Photos by Lucian Read.

THE .50 CALIBER Bushmaster bolt action rifle is a serious weapon. The model that Pvt. 1st Class Lee Pray is saving up for has a 2,500-yard range and comes with a Mark IV scope and an easy-load magazine. When the 25-year-old drove me to a mall in Watertown, New York, near the Fort Drum Army base, he brought me to see it in its glass case—he visits it periodically, like a kid coveting something at the toy store. It’ll take plenty of military paychecks to cover the $5,600 price tag, but he considers the Bushmaster essential in his preparations to take on the US government when it declares martial law.

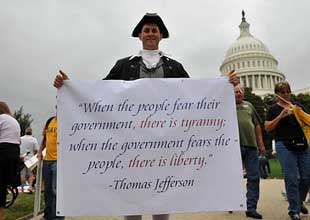

His belief that that day is imminent has led Pray to a group called Oath Keepers, one of the fastest-growing “patriot” organizations on the right. Founded last April by Yale-educated lawyer and ex-Ron Paul aide Stewart Rhodes, the group has established itself as a hub in the sprawling anti-Obama movement that includes Tea Partiers, Birthers, and 912ers. Glenn Beck, Lou Dobbs, and Pat Buchanan have all sung its praises, and in December, a grassroots summit it helped organize drew such prominent guests as representatives Phil Gingrey and Paul Broun, both Georgia Republicans.

There are scores of patriot groups, but what makes Oath Keepers unique is that its core membership consists of men and women in uniform, including soldiers, police, and veterans. At regular ceremonies in every state, members reaffirm their official oaths of service, pledging to protect the Constitution—but then they go a step further, vowing to disobey “unconstitutional” orders from what they view as an increasingly tyrannical government.

Pray (who asked me to use his middle name rather than his first) and five fellow soldiers based at Fort Drum take this directive very seriously. In the belief that the government is already turning on its citizens, they are recruiting military buddies, stashing weapons, running drills, and outlining a plan of action. For years, they say, police and military have trained side by side in local anti-terrorism exercises around the nation. In September 2008, the Army began training the 3rd Infantry’s 1st Brigade Combat Team to provide humanitarian aid following a domestic disaster or terror attack—and to help with crowd control and civil unrest if need be. (The ACLU has expressed concern about this deployment.) And some of Pray’s comrades were guinea pigs for military-grade sonic weapons, only to see them used by Pittsburgh police against protesters last fall.

Most of the men’s gripes revolve around policies that began under President Bush but didn’t scare them so much at the time. “Too many conservatives relied on Bush’s character and didn’t pay attention,” founder Rhodes told me. “Only now, with Obama, do they worry and see what has been done. Maybe you said, I trusted Bush to only go after the terrorists.* But what do you think can happen down the road when they say, ‘I think you are a threat to the nation?'”

In Pray’s estimate, it might not be long (months, perhaps a year) before President Obama finds some pretext—a pandemic, a natural disaster, a terror attack—to impose martial law, ban interstate travel, and begin detaining citizens en masse. One of his fellow Oath Keepers, a former infantryman, advised me to prepare a “bug out” bag with 39 items including gas masks, ammo, and water purification tablets, so that I’d be ready to go “when the shit hits the fan.”

When it does, Pray and his buddies plan to go AWOL and make their way to their “fortified bunker”—the home of one comrade’s parents in rural Idaho—where they’ve stocked survival gear, generators, food, and weapons. If it becomes necessary, they say, they will turn those guns against their fellow soldiers.

PRAY AND I DRIVE through a bleak landscape of fallow winter fields and strip malls in his blue Dodge Stratus as Drowning Pool’s “Bodies”—a heavy metal song once used to torment Abu Ghraib detainees—plays on the stereo. Clad in an oversize black hoodie that hides his military physique, Pray sports an Army-issue buzz cut and is seriously inked (skulls, smoke, an eagle). His father kicked him out of the house at age 14. Two years later, after working jobs from construction to plumbing—”If it’s blue collar, I’ve done it”—he tried to enlist. It wasn’t long after 9/11, and he was hell-bent on revenge. The Army turned him down. Blaming the “THOR” tattooed across his fist, Pray tried to burn it off. On September 11, 2006, he approached the Army again and was accepted.

