Photo: Henning Schacht/Action Press/ZUMA Press

IT WAS LATE September 2002, and construction crews were just finishing work on the main prison camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, when three German intelligence agents arrived on the island aboard a U.S. military plane.

The reason for their visit was sensitive. The Pentagon was still arguing that those held at Guantanamo were “the worst of the worst” and “the most dangerous, best-trained, vicious killers on the face of the Earth,” but behind closed doors CIA officials were coming to the conclusion that a number of detainees had no links to terrorism, and were working on a list of prisoners to be set free.

One of the detainees being considered for release was Murat Kurnaz, a German-born Turkish citizen who had been pulled off a bus in Pakistan the year before and turned over to U.S. forces. Since then, American security agencies hadn’t turned up any evidence that he belonged to a terrorist group or posed a threat to the United States. But before clearing his release, the CIA wanted the Germans to interrogate him and offer their stamp of approval.

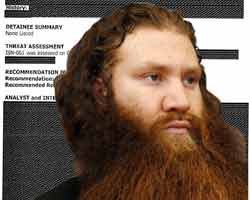

Shortly after they arrived, the agents were led out to a trailer near the dusty sprawl of cell blocks known as Camp Delta. The air conditioner was on full blast, and Kurnaz, a stocky young man with blunt features and a thick red beard, was seated on one side of a long table, his hands and feet shackled to a ring in the floor. The men took turns questioning him—about the nightclubs he frequented in his wilder years, about his reasons for embracing Islam, about his journey to Pakistan and the heavy boots he bought before leaving—while a hidden camera rolled in the background.

All told, they spent 12 hours with him over two days. By the end they concluded that he had simply found himself “in the wrong place at the wrong time” and “had nothing to do with terrorism and al-Qaida,” according to German intelligence reports.

They discussed their findings with CIA and Pentagon officials, then boarded a plane back to Germany. During a stopover in Washington, D.C., one of the agents visited the local branch of Germany’s foreign intelligence service, the BND, and reported back to headquarters via a secure phone line, saying: “USA considers Murat Kurnaz’s innocence to be proven. He should be released in approximately six to eight weeks.” A few days later, a Pentagon release form for the detainee was printed and awaiting signature.

“At that point, the picture was clear,” says Lothar Jachmann, a retired spy who headed the intelligence-gathering operation on Kurnaz for Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, and was briefed on the Guantanamo visit by one of the agents. “We had nothing on him, and we had gotten feedback that the Americans had nothing on him either. The plan was to let him go.”

But Kurnaz was not set free. Instead, he spent another four years languishing at Guantanamo, where he was repeatedly designated an “enemy combatant,” despite evidence showing he had no known links to terrorist groups.

Lawyers for Guantanamo detainees often argue that their clients are being held based on thin intelligence, but Kurnaz’s case is the first where the record clearly shows that evidence of innocence was ignored to justify his continued detention. His story, pieced together from intelligence reports, newly declassified Pentagon documents, and secret testimony before the German Parliament—much of it never before reported in the United States—offers a rare window into the workings of the secretive system used to hold and try terrorism suspects.

MURAT KURNAZ, the son of Turkish immigrants, was born and raised in Bremen, a rainy north German port city, where he lived with his family in a simple brick row house. His father, Metin, worked the assembly line at a Mercedes Benz plant, while his mother, Rabiye, stayed home with him and his two younger brothers. On Fridays he and his father attended the neighborhood Kuba Mosque, a storefront sanctuary with a barbershop, bookstore, and cavernous teahouse where old men in crocheted skullcaps huddle around plastic tables.

Mosque-goers remember Kurnaz as a shy, quiet boy who didn’t take much interest in religion. “He was a normal Muslim Turk, who prayed once in a while, but was not very observant,” says Nurtekin Tepe, a local bus driver, who has known Kurnaz since he was a child. Instead, Kurnaz spent his time watching Bruce Lee movies, dreaming about motorbikes (he hoped to get one and drive it 110 miles per hour on the autobahn), and lifting weights, often with his neighbor, Selcuk Bilgin, who had many of the same interests, though he was six years older.

