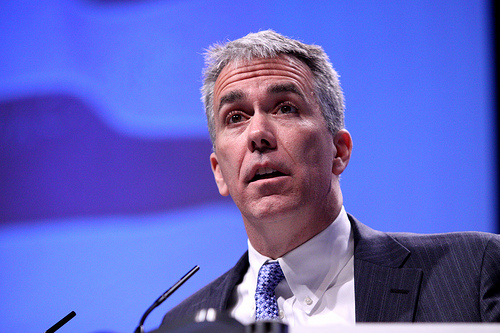

At a summerfest with constituents.Danny Wilcox Frazier

WHEN I FIRST MEET TAMMY DUCKWORTH in her suburban Chicago campaign office, she nearly mows me over with her $4,000 titanium wheelchair as she cruises a narrow hallway festooned with military mementos. “I’m actually looking for scissors,” she says cheerfully. “They don’t let the candidate have scissors! They’re afraid I’m gonna roll over and hurt myself.”

Mission accomplished, she cuts a pair of shiny silver military insignia out of their packaging to send to a World War II vet she talked to that morning. As she fidgets with the box in her lap, her floral print dress shifts to reveal two carbon-fiber calves, one with a camo design, the other red, white, and blue. They connect to metal extensions that end in polymer-coated feet clad in black saddle shoes. A cane rests between her legs.

Whether or not Duckworth wins a seat in Congress, she’ll be celebrating this November. That’s because November 12 is her “alive day“—the day she and her three Black Hawk crewmates get together and remember the insurgent attack in 2004 in the skies near Baghdad that brought down their chopper and nearly killed them all. Duckworth left both legs behind.

It’s a loss that gave her “a great gift of perspective,” she tells me. “At the end of the day it’s not about Democrats or Republicans. It’s not about Obama or Romney. It’s about the fact that on that day, those men carried me out when they didn’t have to. They thought I was dead.”

Her copilot that day, Chief Warrant Officer Daniel Milberg (who’s preparing to deploy on his third overseas tour since 9/11), says if anyone is a hero it’s Duckworth. “Too many people, military people included, are too willing to have a pity party,” he told me. “Man, there’s no time for pity parties—look at this gal.”

Thirteen months after the attack, Duckworth was back on Army duty on titanium legs, and was training to fly again. By then she had also jumped into public service, advocating better treatment for vets and winning friends with her sunny disposition. (She’s been known to work out in T-shirts reading “Dude, where’s my leg?” and “Lucky for me he’s an ass man.”) Even after she became a vocal opponent of the Iraq War, lost a bid for Congress in 2006, and went to work for the Obama administration, her story drew praise from conservatives and liberals alike. “Miracle on the Hudson” pilot Chesley Sullenberger III has called it “beyond inspiring.”

Now, Duckworth is running for Congress against Republican incumbent Joe Walsh, a tea party freshman noted for calling President Obama a “tyrant” and engaging in legal battle over his child support payments. Should Duckworth win, she would be the first-ever woman injured in combat to be elected to national office. But to Democrats, the 44-year-old trilingual daughter of a Marine and a Thai immigrant represents much more: the changing face of America, a potential leader for the rights of women and immigrants, and a champion of assistance to the poor, jobless, and disabled. “She could play a key role nationally like no one else,” says Rep. Mike Quigley (D-Ill.), one of her political mentors. “There are few districts in the country where the choice between candidates so closely reflects the divide in our country.”

Duckworth is here today because she was kept alive through her “golden hour.” That’s what soldiers call the critical interval after a traumatic injury, when the bleeding is massive, shock sets in, and immediate action is necessary to save the downed soldier. In past conflicts, many American GIs spent their golden hours swirling to final oblivion in a morphine cloud. But now the military’s technology saves more injured troops, often leaving them to deal with a new, uncertain life at home.

Listening to Duckworth, it’s clear that she thinks America is in a golden hour of its own: The nation is reeling from an explosion of personal debt, unemployment, and health care costs, while conservatives, devoted to erasing deficits and cutting taxes for the rich, are letting the patient slip away. Duckworth believes urgent action is necessary. “I think we need to roll up our sleeves and stop fighting among ourselves,” she says. “We are facing some tough challenges. I think that we are still a leader of the free world…we certainly have a lot of work to do to take care of our people, but also to regain the previous spot that we had.” And no one, she believes, requires help more than the hundreds of thousands of Americans returning from a decade of war, desperately in need of services and, most of all, jobs.