Now Pray is both a Birther and a Truther. He believes he is following an illegitimate, foreign-born president in a war on terror launched by a government plot—9/11. He admires soldiers like Army reservist Major Stefan Frederick Cook, who volunteered for a deployment last May and then sued to avoid it—claiming that Obama is not a natural-born citizen and is thus unfit for command. Pray himself had been eager to go to Iraq when his own unit deployed last June, but he smashed both knees falling from a crane rig and the injuries kept him stateside. In September, he was demoted from specialist to private first class—he’d been written up for bullshit infractions, he claims, after seeking help for a drinking problem. His job on base involves operating and maintaining heavy machinery; the day before we met, he and his fellow “undeployables” had attached a snowplow to a Humvee, their biggest assignment in a while. He spends idle hours at the now-quiet base researching the New World Order and conspiracies about swine flu quarantine camps—and doing his best to “wake up” other soldiers.

Pray isn’t sure how to do this and still cover his ass. He talks to me on the record and agrees to be photographed, even as he hints that the CIA may be listening in on his phone. Although I met him through contacts from the group’s Facebook page, Pray, fearing retribution, keeps his Oath Keepers ties unofficial. (Rhodes encourages active-duty soldiers to remain anonymous, noting that a group with large numbers of anonymous members can instill in its adversaries the fear of the unknown—a “great force multiplier.”) For a time, Pray insisted we communicate via Facebook (safer than regular email, he claims). Driving me from the mall back to my motel, he takes a new route. He says unmarked black cars sometimes trail him. It sounds paranoid. Then again, when you’re an active-duty soldier contemplating treason, some level of paranoia is probably sensible.

The next afternoon we join Brandon, one of Pray’s Army buddies, for steaks. Sitting in a pleather booth at Texas Roadhouse, the young men talk boastfully about their military capabilities and weapons caches. Role-playing the enemy in military exercises, Brandon says, has prepared him to evade and fight back against US troops. “I know their tactics,” brags Pray. “I know how they do room sweeps, work their convoys—if we attack this vehicle, what the others will do.”

A strapping Idahoan, Brandon (who doesn’t want his full name used) enlisted as a teenager when he got his girlfriend pregnant and needed a stable job, stat. (She lost the baby and they split, but he’s still glad he signed up.) Unlike his friend, he doesn’t think the United Nations must be dismantled, although he does agree that it represents the New World Order, and he suspects that concentration camps are being readied in the off-limits section of Fort Drum. He sends 500 rounds of ammunition home to Idaho each month.

Pfc. Lee Pray vows he’ll fight to the death if a rogue US government “forces us to engage.”EVERY YEAR ON April 19, history buffs gather on the village green in Lexington, Massachusetts, to reenact the first battle of the Revolutionary War. For Stewart Rhodes, it was the ideal setting to unveil the organization his followers consider the embodiment of a second American Revolution.

Pfc. Lee Pray vows he’ll fight to the death if a rogue US government “forces us to engage.”EVERY YEAR ON April 19, history buffs gather on the village green in Lexington, Massachusetts, to reenact the first battle of the Revolutionary War. For Stewart Rhodes, it was the ideal setting to unveil the organization his followers consider the embodiment of a second American Revolution.