This began to change in the fall of 2000. Kurnaz, then 18, was working as a nightclub bouncer; Bilgin had a dead-end job at a supermarket. Some of their friends had started getting in trouble with the law. Feeling there must be something more to life, both men began to take a deeper interest in Islam. Before long, they had cut pork from their diets, grown their beards long, and started attending a new mosque, Abu Bakr, which was located in a dingy, fluorescent-lit office building near Bremen’s main train station and preached a strict brand of Sunni Islam.

Around this time, Kurnaz also started searching for a Muslim bride, and in the summer of 2001 he married Fatima, a young woman who hails from a rural Turkish village. The union was arranged by relatives, and the couple met only once before the ceremony. The idea was to bring her to Germany as soon as her paperwork was sorted out. Meanwhile, Kurnaz and Bilgin made plans to travel to Pakistan. The reason for the trip has been a matter of much debate, but Kurnaz claims he was worried that he didn’t know enough about Islam to be a good Muslim husband and wanted to study the Koran before Fatima’s arrival.

The flight was scheduled to depart Frankfurt on October 3, 2001, less than a month after the 9/11 attacks, but even before Kurnaz and Bilgin boarded the plane their plans began to unravel. Bilgin was stopped at passport control because of an outstanding $1300 fine levied after his dog ran away and attacked a bicyclist. Unable to pay, he called his older brother, Abdullah, in Bremen and asked him to wire the money. Instead, Abdullah phoned the Frankfurt police and urged them not to let Bilgin fly. “My brother is following a friend to Afghanistan to fight the Americans,” he said, according to police reports. “He was stirred up in a Bremen mosque.”

Questioned by police a few days later, Abdullah, who unlike his brother has a poor grasp on German, said his words had been taken out of context; he’d feared Kurnaz and Bilgin might get caught up in the conflict, but didn’t know for a fact that they had plans of fighting. But by that time, the wheels were already in motion. Bilgin was arrested and Bremen police launched a criminal investigation into him, Kurnaz, and two other men who attended Abu Bakr. Germany’s domestic intelligence agency also got in on the act, sending an undercover agent to the mosque to ferret out information.

Meanwhile, Kurnaz, who had gotten on the plane without Bilgin, was traveling through Pakistan, unaware of the commotion his departure had caused.

ON DECEMBER 1, 2001, Kurnaz boarded a bus to the airport in Peshawar, a smoggy city on the country’s northwest border, where he says he planned to catch a plane back to Germany. Along the way, the vehicle was stopped at a routine checkpoint. One of the officers manning it knocked on the window and asked Kurnaz something in Urdu, then ordered him to step off the bus.

Kurnaz expected to show his passport and answer a few questions before being sent on his way. Instead, he was thrown in jail. A few days later, Pakistani police turned him over to U.S. forces, who transported him to Kandahar Air Base, a military installation in the southern reaches of Afghanistan. The Taliban had recently been driven from the region, and the base, built on the rubble of a bombed-out airport, was little more than a cluster of bullet-pocked hangars and decrepit runways. Despite the subzero temperatures, prisoners were kept in large outdoor pens, and a number of them later claimed they were subjected to harsh interrogation tactics. Kurnaz says he was routinely beaten, chained up for days in painful positions, and given electric shocks on the soles of his feet. He also says he was subjected to a crude form of waterboarding, which involved having his head plunged into a water-filled plastic bucket. (The Pentagon, contacted more than a dozen times by email and telephone, would not comment on Kurnaz’s treatment or any other aspect of his case.)

One morning about two months after his arrival in Afghanistan, the detainee was roused before dawn and issued an orange jumpsuit. Then guards shackled and blindfolded him and covered his ears with soundproof earphones before herding him onto a military transport plane.

When the plane touched down more than 20 hours later, Kurnaz was led into a tent where soldiers plucked hairs from his arms, swabbed the inside of his mouth, and gave him a green plastic bracelet with number that would come to define him: 061. Finally, he was led to a crude cell block with concrete floors, a corrugated metal roof, and chain-link walls, which looked out on a sandy desert landscape. Inside his cell, he found a blanket and a thin green mat, a pair of flip-flops, and two translucent buckets, one to be used as a toilet and the other as a sink. He had no idea where he was.

Kurnaz later learned that he landed at Camp X-Ray, a temporary holding pen used to house Guantanamo detainees during the four months when the main prison camp was being built. Even before construction was done, Pentagon officials began to suspect that Kurnaz didn’t belong there. On February 24, 2002, just three weeks after his arrival, a senior military interrogator issued a memo saying, “This source may actually have no al-Qaida or Taliban association.”