Voters have long valued military experience in their political leaders. The number of vets in Congress is at a near-historic low—about 22 percent of the current group has served, versus 73 percent of House and Senate members in the early 1970s—yet is still three times greater than the percentage of Americans who are veterans.

But to get to Washington, Duckworth will have to beat an opponent who says her war record is only worth so much. After telling Politico last spring that he had “so much respect” for Duckworth’s sacrifice, Walsh went for the throat: “What else has she done? Female, wounded veteran…ehhh. She is nothing more than a handpicked Washington bureaucrat.” In July, he took another shot, suggesting at a campaign event that Duckworth—now a lieutenant colonel and a recipient of a Purple Heart, an Air Medal, and an Army Commendation Medal—should shut up about her service. “I’m running against a woman who, my God, that’s all she talks about,” he said. “Our true heroes, it’s the last thing in the world they talk about.”

IF BIOGRAPHIES ALONE WON elections, Ladda Tammy Duckworth might be a shoo-in. Her father, Franklin, was a World War II vet and lifetime NRA member who traced his lineage back to an ancestor who fought in the American Revolution. Her mother, Lamai, is a Thai woman of Chinese descent. Tammy was born in Bangkok in 1968 and grew up moving around Asia, where Franklin was working for the United Nations and multinational corporations.

While studying international affairs at George Washington University, Duckworth joined ROTC, which is how she met her husband, Bryan Bowlsbey, now a major in the Army National Guard. When they were both cadets, she said on C-SPAN in 2005, “He made a comment that I felt was derogatory about the role of women in the Army, but he came over and apologized very nicely and then helped me clean my M16.” The couple married in 1993.

Duckworth decided to fly helicopters because back then it was one of very few jobs with combat potential for women. She “got a lot of shit” as the first female platoon leader of her unit, she says. When she made her team cocoa before training exercises in the winter, the pilots took to calling her “mommy platoon leader.” “This is the military,” she says. “You find the person’s weakness, and you keep poking. They knew that I was hypersensitive about wanting to be one of the guys, that I wanted to be—pardon my language—a swinging dick, just like everyone else, so they just poked. And I let them, that’s the dumb thing.”

Duckworth’s unit was called to Iraq in 2004. That November 12, she was copiloting a Black Hawk with Milberg when insurgents lurking along the Tigris River launched a hail of small-arms fire. A rocket-propelled grenade exploded beneath the cockpit on the right side, directly under Duckworth. Milberg remembers the heat and force of the blast against his face. “I tried to make a mayday call, but the radio was dead,” he says. “Everything was dead.” Duckworth struggled mightily to reach the floor pedals, but the pedals—and her feet—were gone. Milberg fought the helo to the ground as Duckworth lost consciousness. “I immediately went to the other side and looked at Tammy,” he says, pausing to take a long breath. “I assumed at that point that she had passed. All I saw was her torso, and one leg on the floor. It looked like she was gone from the waist down.”

The next thing Duckworth knew, she was recovering from surgery at a Baghdad field hospital, minus two limbs. Soon she was sent to Germany and then on to Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, or the “amputee petting zoo,” as she liked to call it. “We had so many visitors,” she says, including Bush administration officials who were “there for the quick photo op.” But some showed a genuine interest, including former Sen. Bob Dole, who was injured in battle in WWII (and had been checked into Walter Reed for a slip-and-fall injury when Duckworth was there), and former Sen. Max Cleland, a triple amputee and decorated Vietnam War veteran.

Her home-state senator, Dick Durbin, soon learned about Duckworth’s presence on the ward. “It was kind of a running joke there among therapists,” he says. They would tell other soldiers in rehab, “C’mon, Tammy did it, you can do it.” The high-ranking Democrat invited her to Bush’s 2005 State of the Union address, where she arrived in her dress uniform—with an IV line concealed underneath. “I couldn’t believe how energetic this woman was,” Durbin says.

At a time when injured Iraq vets were starting to come home in droves, Duckworth’s can-do attitude made her a darling on the morning show circuit and earned her glowing write-ups in magazines like Glamour. Talk radio host Laura Ingraham called her “my new hero.” On the vets’ blog Blackfive, a commenter gushed, “A most admirable, intelligent, impressive individual, American Patriot, and lady! If she ran for political office, she has my vote! Gee, I hope she is Republican!” But no such luck: Duckworth declared her first candidacy for Congress in 2005 as one of the “Fighting Dems,” a cohort of vets aiming to seize the national-security mantle from the GOP.