Rhodes, 44, is a constitutional lawyer—his 2004 Yale Law School paper, “Solving the Puzzle of Enemy Combatant Status,” won the school’s award for best paper on the Bill of Rights. He’s now working on a book tentatively titled We the Enemy: How Applying the Laws of War to the American People in the War on Terror Threatens to Destroy Our Constitutional Republic. Raised in the Southwest, Rhodes enlisted in the Army after high school, receiving an honorable discharge after he injured his spine during a night parachute jump. He enrolled at the University of Nevada and in 1998, after graduating, landed a job supervising interns for Congressman Ron Paul. Rhodes has also worked as a firearms instructor and a sculptor—for Vegas’ MGM Grand hotel, he produced a fiberglass Minuteman statue—and has practiced law in small-town Montana (“Ivy League quality without Ivy League expense”). He writes a gun-rights column for SWAT magazine. He’s a libertarian, staunch constitutionalist, and devout Christian.

It was while volunteering for Ron Paul’s doomed presidential bid that Rhodes decided to abandon electoral politics in favor of grassroots organizing. As an undergrad, he had been fascinated by the notion that if German soldiers and police had refused to follow orders, Hitler could have been stopped. Then, in early 2008, SWAT received a letter from a retired colonel declaring that “the Constitution and our Bill of Rights are gravely endangered” and that service members, veterans, and police “is where they will be saved, if they are to be saved at all!”

Rhodes responded with a breathless column starring a despotic president, “Hitlery” Clinton, in her “Chairman Mao signature pantsuit.” Would readers, he asked, obey orders from this “dominatrix-in-chief” to hold militia members as enemy combatants, disarm citizens, and shoot all resisters? If “a police state comes to America, it will ultimately be by your hands,” he warned. You had better “resolve to not let it happen on your watch.” He set up an Oath Keepers blog, asking soldiers and veterans to post testimonials. Word spread. Military officers offered assistance. A Marine Corps veteran invited Rhodes to speak at a local Tea Party event. Paul campaigners provided strategic advice. And by the time Rhodes arrived in Lexington to speak at a rally staged by a pro-militia group, a movement was afoot.

Rhodes stood on the common that day before a crowd of about 400 die-hard patriot types. He spoke their language. “You need to be alert and aware to the reality of how close we are to having our constitutional republic destroyed,” he said. “Every dictatorship in the history of mankind, whether it is fascist, communist, or whatever, has always set aside normal procedures of due process under times of emergency…We can’t let that happen here. We need to wake up!”

He laid out 10 orders an Oath Keeper should not obey, including conducting warrantless searches, holding American citizens as enemy combatants or subjecting them to military tribunals (a true Oath Keeper would have refused to hold José Padilla in a military brig), imposing martial law, blockading US cities, forcing citizens into detention camps (“tyrannical governments eventually and invariably put people in camps”), and cooperating with foreign troops should the government ask them to intervene on US soil. In Rhodes’ view, each individual Oath Keeper must determine where to draw the line.

The crowd was full of familiar faces from patriot rallies and town hall meetings, with an impressive showing by luminaries of the rising patriot movement. There was Richard Mack, a former Arizona sheriff who had refused to enforce the Brady Law in the mid-’90s. Also present was Mike Vanderboegh, whose Three Percenter movement styles itself after the legendary 3 percent of American colonists who took up arms against the British. Rhodes singled out Marine Charles Dyer, a.k.a. July4Patriot—whose YouTube videos advocate armed resistance—as a “man of like minds.” When Rhodes finished, Captain Larry Bailey, a retired Navy SEAL, Swift Boater, and founder of the anti-antiwar group Gathering of Eagles, asked the crowd to raise their right hands and retake their oath—not to the president, but to the Constitution.

*Correction: An earlier version of this story omitted “Maybe you said.” We have corrected the error.

RHODES’ TIMING WAS impeccable. Twelve days earlier, the Department of Homeland Security had issued a report warning that a black president, weak economy, and high unemployment rate had created a “fertile recruiting environment” for right-wing extremists—”disgruntled” vets from Iraq and Afghanistan, the report noted, could bring combat know-how to domestic terrorist groups. Predictably, veterans groups went ballistic, and the report itself became a potent Oath Keepers recruiting tool. “The No. 1 focus of DHS is not Islamic terrorists—it is me and you,” Rhodes told followers. “They will unleash the government against you, silence you and suppress you!”