IN LATE SEPTEMBER 2002, the three German agents arrived at Guantanamo to interrogate detainee 061. During the trip, they were assigned a CIA liaison, identified only as Steve H., who briefed them on their mission and kept tabs on the interrogations.

Much of the questioning the first day focused on why Kurnaz would choose to travel to Pakistan when war was brewing in the region. The detainee explained that a group of Muslim missionaries had visited his mosque and told him about a school in Lahore where he could study the Koran. But when he arrived there, he found people were suspicious of him because of his light skin and the fact that he spoke no Arabic. Taking him for a foreign journalist, the school turned him away. So he wandered around, staying in mosques and guesthouses, until he was detained near Peshawar (something he also attributed to his light skin and the fact that he spoke German but carried a Turkish passport).

The German agents came away with mixed opinions, according to testimony they later gave before a closed session of German Parliament. (Many other details of their trip were also revealed through that hearing, transcripts of which were obtained by Mother Jones.) The leader of the delegation, who worked for the foreign intelligence service, the BND, saw Kurnaz as a harmless and somewhat naive young man who simply picked a bad time to travel. One of his colleagues, a domestic intelligence specialist, argued it was possible that Kurnaz was on the path to radicalization. But everyone agreed it was highly improbable that he had links to terrorist networks or was involved in any kind of terrorist plot, and none of the agents voiced any objections to letting him go.

Given this fact, Steve H. proposed releasing Kurnaz and using him as a spy, part of a joint operation to infiltrate the Islamist scene in Germany. The German agents apparently took this suggestion to heart, because on day two of their visit, they arrived at the interrogation trailer bearing a chocolate bar and a motorcycle magazine, and asked the detainee point-blank whether he would consider working as an informant. He agreed. (Kurnaz later claimed that he had no intention of actually spying—that, in fact, he would “rather starve to death”—but thought feigning interest might hasten his release.)

That evening, the agents were invited to dinner with the deputy commander of the prison camp. The leader of the delegation later testified that he discussed Kurnaz’s case with him, and according to an investigation by the German newsmagazine Der Spiegel, after the meal, the American official sent a coded message to the Pentagon. A few days later, on September 30, the release form for Kurnaz was printed out. The cover memo, obtained by Mother Jones, notes that Pentagon investigators had found “no definite link/evidence of detainee having an association with al-Qaida or making any specific threat toward the U.S.” and that “the Germans confirmed that this detainee has no connection to an al-Qaida cell in Germany.”

AROUND THE SAME TIME, in October 2002, German police suspended their investigation into Kurnaz and his fellow suspects. No evidence of criminal wrongdoing ever surfaced. “We tapped telephones, we searched apartments, we questioned a large number of witnesses,” Uwe Picard, the Bremen attorney general who led the probe, told me when we spoke in his office, an attic warren stacked waist-deep in files. “We didn’t find anything of substance.”

But police did turn up some troubling bits of hearsay. One of the students at a shipbuilding school Kurnaz attended told investigators that Kurnaz had “Taliban” written on the screen of his cell phone. Then there were the comments of Kurnaz’s mother, who, when questioned by police days after her son’s disappearance, fretted that he had “bought heavy boots and two pairs of binoculars” shortly after the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

Seizing on these details, the German media dubbed Kurnaz the “Bremen Taliban.” This was clearly unsettling to German officials, who just one year after the 9/11 attacks were still reeling from the revelation that three hijackers lived and studied in Germany without ever catching the attention of police or intelligence agencies. Many politicians had serious qualms about letting the German Turk back into the country.

The first sign of these doubts came in the form of a classified report on the Guantanamo visit, which was issued on October 8, 2002, and circulated through the top ranks of the German government. It argues that releasing Kurnaz and using him as a spy would be “problematic,” in that he had “no access to the Mujahideen milieu.” It also notes, “In light of Kurnaz’s possibly imminent release, we should determine whether Germany wants the Turkish citizen back and, given the expected media attention, whether Germany wants to document that everything possible was done to prevent his return.”

