Sometime in the late 1970s, after he’d divorced his college sweetheart, had a kid with another woman, lost four statewide elections, and been evicted from his home on Maple Street in Burlington, Vermont, Bernie Sanders moved in with a friend named Richard Sugarman. Sanders, a restless political activist and armchair psychologist with a penchant for arguing his theories late into the night, found a sounding board in the young scholar, who taught philosophy at the nearby University of Vermont. At the time, Sanders was struggling to square his revolutionary zeal with his overwhelming rejection at the polls—and this was reflected in a regular ritual. Many mornings, Sanders greeted his roommate with a simple statement: “We’re not crazy.”

“I’d say, ‘Bernard, maybe the first thing you should say is “Good morning” or something,'” Sugarman recalls. “But he’d say, ‘We’re. Not. Crazy.'”

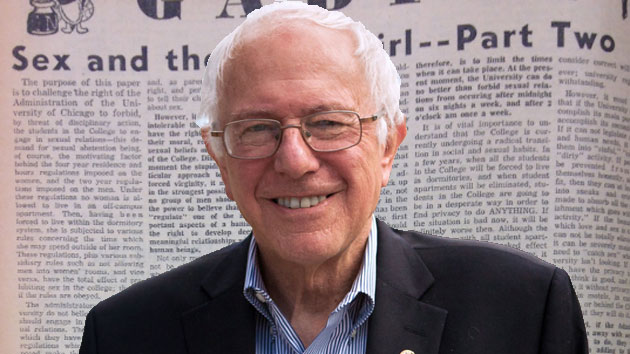

Sanders eventually got a place of his own, found his way, and in 1981 was elected mayor of Burlington, the state’s largest city—the start of an improbable political career that led him to Congress, and soon, he hopes, the White House. In May, after more than three decades as an independent socialist, the septuagenarian senator launched his campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination in the Vermont city where this long, strange trip began.

The 2016 election is a homecoming for Sanders in another sense. He’s returning to the role he embraced during his early years in politics—that of the long shot. In Hillary Clinton, with her lengthy CV, vast donor network, and unmatched name recognition, he could hardly have picked a tougher target. But those same qualities also position Sanders, a lifelong critic of war hawks, Wall Street, and the ruling class, to exploit the angst among progressives who spent much of the last year pining for Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) to run instead.

Sanders wants to break up the biggest banks, double the minimum wage, and put the entire country on Medicare. And his message has been resonating. He’s drawn massive crowds nearly everywhere he’s traveled. In August, 28,000 people showed up to see him speak at an arena in Madison, Wisconsin. Two recent polls have put him ahead of Clinton in New Hampshire. Bernie-mentum—as the pundit class has dubbed the candidate’s surging appeal—has the Clinton camp worried that Sanders defeat her in Iowa, according to the New York Times. Indeed, a September poll showed Sanders edging out Clinton by 10 points there.

Much of the enthusiasm for his candidacy is coming from college students and true believers who think the party establishment has been compromised. That was true of Barack Obama. It was also true of Ron Paul. Sanders’ success will hinge on how much he can broaden his base beyond that comfort zone. Already he’s become a frequent target of Black Lives Matter activists, who have argued that his ambitious platform for taking on economic inequality does not do enough to address the structural racism—in criminal justice, housing, and beyond—that perpetuates the prosperity gap. (Not long after a Seattle event was shut down by protestors, Sanders did unveil a racial justice platform.) If Sanders continues to perform as well as the polls suggest and he maintains his momentum through the upcoming debates, he might just inch the entire party, if not the country, just a few steps closer to Norway.

Which, if you think about it, does sound kind of crazy. But if Sanders had the audacity to think he might stay in the ring long enough to pull together a genuine movement, it might be because he’s done it before. Sanders’ early years offer a blueprint for how a self-described socialist can, with the right breaks and enough persistence, make it in electoral politics. He didn’t emerge into a national political force overnight. He almost never made it at all. In Vermont he discovered it wasn’t enough to hold lofty ideas and wait for the revolution; he had to learn how to play the political game.