Lee Pray and his pal Brandon were left behind with injuries when their unit shipped off to Iraq. They spend their idle hours preparing for the day the government goes too far.Oath Keepers collaborates regularly with like-minded citizens groups; last Fourth of July, Rhodes dispatched speakers to administer the oath at more than 30 Tea Party rallies across America. At last fall’s 9/12 march on Washington, he led a contingent of Oath Keepers from the Capitol steps down to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Afterward, Oath Keepers cohosted a banquet with the hawkish Gathering of Eagles. This February, a member of the group organized a Florida Freedom Rally featuring Joe the Plumber and conservative singer Lloyd Marcus. (Sample lyrics: Mr. President! Your stimulus is sure to bust / it’s just a socialistic scheme / The only thing it will do / is kill the American Dream.)

Lee Pray and his pal Brandon were left behind with injuries when their unit shipped off to Iraq. They spend their idle hours preparing for the day the government goes too far.Oath Keepers collaborates regularly with like-minded citizens groups; last Fourth of July, Rhodes dispatched speakers to administer the oath at more than 30 Tea Party rallies across America. At last fall’s 9/12 march on Washington, he led a contingent of Oath Keepers from the Capitol steps down to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Afterward, Oath Keepers cohosted a banquet with the hawkish Gathering of Eagles. This February, a member of the group organized a Florida Freedom Rally featuring Joe the Plumber and conservative singer Lloyd Marcus. (Sample lyrics: Mr. President! Your stimulus is sure to bust / it’s just a socialistic scheme / The only thing it will do / is kill the American Dream.)

Rhodes has become a darling of right-wing pundits. In a column last October, Pat Buchanan predicted that “Brother Rhodes is headed for cable stardom.” Glenn Beck has cited the group as a “phenomenal” example of the “patriot revival movement,” while Lou Dobbs declared that its platform “should give solace and comfort to the left in this country.” Conspiracy-radio king Alex Jones even put an Oath Keepers segment, including footage of the Lexington speech, on his hit DVD Fall of the Republic. “I can’t stress enough how much your organization is scaring the globalists,” he told Rhodes on his show.

All this attention has put Oath Keepers on the radar of anti-hate groups. Last year, the Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center both name-checked the group in their reports on rising anti-government extremism. “They think the word ‘patriot’ is a smear,” Rhodes countered during his Dobbs segment. SPLC’s Mark Potok “wants to lump us in with white supremacists and neo-Nazis, and of course make the insinuation that we’re the next McVeigh.” But such attacks have only raised Oath Keepers’ profile. After a combative Hardball interview in October—host Chris Matthews asked Rhodes whether Oath Keepers had the “firepower to stand up against the federal government”—the group says it gained 2,000 members in three days.

As of mid-January, according to Rhodes, Oath Keepers had at least one chapter in every state and was adding dozens of members daily. Some 14,000 people had signed up as members on the Oath Keepers website while more than 15,000, including dozens of military recruiters, had done so on Facebook. And that doesn’t include those who, fearing reprisal, do their networking offline. Volunteers are in the process of sending out some 1,000 “constitutional care packages” complete with Oath Keepers patches to soldiers serving overseas.

IT IS EASY ENOUGH to dismiss the Oath Keepers as (in the words of Britain’s Independent) “right-wing crackpots” or “extremist nimrods” (Huffington Post). CNN stressed the group’s conspiracy theories in its series on militias. But beyond the predictable stereotypes, “the reality is a lot of them are fairly intelligent, well-educated people who have complex worldviews that are thoroughly thought out,” says author David Neiwert, who has been following the patriot movement closely since the ’90s.