Her Illinois district, the 6th, was narrowly divided, and Dole—who had dedicated his memoir, One Soldier’s Story, to Duckworth—endorsed her GOP challenger, Peter Roskam. There were dirty tricks: Some voters received a barrage of robocalls that sounded at the outset like they could have been from Duckworth’s campaign but in fact had been bankrolled by the National Republican Congressional Committee. (Voters who didn’t hang up quickly then heard an attack on her tax policies or other positions.) She lost her election by 2 points. “I sat in a bathtub and cried for three days,” she says.

THE DEFEAT DID NOT DAMPEN Duckworth’s ambition to serve. In addition to her ongoing service in the National Guard, she ran the Illinois veterans’ bureau from 2006 to 2009; when Obama took office he appointed her assistant secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs. She took an unvarnished approach. “I was all about admitting our failures,” she says. “I was frustrated the VA had been in this culture of hiding its problems.”

In both agencies Duckworth tackled the daunting challenge of reintegrating returning vets into the economy: As recently as last year, veterans aged 20 to 24 faced a whopping unemployment rate of 30 percent. As many as a quarter of vets suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, and up to a quarter may have suffered a traumatic brain injury. Suicide has been rampant: According to the Center for a New American Security, between 2005 and 2010 service members took their own lives approximately once every 36 hours. Nearly a million veterans who were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan are now readjusting to life on the homefront.

In Illinois, Duckworth pushed successfully for tax credits for businesses that hire vets with wartime service. Under Obama, she boosted services for homeless vets and created an Office of Online Communications, staffing it with respected military bloggers to help with troops’ day-to-day questions. Finally, in 2011, she resigned from the VA to make another run for Congress, in a more favorable 8th District redrawn last year by the Democratic-controlled Illinois Legislature. (Analysts have called the state’s new electoral map one of the biggest gerrymanders in modern memory; on his campaign stops, Walsh complains that the Democrats’ “road to Pelosi as speaker is through Illinois redistricting.”)

At first glance, Duckworth has an easy mark in incumbent Walsh, who upended a longtime Democratic congresswoman by a mere 290 votes in the tea party revolt of 2010. He hasn’t accomplished much legislatively: None of the 15 bills he has helped introduce—including plans to stop paying the United Nations, abolish scientific exploration of the North and South Poles, and deregulate milk prices—has made it out of committee.

But what Walsh has earned a name for is incendiary rhetoric: “They want the Hispanic vote; they want Hispanics to be dependent on government, just like they got African Americans dependent on government,” he yelled at a questioner during a meet-and-greet in May. At a town hall meeting in June, he called Obama a “tyrant,” then took it back, joking that the president “really isn’t smart enough to know what that means.” Walsh has also been in the spotlight over a lawsuit by his ex-wife alleging that the congressman failed to pay $117,437 in child support. (The parties settled privately this spring.)

But the election won’t hinge on Walsh’s antics—or Duckworth’s biography—alone. In the 8th District, riddled with half-vacant office parks and foreclosed homes, economic issues are sure to be voters’ prime focus. Duckworth’s response is that government has a key role to play: Her experiences in uniform and at the VA (and as the child of a vet who once had to rely on food stamps) convinced her of the importance of an effective social safety net. “My strength is in finding ways to make the government work for the people,” she says, “finding waste, or money that is not being properly used…or finding opportunities that are out there and making them work for the community.” As someone who is still paying down about $70,000 in student debt, Duckworth also wants to see more programs incentivizing national service in exchange for education benefits.

If conservatives once hesitated to attack her, it didn’t last long. At the VA, she found herself pulled into the death panels debate over an informational booklet titled “Your Life, Your Choices.” Fox News assailed Duckworth and accused the VA of telling injured vets to “hurry up and die.” Duckworth was unfazed, as she is by Walsh’s attacks on her military profile, which she brushes aside as a distraction from voters’ real concerns.

Then there’s the charge that Duckworth is a puppet of the Illinois political machine. She was appointed to the state veterans’ bureau by then-Gov. Rod Blagojevich, who’s now serving a 14-year prison term on corruption-related charges. She also has been in close contact with Chicago-based Obama advisers David Axelrod and Rahm Emanuel. “They’re certainly friends,” she says, adding that she runs some of her commercials by Axelrod before they air. As for Chicago’s mayor: “I think that Rahm Emanuel being willing to answer the phone when I call is a good thing for the district.”