Three weeks later, Kurnaz’s case was discussed at the presidential round, a standing Tuesday meeting held at the Germany Chancellery and attended by top officials from the foreign and interior ministries as well as the German security services. The group decided to block his return, and on October 30 the interior ministry issued a secret memo with a plan for keeping him out of the country, which involved revoking his residency permit on the grounds that he had been abroad for more than six months. Germany’s domestic intelligence agency later notified the CIA in writing of the government’s “express wish” that Kurnaz “not return to Germany.”

FOR KURNAZ, the next two years were a blur of interrogations and hours spent locked in his cell. At one point, he claims guards roused him every few hours, part of a coordinated sleep-deprivation campaign dubbed Operation Sandman. He also says he was subjected to pepper-spray attacks, extreme heat and cold, and sexual humiliation at the hands of a scantily clad female guard, who he says rubbed herself against him.

On occasion, he says, punishments were doled out arbitrarily. Each morning a guard would appear at Kurnaz’s cell door and ask him to shove his blanket through the slot. Even when he did so, he claims, he was sometimes accused of not cooperating and given a stint in solitary confinement.

Still, the detainee continued to plead his innocence, telling interrogators at one point that the idea of someone thinking he wanted to fight the Americans “made him feel sick,” according to Pentagon intelligence reports. He also offered repeatedly to take a lie detector test. When asked what he would do if released, he said he would bring his wife to Germany and buy a motorcycle.

Then in June 2004, the Supreme Court ruled that U.S. courts had the authority under federal law to decide whether those held at Guantanamo were rightfully imprisoned. In a bid to keep detainees out of the U.S. justice system, the Bush administration created the Combatant Status Review Tribunals to determine whether detainees had been properly labeled enemy combatants.

Three months later, on September 30, 2004, Kurnaz was led out to one of the interrogation trailers on the fringes of Camp Delta, the main prison complex at Guantanamo. Inside, under the glare of florescent lights, sat three high-ranking military officers at a long table. The “tribunal president,” or judge, was in a high-backed chair in the middle. At his side was Kurnaz’s “personal representative,” who was assigned with helping the detainee argue his case, though he hardly said a word during the proceedings. As for the charges, the only information Kurnaz was given was a summary of the unclassified evidence, which the prosecutor—or “recorder” in Guantanamo parlance—reeled off at the beginning of the hearing. Most of it was circumstantial, like the fact that Kurnaz had flown from Frankfurt to Karachi just three weeks after the 9/11 attacks, and that he allegedly received food and lodging from the Muslim missionary group Tablighi Jamaat. (An apolitical movement with more than 70 million members, it has no known terrorist links, but intelligence agencies worry that its strict brand of Sunni Islam may make it an ideal recruiting ground for jihadists.)

But Kurnaz was hit with one more serious allegation, namely that he was “a close associate with, and planned to travel to Pakistan with” Selcuk Bilgin, who the recorder said “later engaged in a suicide bombing.” Clearly shaken by this charge, Kurnaz interrupted the session, blurting out, “Where are the explosives? What bombs?” according to transcripts of the hearing, which are not verbatim. The tribunal president responded that the details of Bilgin’s fate were classified. Then he asked if the detainee wanted to make a statement. Kurnaz replied, “I am here because Selcuk Bilgin had bombed somebody? I wasn’t aware that he had done that.” Then he gave a meandering speech, mostly a reprise of things he had said during interrogations.

When he was done, the tribunal president asked him if he had anything else to submit, though it’s unclear what more he could have offered; detainees are allowed only limited documentary evidence, and calls for witnesses are generally denied. (Even if prisoners could present more information, it would likely be trumped by the government’s evidence, which, under the tribunal rules laid out by the Bush administration, is presumed to be “genuine and accurate.”) Kurnaz said simply: “I want to know if I have to stay here, or if I can go home…If I go back home, I will prove that I am innocent.”

Later that day, the tribunal determined by a “preponderance of evidence” that Kurnaz had not only been properly designated an enemy combatant, but that he was a member of Al Qaeda. According to the classified summary obtained by Mother Jones, the decision was based almost exclusively on a single memo, written by Brig. General David B. Lacquement shortly before the tribunal convened.

