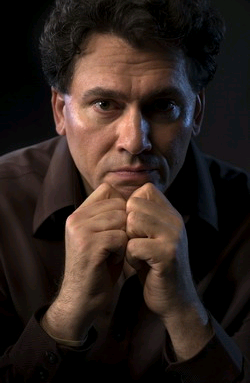

Illustration: Steve Wacksman

As Michigan state legislators considered a plan to curb illegal immigration last fall, they heard dramatic testimony from a man named Kamal Saleem. He warned the lawmakers that Islamic extremists were sneaking into the country with nefarious plans. “If we don’t pass this bill,” the fiftysomething Lebanese American told them, “we will be legalizing terrorism to be part of our culture.”

Saleem’s testimony was rooted in an extraordinary backstory: He purports to have spent half a decade recruiting Islamists in America—before finding Christ and laying down arms. “I came to the United States of America not to love you all,” he declared at a rally on the Capitol steps after the hearing. “I came to…destroy this country as a terrorist.”

Over the last five years, Saleem’s tale of terror and redemption has made him a minor celebrity among Christian conservatives. Part national-security wonk, part evangelist, he is one of a handful of self-described “ex-terrorists” who have emerged in the post-9/11 era to share their experiences. He has spoken in state capitols, at the Air Force Academy, and at colleges and churches around the country. He has been a guest on Pat Robertson’s 700 Club and started his own nonprofit, Koome Ministries, of which he was the only full-time employee in 2009. Tax records show Saleem earned $48,000 from the ministry that year—and had a $39,000 expense account—while Koome took in nearly $100,000 in donations and grants.

According to his memoir, The Blood of Lambs, Saleem, who grew up in Lebanon, broke into the terror biz at the age of seven by running weapons—strapped onto sheep—for Palestine Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat (who kissed his forehead at a public ceremony, “his breath bearing tales of garlic and onion”). As a teenager, he helped run a terrorist camp in the Libyan desert at the behest of Moammar Qaddafi. He visited Iraq, where he rubbed shoulders with Saddam Hussein. In the late 1970s, he traveled to Afghanistan, working alongside the mujahideen and CIA spooks to beat back the Soviets. A Kansas City Star columnist skeptically dubbed him the “Forrest Gump of the Middle East.“

“I came to…destroy this country as a terrorist.” —Kamal Saleem kamalsaleem.comSaleem claims that the Muslim Brotherhood has put a $25 million bounty on his head, and that there have been attempts to earn it: After a 2007 event in Chino Hills, California, he writes in his book, he returned to his Holiday Inn to find his room ransacked and a band of dangerous Middle Easterners on his trail. Saleem describes calling the police to alert them to an assassination attempt. Local law enforcement, however, has no record of any such incident.

“I came to…destroy this country as a terrorist.” —Kamal Saleem kamalsaleem.comSaleem claims that the Muslim Brotherhood has put a $25 million bounty on his head, and that there have been attempts to earn it: After a 2007 event in Chino Hills, California, he writes in his book, he returned to his Holiday Inn to find his room ransacked and a band of dangerous Middle Easterners on his trail. Saleem describes calling the police to alert them to an assassination attempt. Local law enforcement, however, has no record of any such incident.

That’s just one of many of Saleem’s tales that don’t stand up to scrutiny. (Through a spokeswoman, Saleem refused to comment for this story.) Doug Howard, a professor of Middle Eastern history at Michigan’s Calvin College, first encountered Saleem in 2007, when he was invited to speak at the school. Howard quickly became suspicious: For starters, Saleem claimed to be a descendant of the “Grand Wazir of Islam,” a position that doesn’t exist. Howard dug deeper and discovered that Saleem’s original name was Khodor Shami—and that for more than a decade before outing himself as a former terrorist he had worked for Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network and James Dobson’s Focus on the Family. (CBN declined to comment. Focus on the Family confirmed Saleem was an employee but would not comment further.)

A former friend also sheds light on Saleem’s past. Wally Winter, a nurse in Albuquerque, New Mexico, first met him when they both worked at a hospital in Abu Dhabi in 1979. Two years later, he got a phone call from Saleem; he’d come to the United States and needed help. Winter says he welcomed Saleem into his spare bedroom, opened a bank account for him, taught him how to drive, and helped get him a job at the hospital where he worked near Oklahoma City. When Winter moved to the city, Saleem came along. “He had no money,” Winter says. “I had to drive him wherever he was going.” The two were close; Winter would bring Saleem to his parents’ home on holidays.

Winter recalls his former roommate as a devout Muslim whose yarns often lapsed into wild exaggeration. “He could sell swampland in Louisiana,” Winter says. “I really do not believe the story about the terrorism. I totally believe that he would make up something like that to either make money or become well known.”

A cloud of doubt also hangs over Saleem’s frequent speaking partner, Walid Shoebat, another converted ex-terrorist who runs a ministry and whose books include Why I Left Jihad and Why We Want to Kill You. Shoebat has offered contradicting statements on whether he uses an assumed name. An Israeli bank he claims to have bombed in the 1970s has said it has no record of the incident; a spokesman for Shoebat says that’s probably because the attack “caused no injury and minor damage.”

Wouldn’t authorities have some interest in someone who claims to have been involved in some of the biggest Middle Eastern militant movements of the 1970s and ’80s? Saleem claims that local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies, including the FBI, have “reached out” to him to learn about “the Islamist mindset and tactics.” But Kathleen Wright, an FBI spokeswoman, says she has “no information that Kamal Saleem has spoken at an FBI-sponsored event.” She could not say definitively whether the bureau had ever been in contact with him. Winter, for his part, says he has never been questioned by authorities about his former roommate.

Ironically, this apparent lack of official scrutiny may be the strongest evidence against Saleem’s credibility. As Dawud Walid, executive director of the Michigan branch of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, puts it, “The FBI or the Department of Homeland Security don’t let people who are terrorists into the country and not detain them just because they claim they got the Holy Ghost.”

This story originally ran in the March/April 2012 issue with the headline “Sleeper Sell.”