Anti-abortion protesters surround a clinic in Huntsville, AlabamaSarah Cole/AP

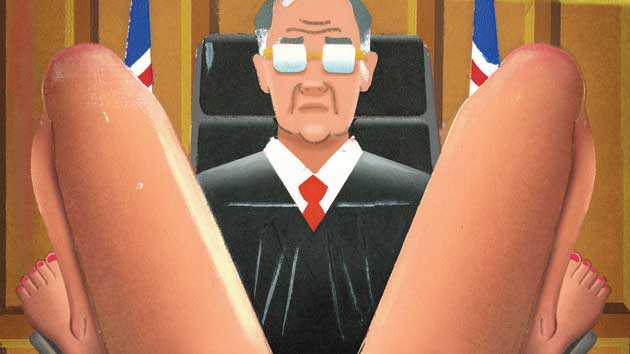

This spring, Alabama Republicans passed an extreme new law that would force minors who want to have an abortion without a parent’s permission to undergo a grueling court trial—and it would give judges the right to appoint a lawyer for the fetus. Last week, the American Civil Liberties Union asked a federal court to block the law, prompting national headlines.

But years before Alabama passed this new law, some state judges were already appointing lawyers for fetuses. The results weren’t pretty.

In Alabama, a minor who wants an abortion must have permission from a parent. The Supreme Court has ruled that states with such parental involvement requirements have to provide an out for young women who fear abuse or have have cut off contact with their parents. Alabama, like 36 other states, allows a minor to ask a judge for permission instead. The process, known as a judicial bypass, is meant to be swift, non-confrontational, and strictly confidential.

Alabama’s new law sets up time-consuming inquisitions. It requires district attorneys to cross-examine minors who want an abortion without parental approval, and it allows DAs and lawyers for fetuses to call witnesses to testify against the pregnant girls. Under this measure, a judge can adjourn bypass hearings for long periods of time, and a judge can disclose the minor’s identity to any person who “needs to know.” If a minor’s parents become aware of a bypass hearing—which the Supreme Court intended to be confidential—the law allows the parents to participate in the hearing and be represented by a lawyer.

In other words, Alabama’s law is unprecedented. But the practice of appointing attorneys to represent fetuses in judicial bypass hearings is not. An Alabama judge tried to appoint representation for a fetus in the state’s very first bypass hearing in 1987. A 1988 Ms. cover story on that case reported that the judge, Charles Nice, reassigned an attorney who wanted to represent the minor to represent the minor’s fetus instead. The attorney refused to cooperate, and Judge Nice dropped the idea.

State Judge Walter Mark Anderson III revived the controversial practice in later cases. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, he appointed attorney and local pro-life leader Julian McPhillips to represent fetuses in nearly every one of the dozens of bypass hearing held in his court. A 1999 article in the Nation recounted how McPhillips cross-examined a 17-year-old girl. The minor was seeking an abortion in secret, she testified, because her father often pointed his gun at boys who seemed interested in her. McPhillips named the seven-week-old fetus “Baby Ashley.”

McPhillips: You say that you are aware that God instructed you not to kill your own baby, but you want to do it anyway? And are you saying here today that notwithstanding everything that you want to interfere with God’s plan for your baby?

Minor: I think that is between me and God.

McPhillips: And you are not concerned after you have had the abortion that some day you may wake up and say my gosh, what have I done to my own baby?

Minor: It may happen.

McPhillips: You are not worried about being haunted by this? Here you have the chance to save the life of your own baby…. And still you want to go ahead and snuff out the life of your own baby?

Minor: Yes.

I spoke to Anderson, who is no longer on the bench, this spring. The former judge recalled that McPhillips often called witnesses to testify against minors in bypass hearings. McPhillips brought in doctors to testify that abortion was medically risky, and called as witnesses women who had abortions in the past and come to regret the procedure. “I’ll never forget one lady who testified,” Anderson said, “She said, ‘I wish that somebody had protected my baby.'”

In the case of “Baby Ashley,” Anderson ruled that the minor was mature enough to decide on her own to have an abortion. McPhillips appealed that decision on behalf of the fetus. The Alabama Court of Civil Appeals ruled that a fetus couldn’t appeal.

But appeals court didn’t prevent other judges from appointing attorneys for fetuses in the future. After the “Baby Ashley” case, Anderson told me, two other Alabama judges followed Anderson’s example and began appointing fetal attorneys in all their bypass hearings. A trial judge in Florida implemented the practice in a 1999 bypass hearing of a 16-year-old girl; the fetal attorney dubbed his “client” “Baby Teresa.”

Julianna Taylor, a Montgomery, Alabama, attorney who represented many minors pro bono, recalls that lawyers for fetuses would “give these hypotheticals: ‘What if I could promise you that this child is going to have a beautiful, happy life with a loving adopted family? Would you kill a child that was already one year old?’ Really? Here you are making a huge decision, a huge decision for a teenager, probably the biggest decision that they’d ever have to make, and you’re going to ask them questions like that?”

Anderson kept appointing lawyers for fetuses until 2004, when he and the judges who had followed his lead lost their reelections for reasons unrelated to the bypass hearings. Anderson didn’t know that the idea he pioneered had become law until I told him this spring. “That’s fantastic!” he exclaimed.