A version of that memo was recently declassified, albeit with large swaths redacted. Among the “suspicious activities” it said Kurnaz engaged in while at Guantanamo: He “covered his ears and prayed loudly during the U.S. national Anthem” and asked how tall a basketball rim was “possibly in an attempt to estimate the heights of the fences.” U.S. District Judge Joyce Hens Green, who reviewed the unredacted version, later wrote that it was “rife with hearsay and lacking in detailed support for its conclusions.”

In contrast to Lacquement’s memo, at least three assessments in Kurnaz’s Pentagon file point to his innocence. Among them is a recently declassified memo, dated May 19, 2003, from Brittain P. Mallow, then commanding general of the Criminal Investigation Task Force, a Pentagon intelligence unit that interrogates and collects information on detainees. It states the “CITF is not aware of evidence that Kurnaz was or is a member of al-Qaida” or that he harbored anyone who “has engaged in, aided or abetted, or conspired to commit acts of terrorism against the U.S.” But the tribunal found these exhibits were “not persuasive in that they seemingly corroborated the detainee’s testimony.” In other words, the Pentagon’s own evidence was ignored because it suggested the detainee was innocent.

What of the allegation that Kurnaz’s would-be traveling companion, Selcuk Bilgin, carried out a suicide attack? As it turns out, Bilgin is alive and residing in Bremen with his wife and two small children. I tracked him down in early January with three phone calls and a visit to his parents’ home, and we met a couple weeks later at his lawyer’s office near the city center. A stocky man with large, dark eyes and a wiry beard, he arrived in a white Audi station wagon with car seats in the rear and was wearing olive cargo pants with a thick black jacket that cinched at the waist. Following his arrest in Frankfurt, he explained, he was held for a few days and then released. “After that, two people from the intelligence services came to talk to me,” he told me. “Some journalists called. Then I just went on with my life.”

Indeed, Bilgin was never charged with any crime, although he was initially suspected of influencing Kurnaz to go to Afghanistan and fight. (Kurnaz’s parents also blamed him for their son’s ordeal, and the two men no longer speak.)

As for the attack Bilgin was accused of carrying out, identified by the Pentagon as the “Elananutus” bombing, it never registered with the media in Germany or the United States (though there is a record of a November 2003 attack on an Istanbul synagogue, allegedly by a man with a similar sounding name—Gokhan Elaltuntas). The Pentagon never bothered to run that allegation by German police; German intelligence agencies were apparently kept out of the loop, too.

“A suicide bomber?” Jachmann, who led the intelligence gathering on Bilgin and Kurnaz, asked incredulously when I explained the allegations. “As far as we knew, he was living right here in Bremen the whole time.”

A WEEK AFTER HIS tribunal, Kurnaz received a visit from a balding thirtysomething man with wire-rimmed glasses who handed him a piece of paper with a handwritten note on it. It read, “My dear son, it’s me, your mother. I hope you’re doing well. This man is Baher Azmy. You can trust him. He’s your lawyer.”

In the three years he had been at Guantanamo, this was the first word Kurnaz had heard from his family. Afraid that the letter would be taken from him, he crumpled it up and stuffed it under his shirt.

Azmy also delivered a second piece of news: He had filed suit against the Bush administration on Kurnaz’s behalf.

Three months later, in January 2005, U.S. District Judge Joyce Hens Green delivered a ruling on Kurnaz’s claim, and those of 62 other prisoners, challenging the legality of the Combatant Status Review Tribunals. Finding that the tribunals were illegal, she used Kurnaz’s case to illustrate the “fundamental unfairness” of the system, particularly its reliance on “classified information not disclosed to the detainees.” (Most of the passages of the ruling dealing with his case were themselves classified until recently, though they were briefly released through a Pentagon slipup and reported by the Washington Post in March 2005.) Green also argued that the tribunal’s choice to ignore evidence of Kurnaz’s innocence was among the strongest signs that the tribunals were stacked against detainees.

But in the end the ruling was just one salvo in an ongoing legal struggle over whether detainees can plead their cases in U.S. courts and had little impact on Kurnaz’s situation. In early November 2005, when the Administrative Review Board (ARB), which conducts annual reviews of detainees’ status, took up his case again, it voted unanimously to uphold his designation as an enemy combatant. According to internal Pentagon emails obtained by Mother Jones, the board failed to weigh evidence submitted by Kurnaz’s lawyers, including a notarized affidavit from Bilgin, which showed that a central charge against the detainee—his alleged association with a suicide bomber—was verifiably false.