Another vulnerability could be her decision to seek a degree from and endorse Capella University, an online for-profit school criticized for misleading veterans and treating them as a cash cow; a 2008 Department of Education audit found Capella had overcharged government lenders nearly $600,000 for student loans. “I absolutely welcome a full investigation into the for-profit schools, because I think a majority of them are predatory,” Duckworth says. “The schools that are truly rigorous would be able to meet any standard that’s set out there. I think Capella would make it.”

Although the 8th District leans blue, money could be a key factor against Duckworth. As of July, corporate campaign donations to Walsh—a venture capitalist and former policy director for the conservative Heartland Institute—eclipsed donations to Duckworth by a 14-1 margin. Walsh got a third of his money from PACs; his top donors include defense contractors, corporate lobbyists, and hedge funders. Nearly 90 percent of Duckworth’s donations came from individuals. In one effort to counter Walsh’s war chest, Duckworth boosted her funds with a July benefit concert by “the real Joe Walsh”—the Eagles singer—who is represented by the talent agency run by Rahm’s brother Ari Emanuel.

THE DUCKWORTH CAMPAIGN MOVES between events with military precision. The candidate rides shotgun in a young staffer’s SUV, hoisting herself into the seat with twitchy triceps and expertly disassembling her legs to save space, propping them at her side. On arrival, she reattaches the legs and clambers out as a staffer grabs a lightweight wheelchair from the cargo bay, often bringing along a barstool that Duckworth sits on during long meet-and-greets. A volunteer works Illinois’ 8th District, seen as key for Democrats to retake Congress.

A volunteer works Illinois’ 8th District, seen as key for Democrats to retake Congress.

Candidates have to walk, stand, talk, shake hands, answer questions, smile a lot, and rinse and repeat at a grueling pace. When Duckworth first got her new legs she could barely walk, and she couldn’t sit for more than a few hours at a time. Even now, you can read the weariness on her face. Taking a step with her right leg, the one that’s gone up to the hip, is like “trying to control a broom by holding on to the last two inches of the broom handle,” as she’s put it. She flings her hip into each pace. A grass median becomes a hazard. So do cracks in the sidewalk. And these days there are lots of cracked sidewalks in suburban Chicago.

This particular weekend has been jammed with campaign events—breakfast with organizers of a political action committee, a meet-and-greet at a barbecue restaurant, a small-donor fundraiser at a teacher’s house—but Duckworth insists on a final stop: a summerfest in the elm-lined burg of Villa Park. Bruce Springsteen’s “Pink Cadillac” echoes off brick storefronts, and there are bounce houses and bratwursts and World’s Greatest Dads cranking out balloons. The candidate rolls along in her wheelchair, stopping to buy trinkets and posing for pictures with the occasional vet. As dusk settles in, Gaelic tones blast from a sound system. “Trinity Irish Dancers!” Duckworth exclaims, zooming ahead. “I’m short. We’re gonna try to get up close to the stage.”

Her exhausted handlers hang back as she finds her place near the front amid a sea of squirming kids. Gradually, their attention turns away from the shiny-costumed, bewigged adolescents who are performing and toward the lady in their midst. Some approach to peer at her prosthetics. Don’t stare, one parent mouths to her son. I recall one of the workout shirts Duckworth told me she wants to wear in public but thus far hasn’t been allowed to by her advisers: “Wanna touch it?”

The wheelchair lady doesn’t acknowledge the gawkers; she’s busy staring at the kids onstage. All the motion in their dance is below the waist, in the hips, the knees, the ankles. She watches them turn out their toes, flutter their feet, and hop up and down. After several minutes of this Duckworth turns her wheelchair around and rolls out through the crowd, murmuring “excuse me” and “thank you” and “sorry” a dozen times over.

It’s not that she makes it all look easy; it’s that she keeps doing it. “I’m not so sure I could be such a good sport,” her mentor Quigley tells me. And he already is a congressman.

A week after the votes are counted in November, Duckworth will be headed for her alive day gathering in St. Louis. Chief Warrant Officer Milberg already has sent out the invitations to the crew. “I’m proud to be affiliated with a group that epitomizes the military spirit like they do,” Milberg says—and none more so than Duckworth, whose politics, he notes, generally don’t align with those of her crewmates. “I look at her and I think: ‘What have I got to be cryin’ about?'”

Perhaps after St. Louis she’ll be headed for Washington. “Her heart is in public service,” says Durbin, the party’s second in command in the Senate. “And when she walks onto that House floor, as a disabled woman veteran, speaking for a lot of Americans who aren’t well-enough represented, it will be a spectacular moment.”