Rhodes’ vision is simple—”It’s the Constitution, stupid.” He views the founding blueprint the way fundamentalist Christians view the Bible. In Rhodes’ America, sovereign states—”like little labs of freedom”—would have their own militias and zero gun restrictions. He would limit federal power to what’s stated explicitly in the Constitution and Bill of Rights; any new federal law affecting the states would require a constitutional amendment. “If your state goes retarded,” he says, “you can move to another state and vote with your feet.” The president would be stripped of emergency powers that allow him to seize property, restrict travel, institute martial law, and otherwise (as the Congressional Research Service has put it) “control the lives of United States citizens.” The Constitution, Rhodes explains, “was created to check us in times of emergency when we are freaking out.”

Much of this is familiar rhetoric, part of a continuous strain in American politics that reemerged most recently during the 1990s. Back then, a similar combination of recession and Democratic rule led to the rise of citizen militias, the Posse Comitatus movement, and Oath Keepers-type groups like Police & Military Against the New World Order. But those groups had little reach. Nowadays, through the power of YouTube and social networking, and with a boost from the cable punditry, Oath Keepers can reach millions and make its message part of the national conversation—furthering the notion that citizens can simply disregard a government they loathe. “The underlying sentiment is an attack on government dating back to the New Deal and before,” says author Neiwert. “Ron Paul has been a significant conduit in recent years, but nothing like Glenn Beck and Michele Bachmann and Sarah Palin—all of whom share that innate animus.”

Oath Keepers’ strength derives from what Rhodes calls “a very powerful common bond” (the vow of service) as well as the uniform—”a powerful source of credibility and respect” that allows members to “throw their weight into any movement…and tip any election.” Rhodes is wary of “old-party asshole RINOs” (Republicans in name only)—he mentions Dick Armey, the former House majority leader turned Tea Party sponsor—who in his view are merely out to hijack the grassroots.

Most Oath Keepers may intend to disobey their commanders only in the instances the group highlights. But the group’s ideas also appeal to extremists like Daniel Knight Hayden, whose inflammatory tweets last April (“START THE KILLING NOW!”) signaled his intent to wreak havoc at a Tax Day protest. On the morning of April 15 he sent out a tweet touting Oath Keepers, followed by “Locked AND loaded for the Oklahoma State Capitol. Let’s see what happens.” (The FBI arrested him at home a few hours later; he was eventually convicted for transmitting interstate threats.) Rhodes vigorously denounced Hayden, but the episode hinted at the power of the group’s language. Rhetoric like Rhodes’ (“Do you want them to kick down your door in body armor?”) can have “an unhinging effect” on people inclined toward violent action, Neiwert explains. “It puts them in a state of mind of fearfulness and paranoia, creating so much anger and hatred that eventually that stuff boils over.”

In the months I’ve spent getting to know the Oath Keepers, I’ve toggled between viewing them either as potentially dangerous conspiracy theorists or as crafty intellectuals with the savvy to rally politicians to their side. The answer, I came to realize, is that they cover the whole spectrum.

ON A CLEAR September evening, I found myself in suite 610 at the Texas Station casino in North Las Vegas mingling with two dozen Oath Keepers state leaders, directors, and hardcore devotees. It was past midnight, but the place—down to the American flag wallpaper in the bathroom—was awake with the sense of a movement primed to burst into the national consciousness. Mississippi director Chris Evans, who sports a long beard and cowboy hat, declared in his pronounced drawl that this gathering was so important to him that for the first time since 9/11 he’d succumbed to the “invasive breach of privacy” required to fly here. Rand Cardwell, who organized multiple chapters in Tennessee, only woke up, he told me, when the government began bailing out big companies and left ordinary people in the cold: “Pain causes action,” he said. For others here, the aha moment came with the Patriot Act or when federal troops and contractors confiscated weapons in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

As techies swarmed around laptops discussing website tweaks, two shy Midwesterners who hoped to become state directors told me they were eager to learn recruiting tips. An energetic young veteran griped that hate-crime bills aim to police people’s thoughts, and that the “Don’t Tread on Me” bumper stickers popular with constitutionalists raise enough suspicion these days to get a person pulled over by the authorities. Over bottled water and microbrews, they swapped tips on how to involve members in state militias, spread viral YouTube videos of soldiers reaffirming their oaths, and reach out to other patriots. They boasted of recruiting at gun shows, approaching politicians and cops, and stuffing leaflets into magazines in veterans hospital waiting rooms.