Around this time, the tides began to turn on the other side of the Atlantic. German media had gotten wind of their government’s role in Kurnaz’s continued detention, and scandal was brewing. Politicians who had pushed to keep him out of the country were suddenly scrambling to distance themselves from the decision.

Then, in late November, Angela Merkel took over as German chancellor. Though a friend of the Bush administration, she has made no bones about her opposition to the indefinite detentions at Guantanamo. During her first visits to the Oval Office, in January 2006, she pressed President George W. Bush on Kurnaz’s case, the first in a string of negotiations over his fate. In June of that year, the Administrative Review Board reconvened and decided that, after nearly five years of imprisonment, detainee 061 was no longer an enemy combatant.

ON AUGUST 24, 2006, a C-17 cargo plane touched down at Ramstein Air Base, a U.S. military installation 44 miles southwest of Frankfurt. Shackled to the floor in its cargo hold was detainee 061, his face wrapped in a mask and his eyes covered by goggles with blacked-out lenses. Standing watch over him were 15 American soldiers.

On the tarmac, he was handed over to German police, who asked that his handcuffs be removed. Then they escorted him to a nearby Red Cross installation, where his family was waiting.

The reunion was bittersweet: His mother couldn’t stop crying, and his father was so withered and gray that at first Kurnaz mistook him for an older uncle. During the car ride home, a journey of more than 250 miles, Kurnaz learned that his wife, Fatima—the reason he says he traveled to Pakistan—had filed for divorce. All those years with no word from him were more than she could handle. Later in the trip, his father pulled over at a rest stop and his mother poured him some coffee from a thermos in the trunk. Kurnaz was so busy marveling at the stars, which had been drowned out by the floodlights at Guantanamo, that he forgot to drink it.

Kurnaz’s homecoming created a clamor in Germany. By early 2007, the widening scandal was threatening to topple Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier, who as head of the Chancellery under the previous administration was the highest official to formally approve the plan blocking Kurnaz’s return. Around the same time, a special investigative committee of German Parliament began probing Berlin’s role in Kurnaz’s continued detention. The ongoing inquiry has hit some stumbling blocks: CIA transcripts related to the case vanished, and an electronic data system with vital intelligence information was mysteriously erased.

Meanwhile, as the U.S. Supreme Court weighs the legality of the Combatant Status Review Tribunals, Kurnaz’s ordeal is emerging as a key exhibit. Attorney Seth Waxman, who delivered oral arguments on detainees’ behalf last December, wrapped up his comments by recounting the salient details of Kurnaz’s case—a move intended to drive home his claim that the tribunals are an “inadequate substitute” for due process. A decision in the case is expected early this summer.

A reluctant political figure, Kurnaz has done his best to stay out of the fray, turning instead to his old interests. Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, which kept tabs on him after his return, found only one item of note—that he had bought a motorcycle. (He has since shaved off his beard in favor of a biker mustache, started lifting weights again, and bought a cherry-colored Mazda RX-8 with double spoilers, custom alloy wheels, and black-and-red racing seats.) He has also written a memoir, Five Years of My Life: An Innocent Man in Guantanamo, which came out in Germany last year. An English version, with a foreword by rocker Patti Smith, is scheduled to be released in the United States in April, and a movie deal is already in the works. The television newsmagazine 60 Minutes has negotiated an interview exclusive timed to correspond with the book’s release. (Kurnaz declined to be interviewed for this story because of that arrangement.)

A plainspoken account, Five Years of My Life focuses on the daily humiliations and surreal texture of life at Guantanamo, a place where iguanas roam the cell blocks and trials take place in the same rooms as interrogations. In the closing pages, Kurnaz explains why he chose to speak out. “It’s important that our stories are told,” he writes. “We need to counter the endless [official] reports written in Guantanamo itself. We have to speak up and say: I tried to hand back my blanket and got four weeks in solitary confinement.” But Kurnaz doesn’t dwell on his own suffering. Instead he turns the spotlight on the plight of other detainees, including the ones who are still being held. “While I sit here eating chocolate bars and peeling mandarin oranges, they are being beaten and starved,” he writes. “I can eat, drink and sleep much the same as I did five years ago, but I never forget that people are being abused in Cuba.”

Click here for a timeline of Kurnaz’s case.