever ban on adoptions from an entire country, citing corruption and outright baby selling. |

The day before we met Beatriz, I asked Susi what it was like for Guatemalan mothers to see their child with another set of parents.

“I think it gives them peace,” she replied. “They feel, ‘I am dark-skinned. I am a woman. I have no education. I gave him away. I am worthless.’ They think about this child every day, but they feel like they have no right to that child. [After a reunion], they understand that they are being given the opportunity to have a relationship and that they deserve it.”

And what about the adoptees? “The most important thing for the adopted child is to know that they weren’t given up because they weren’t loved,” she said. “It is so obvious to me that they are deeply, deeply loved by their birth mothers.”

Susi had decided we should meet Beatriz at McDonald’s because it would afford us some anonymity. It turned out to be the perfect setting for Flora, no stranger to the pleasures of McNuggets and giant sliding tubes. In the lunchtime rush, few looked up from their Big Macs to wonder why a blond gringa and a petite Guatemalan were clinging to each other and weeping.

When you meet your daughter’s mother, you don’t waste time with small talk. And at first, there was no need for talking because Beatriz could not take her eyes off Flora.

“Hola, mi amor,” she said as she bent down.

Flora frowned and turned away. “I want Daddy,” she said.

Walter picked her up and kissed her cheek. “Sweetie,” he said. “This is Beatriz. She’s your Guatemalan mommy.” Flora buried her face in his shoulder. Nervously, we tried to draw her out. But Beatriz told us not to worry.

With Susi translating, Beatriz told us that she was deeply depressed for a year after the adoption was finalized. She got through her pain by turning to God. She loved being in the hospital with Flora and demanded as a condition of the adoption that she could visit her in foster care. She assumed that she would never see Flora again and she was still in shock that she had. She took obvious delight in how healthy and happy Flora was. She told us the names of all of Flora’s relatives and explained that Flora gets her dimples from her uncle.

Somewhere along the way Flora smiled at Beatriz and lobbed a Happy Meal Furby toy onto the table. Beatriz laughed.

“She’s kind of a tomboy,” I said.

Susi and Beatriz looked puzzled.

“She likes to play boy games with her brothers,” I continued. Flora was dressed for the occasion in a freshly ironed dress and white patent-leather sandals; I’d even had her ears pierced so she would look like other Guatemalan girls.

“She doesn’t like dresses,” I continued. “She prefers pants.”

“Oh!” Beatriz clapped. “Just like me!”

“And she is very attached to Walter.”

“That’s just like me, too!” she continued. “I loved my father more than anyone.”

As if on cue, Flora pooped and would only allow Walter to change her diaper. As he grabbed the wipes and trudged off to the men’s room, Beatriz and Susi looked at each other. “We train the men differently in the United States,” I said.

“Obviously,” Beatriz laughed.

Then I blurted it out, sobbing. “I’m sorry we changed her name.”

“Don’t worry,” Beatriz said. “You’ve given me more than I could ever have imagined.” Her gratitude was unsettling, unnecessary, overwhelming.

Many adoptive parents describe their connection with their children as something that was destined by a larger force. “God brought us to each other,” they’ll say. “We were meant to be a family.” I understand why we want to think that, but the reality is, Flora is my child because something went wrong. To believe otherwise would mean that God intended for Beatriz to suffer because she couldn’t afford to raise her child, that we were meant to have the option of adding a girl to our family because we could afford the price.

At the end of our third hour together, all of us—save Flora—looked shell shocked, but no one wanted to leave. Beatriz asked if I worked. I said I was a journalist and that one day I hoped to write about women in Guatemala and other countries who place their children for adoption. I told her that we don’t hear much about these mothers.

Beatriz nodded. “Please write about me,” she said. “Please tell the Americans how much I love my daughter.”

so what will Flora make of that day, much less this article? I have no idea. But I think a lot about what Hollee McGinnis told me about her Korean family. “Adoptees have to ultimately figure out what it means that they were adopted,” she said. “Yes, they can go and ask some questions, but the meaning-making will be theirs. Openness is really good in that you don’t have to jump through all these extra hurdles. But the work of figuring it out is still there.”

Loving an adopted child is easy. In fact, Flora’s adoption was in some astonishing way more powerful than giving birth to my sons. To fall so deeply for a daughter who has no genetic link to me made me realize that we are simply hardwired to love the children we are given to raise.

Raising an adopted child is, however, a complicated privilege. Walter and I could not turn our backs on Beatriz’s poverty. After trying unsuccessfully to find a nonprofit that would help us sponsor her somehow, we finally decided to just send her money through Susi so she could finish her education. Could this encourage women in her neighborhood to place a child for adoption? Could we possibly not do it?

What I do know is that I have never felt more like Flora’s “real” mother than when Beatriz and I were holding each other next to Ronald McDonald. And that’s not because Flora so obviously saw me as her mommy. It’s because I now understand I’m not her only one.