The three-day conference was called posthaste after Rhodes realized that his group was growing beyond his control. On the first night, over a casino buffet of barbecue, goopy Chinese food, and key lime pie, core members scrutinized printouts of potential organizational structures before heading upstairs to sign legal documents, pick a board of directors, and start nominating state representatives.

Rhodes caught wind of my presence during the introductory meet and greet. Taking me aside, he told me he’d decided reporters weren’t welcome. After I protested that the Oath Keepers website had described the conference as open to the public, he offered to refund my $300 entrance fee. Then I told him I’d read his Yale paper and shared many of his concerns about executive power; I really wanted to hear what Oath Keepers had to say. In the end, he agreed to let me stay and eventually invited me to hang out with the inner circle.

The next morning, in a casino ballroom, a hundred or so Oath Keepers exchanged business cards and schmoozed in between speeches about constitutional law, American Revolutionary history, and a soldier’s obligation to disobey illegal orders—Nuremberg references on full display. Clad in suits, or slacks with button-downs, most of them could have been attending an insurance convention. One Oath Keeper handed out Gadsden-flag bumper stickers, while others sold T-shirts, baseball caps, and polo shirts featuring the group’s minuteman logo and motto: “Not on our watch.” There was a raffle, and James Sugra, one of the masterminds behind Ron Paul’s fundraising “money bombs,” scored a huge framed replica of the Constitution. To enthusiastic applause, a driver in the Lucas Oil Late Model Dirt Series (a hot new cross between NASCAR and monster truck rallies) announced that the Oath Keepers would get free ad space on his car. Their logo would be seen on television sets across America. During the talks, I sat between a libertarian who had biked across America, stopping at police stations to hand out recruiting materials, and a first-generation Chinese American stay-at-home dad from San Francisco who invited me to my local chapter’s winter survivalist training and rifle practice—extracurriculars, he assured me.

Oath Keepers is officially nonpartisan, in part to make it easier for active-duty soldiers to participate, but its rightward bent is undeniable, and liberals are viewed with suspicion. At lunch, when I questioned my tablemates about the Obama-Hitler comparisons I’d heard at the conference, I got a step-by-step tutorial on how the president’s socialized medicine agenda would beget a Nazi-style regime.

I learned that bringing guns to Tea Party protests was a reminder of our constitutional rights, was introduced to the notion that the founding fathers modeled their governing documents on the Bible, and debated whether being Muslim meant an inability to believe in and abide by—and thus be protected by—the Constitution. I was schooled on the treachery of the Federal Reserve and why America needs a gold standard, and at dinner one night, Nighta Davis, national organizer for the National 912 Project, explained how abortion-rights advocates are part of a eugenics program targeting Christians. I also met Lt. Commander Guy Cunningham, a retired Navy officer and Oath Keeper who in 1994 took it upon himself to survey personnel at the 29 Palms Marine Corps base about their willingness to accept domestic missions and serve with foreign troops. A quarter of the Marines he polled said that they would be willing to fire on Americans who refused to disarm in the face of a federal order—a finding routinely cited by militia and patriot groups worried about excessive government powers.

From the podium, ex-sheriff Mack told the crowd that he wished he’d been the officer ordered to escort Rosa Parks off the bus, because not only would he have refused, he would have helped her home and stood guard there. These days, he said, it’s not African Americans who are under attack, but Christians, constitutionalists, and people who uphold family values: This time “it’s going to be Rosa Parks the gun owner, Rosa Parks the tax evader, or Rosa Parks the home-schooler.”