Born in Flatbush, Brooklyn, Bernie Sanders grew up in a working-class family. His father, a Polish immigrant whose family largely perished in the Holocaust, sold paint; his mother died when he was 18. When Sanders was a teen, his older brother, Larry—now an aspiring progressive politician in the United Kingdom—introduced him to Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. By the time Sanders graduated from high school, where he ran for class president (and lost) on the promise of granting scholarships to Korean refugees, his political course was set.

The University of Chicago campus Sanders arrived on in the fall of 1961, after one year at Brooklyn College, would never be confused with Berkeley circa 1969, but in spite of its stodgy reputation it was fertile ground for liberal activists. Future Weather Underground cofounder Bernardine Dohrn was a year ahead of Sanders; Malcolm X came to campus to speak during his sophomore year.

Sanders’ roommate in Chamberlin House, a Gothic building that evokes comparisons to Hogwarts, was a student named David Reiter, a disciple of the conservative economics professor Milton Friedman. They entered into fierce debates over socialism, but Sanders could never let the argument rest. “I went to bed, but I have a vivid memory of him just sitting there, shaking his head sadly,” Reiter says. “He was so sad that I just couldn’t understand what was wrong with the free market. It was more in sorrow than in anger.”

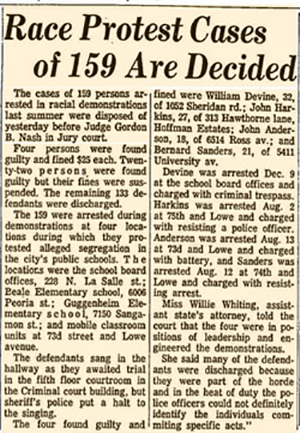

During Sanders’ first year in Chicago, a campus scandal erupted when an interracial group of students uncovered systematic housing discrimination in university-owned apartment buildings. Apartments that were open to white students mysteriously went off the market when black students came to inquire, and then just as quickly opened up again. Sanders, a chapter leader of the Congress of Racial Equality, the civil rights group that organized the Freedom Rides, helped to launch a sit-in at the office of the university’s president, aimed at ending the practice. After 15 days, CORE worked out a compromise with the administration—it would vacate the premises if the university included representatives from CORE in a new commission to study the housing issue. It was the first of many begrudging deals with the establishment he was fighting against. (When the journalist Rick Perlstein brought up the subject of CORE’s compromise on the housing issue in a recent interview, the senator issued “a weary sigh.”) Off campus, Sanders led a picket of a segregated restaurant, attended the 1963 March on Washington, and was arrested for protesting outside a segregated school.

He was, by his own admission, “not a good student.” Instead of studying for his political science classes, he preferred spending long hours pursuing his own interests—the Spanish Civil War, political philosophers including Marx and John Stuart Mill, and psychologists such as Freud and his disciple, Wilhelm Reich—and generally raising hell. A 2,000-word manifesto he penned for the student newspaper, attacking the administration’s strict sex-segregated housing guidelines as “fornication of the Bible and Ann Landers,” triggered a campus debate on free love that made national news. That crusade was classic Sanders: firm in his beliefs, fiery in his rhetoric, and unafraid of confrontation. It also failed. In that sense, it was an appropriate lesson for a young activist who would go on to spend most of his life as an outsider: Change takes time.

Sanders’ independent streak was evident in his choice of student groups. He joined the Young People’s Socialist League (“Yipsel”), an organization that advocated the “social ownership and democratic control of the means of production and distribution” but was explicitly anti-communist. This put the group in an awkward position—too far left for the Democrats, too far right for the true radicals. Sanders, like many Yipsel members, also became involved in the pro-disarmament Student Peace Union, which shared the organization’s alienation from Cold War politics. “They had a kind of stern independence,” says Todd Gitlin, a Columbia University sociologist who was an early leader in Students for a Democratic Society, another Yipsel-influenced group. “They regarded themselves as ‘third campers’—they didn’t want to be identified with either the West or the Soviet bloc, and in that way they were at odds with the remnants of the Communist Party and fellow travelers.” And unlike many contemporary groups, activists of Sanders’ ilk believed the path to revolution passed through traditional institutions. “There was a feeling about them that they were sort of pros, they took politics seriously,” Gitlin says. “They were the anti-utopians. They were impatient about fancy as-if thinking and sort of hard-headed about who to reach.”

