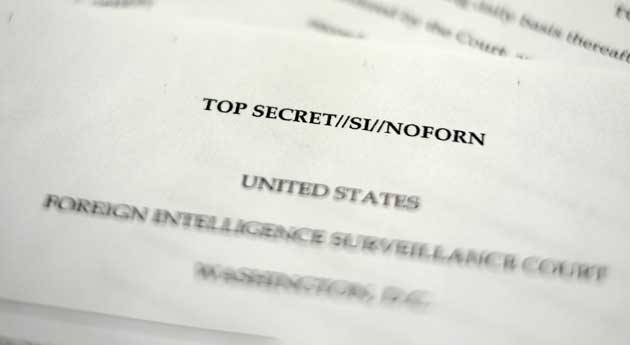

A copy of the US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court order requiring Verizon to give the National Security Agency (NSA) information on all landline and mobile telephone calls in its systems. Associated Press/AP

When the USA Freedom Act was passed last week, it was hailed as the first major limit on NSA surveillance powers in decades. Less talked about was the law’s mandate to open a secret intelligence court to unprecedented scrutiny.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, often known as the FISA court after the 1978 law that created it, rules on government requests for surveillance of foreigners. Its 11 federal judges, appointed by the chief justice of the Supreme Court, consider the requests one at a time on a rotating basis. In closed proceedings, they have approved nearly every one of the surveillance orders that have come before the court, and their rulings are classified.

Privacy advocates say those secret deliberations have created a black box that keeps the public from seeing both why the government makes key surveillance decisions and how it justifies them. But the new law passed by Congress last week may shed some new light on these matters. “The larger step that the USA Freedom Act accomplishes is that it is bringing those things out to the public,” says Mark Jaycox, a legislative analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital privacy advocacy group. The new law mandates that FISA court rulings that create “novel and significant” changes to surveillance law be declassified—and it is up to the judges to determine if the cases reach that threshold—though only after review by the attorney general and the director of national intelligence. While FISA court rulings have been leaked and occasionally declassified, the new law marks the first time Congress has attempted to make the court’s decisions available to the public.

The law also requires the court to create an advisory panel of privacy experts, known as an amicus panel. When a judge considers what she considers a “novel or significant” cases, she will call on that panel to discuss civil liberties concerns the surveillance requests brings up. Judges can also use the panel in other cases as they see fit.

The USA Freedom doesn’t lay out how the amicus panel will work in detail. But privacy advocates say its mere existence will be an important step. “We know we will see the order and potentially that an amicus [a privacy panel member] is going to be there arguing against it. Those things are huge to us,” Jaycox says.

But while the USA Freedom Act calls for important FISA court rulings will be made public, there’s no guarantee they will be. For one, final say on declassification still rests with the executive branch rather than the judges themselves.

And while the judges’ input on the cases will still be important—if not final—says Liza Goitein, co-director of the Liberty and National Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice, they have already shown a “sort of reflexive deference” to the government.

In fact, advocates say, judges have always had the powers outlined in the new law—to bring in consultants or recommend declassifying their opinions. “This is something the FISA court could have done all along,” says Amie Stepanovich, the US policy manager for privacy advocacy group Access. “They always could have chosen to be more transparent in their proceedings.” Privacy advocates hope that having these pre-existing powers now written into law means that judges will actually use them, but even that isn’t for certain.

“I think the transparency provisions are going to be effective for the judges who are inclined to support them and are going to be ineffective for the judges who aren’t,” says Steve Vladeck, a professor at American University’s Washington College of Law.

There are other procedural moves the government could use to limit what information is made public. The court could simply issue summaries of decisions that don’t include their key parts, or the executive branch could heavily redact them. “In theory, the executive branch could comply with this part of the statute by redacting 99 percent—everything but one sentence, essentially—of an opinion,” Goitein says.

She admits that specific tactic is unlikely—it would be an obvious and public skirting of the law’s intent—but stresses that even though the law makes important progress in disclosure, there are still many loopholes that could cut down on how much the public will get to see.

“I think the history strongly suggests that the intelligence establishment will take every single little bit of rope it has,” she says. “And then some.”