Mack runs the “No Sheriff Left Behind” campaign encouraging state and local authorities to disregard federal laws that they believe violate states’ rights. During the 1990s, he successfully eviscerated a Brady Law provision requiring sheriffs to run background checks on handgun purchasers. Another sheriff who spoke, Mark Gower of Iron County, Utah, uses Mack’s precedent to refuse to act against property owners who violate the Endangered Species Act. The conference’s lifetime achievement award went to Army Specialist Michael New, discharged in 1996 for refusing to wear a United Nations helmet and patch while serving in Germany.

Oath Keepers steers clear of certain issues. Personally, Rhodes would prefer the list of objectionable orders to include detaining foreigners indefinitely at facilities like Guantanamo. And while he argues that torture should never be legal, the group takes no official stance on America’s war on terror or overseas engagements. After an Oath Keeper who is also a member of Iraq Veterans Against the War touted IVAW repeatedly on Oath Keepers’ Web forum, Rhodes deleted the guy’s online testimonial. “The IVAW have their own totalitarian mindset,” he told me. “I don’t like communists any more than I like Nazis.”

On the conference’s final day, National 912 Project chairman Patrick Jenkins stepped up to talk about the National Liberty Unity Summits his group was organizing in cooperation with Oath Keepers. They would provide a chance, he said, for patriots to forge a common agenda and a plan to carry it out. At the first summit, in December, attendees included representatives of groups from FairTax Nation to the Constitution Party to Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum. On hand were Ralph Reed Jr. (former director of Pat Robertson’s Christian Coalition and recent founder of the Faith and Freedom Coalition), Larry Pratt (head of Gun Owners of America), and Tim Cox (founder of Get Out of Our House, an organization praised on Fox News for its goal of replacing business-as-usual incumbents with “ordinary folks”). Most notable were representatives Broun and Gingrey, who according to summit organizer Nighta Davis have expressed willingness to introduce legislation crafted by summit attendees. (So, Davis says, have Steve King [R-Iowa] and Michele Bachmann [R-Minn.]. None of the representatives agreed to comment for this story.)

The December gathering was merely a windup. In mid-April, another summit is planned to coincide with a huge gun-rights march and a Tax Day Tea Party rally in Washington organized by Dick Armey’s FreedomWorks PAC and the American Liberty Alliance—whose home page touts Oath Keepers as a key part of “the Movement.” Organizers expect hundreds of thousands to turn out. The Oath Keepers will be there en masse.

IN VEGAS, Rhodes took me aside repeatedly to explain that many of those in attendance—including featured speakers like “Patriot Pastor” Garrett Lear (“When a government doesn’t obey God, we must reform it”)—might not represent Oath Keepers’ official message. He and his Web staff have been overwhelmed, he told me, by the amount of policing required to keep people from posting “off message” commentary encouraging violence or racism. Last December, they shut down one forum because too many posters were using it to recruit for militias. The Constitution, of course, allows citizens to form militias so long as their intent is to defend and not overthrow the government, but active-duty soldiers can lose security clearances or get demoted for associating with them. Rhodes advises members to go ahead and join—just not in Oath Keepers’ name. “As a matter of strategy, it is best to keep the two separate,” he wrote in a post.

There may also be serious downsides for a soldier who follows through on his Oath Keepers pledge. Disobeying orders can mean discharge or imprisonment. “You have every right to disobey an order if you think it is illegal,” says Army spokesman Nathan Banks. “But you will face court-martial, and so help you God if you are wrong. Saying something isn’t constitutional isn’t going to fly.”

A soldier like Charles Dyer, who in his July4Patriot persona advocated armed resistance against the government, could risk charges of treason. As a Marine sergeant based out of Camp Pendleton, Dyer posted videos to YouTube last year, his face half-covered with a skull bandana. “With the DHS blatantly calling patriots, veterans, and constitutionalists a threat, all that I have to say is, you’re damn right we’re a threat,” he said in one. “We’re a threat to anyone that endangers our rights and the Constitution of this republic…We’re gathering in defense of our way of life.” For a while, he ran a training compound in San Diego, teaching civilians his Marine combat skills.

Dyer, who with Rhodes’ blessing represented Oath Keepers at an Oklahoma Tea Party rally on July 4, was charged under the Uniform Code of Military Justice with uttering “disloyal” statements. He ultimately beat the charge, left the Marines, and reappeared unmasked on YouTube encouraging viewers to join him at his makeshift training area in Duncan, Oklahoma—”I’m sure the DHS will call it a terrorist training camp.” In January, Dyer was arrested on charges of raping a seven-year-old girl. When sheriff’s deputies raided his home, they found a Colt M-203 grenade launcher believed to have been stolen from a California military base. He now faces federal weapons charges and is being hailed by fringe militia groups like the American Resistance Movement as “the first POW of the second American Revolution.”

Shortly after I asked Rhodes about Dyer—before his arrest hit the news—his testimonial vanished from the group’s website. Rhodes once endorsed Dyer in glowing terms, but now claims he was never a member because he hasn’t paid dues. Yet Dyer publicly referred to himself as an Oath Keeper, and Rhodes had previously insisted—to Lou Dobbs and anyone else who would listen—that you didn’t need to pay dues to be a member.

In an interview prior to Dyer’s arrest, Andrew Sexton, another uniformed YouTube star who argues the need for armed resistance, criticized Dyer for making himself a target. Sexton, an Army reservist who served in Afghanistan with US Special Operations Command, also keeps his Oath Keepers ties under the radar. Most soldiers, he told me, don’t talk openly about such things, but it’s easy enough to tell which ones have been woken up. The Department of Defense, Sexton added, will be shocked by the number of service members willing to turn against their commanders when the time comes. “It’s an absolute reality,” he says. He views last April’s DHS report on right-wing extremists as a “preemptive attack because they know it’s coming.”

Rhodes isn’t calling for violence—indeed, he insists that his group is about laying down arms rather than turning them on citizens. Yet when he writes that “the oath is like kryptonite to tyrants, as the Founders intended. The time has come for us to use it to its full effect,” some followers take that as a call for drastic action.

Chip Berlet, of the watchdog group Political Research Associates, who has studied right-wing populist movements for 25 years, equates Rhodes’ rhetoric to yelling fire in a crowded theater. “Promoting these conspiracy theories is very dangerous right now because there are people who will assume that a hero will stop at nothing.” What will happen, he adds, “is not just disobeying orders but harming and killing.”

Rhodes acknowledges that there are certain risks. Freedom “is not neat or tidy,” he says. “It’s messy.” For example, he concedes that “there may be a downside” to police refusing to engage during a riot situation. “Someone could be beaten or raped, but the potential risks involved are far less dangerous than having soldiers or police always do whatever they are told.”

LEE PRAY thinks Rhodes downplays the threat Oath Keepers represents to a rogue administration. “They have to be careful because otherwise they will be labeled as terrorists,” he says. “You have to read between the lines, but I wish they were more up-front with their members.”

It’s not hard to see the appeal of Oath Keepers for guys like Pray and Brandon, frustrated young men nervous about their future prospects. They signed up to defend the greatest country in the world, only to be cast aside. Even their injuries were suffered ingloriously. Brandon can’t sit for long after being flung from a pickup truck; Pray now walks with a cane, possibly for good. The men sincerely believe their country is headed for disaster, but as broken warriors they are powerless to do anything about it. They have tried writing to Congress, signing petitions, and voting, all to no avail. Oath Keepers offers a new sense of pride and comradeship—of being part of something momentous.

And when the time comes, Pray insists he is battle ready. “If the government continues to ignore us, and forces us to engage,” Pray says, “I’m willing to fight to the death.” Brandon, for his part, is resigned about their odds fighting the US military. “If we take up arms, realistically we would lose, and they would label us as terrorists,” he says. Pray nods sadly in agreement. But they’ll take their chances. They consider it their duty.