Sanders and his fellow 1960s radicals did have one thing in common, though. They all seemed to want to move to Vermont.

Fresh from a stint on an Israeli kibbutz, Sanders arrived in Vermont in 1964 on the crest of a wave. The state’s population jumped 31 percent between 1960 and 1980, due largely to an infusion of more than 30,000 hippies. It was a retreat, in the most literal sense, from the clashes over the Vietnam War and civil rights that had defined their college years. But there was a political subtext to the move as well. A seminal essay authored by two Yale Law School students called the “Jamestown Seventy” called for the “migration of large numbers of people to a single state for the express purpose of effecting a peaceful political takeover of that state through the elective process.” Sanders and his first wife bought 85 acres outside of Montpelier for $2,500. The only building on the property was an old maple-sugar shack without electricity or running water that Sanders converted into a cabin.

Free-range hair and sandals notwithstanding, Sanders never quite fit the mold of the back-to-the-landers he joined. “I don’t think Bernie was particularly into growing vegetables,” one friend put it. Nor was he much into smoking them. “He described himself once in my hearing as ‘the only person who did not get high in the ’60s,'” recalls Greg Guma, a writer and activist who moved in the same circles as Sanders. “He didn’t even like rock music. He likes country music.” (Sanders recently revealed that he has smoked marijuana twice.) “He’s not a hippie, never was a hippie,” Sugarman says. “But he was always a little bit on the suburbs of society.”

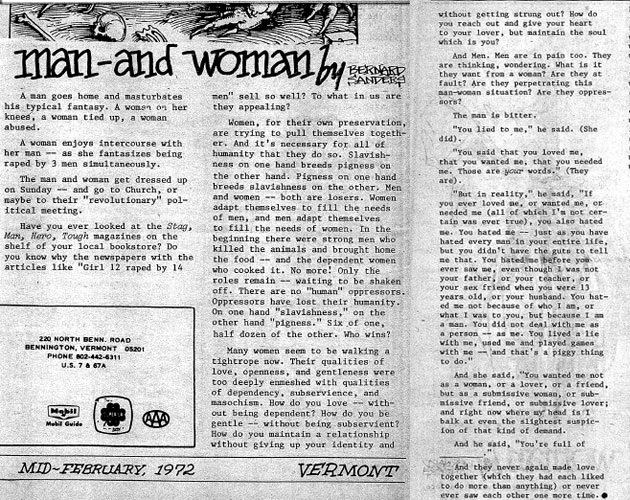

What Sanders shared with the young radicals and hippies flocking to Vermont was a smoldering idealism, but only a fuzzy sense of how to act on it. Sanders bounced between Vermont and New York City, where he worked at a psychiatric hospital and studied at the New School for Social Research. After his marriage broke up in the late 1960s, he moved to an A-frame farmhouse outside Stannard, a tiny Vermont hamlet with no paved roads in the buckle of the commune belt. He dabbled in carpentry and tried to get by as a freelance journalist for alternative newspapers and regional publications, contributing interviews, political screeds, and, one time, a stream-of-consciousness essay on the nature of male-female sexual dynamics. “A woman enjoys intercourse with her man—as she fantasizes being raped by 3 men simultaneously,” Sanders wrote in one eyebrow-raising passage that recently caused controversy for his presidential campaign after Mother Jones reported on the essay.

Sanders’ politics were deeply influenced by what he learned about human psychology. Leaning heavily on the work of Reich, he wrote an essay arguing that cancer was caused by sexual frustration—which in turn was a product of bad parenting and a suffocating public school system. He criticized water fluoridation as a government intrusion on individual freedom. And, citing Freud, he elaborated on a theory of a worldwide “death instinct,” in which “the human spirit has been so crushed by the society in which it exists, that the general will toward life is not very strong.”

The way out, he believed, required a dramatic upheaval of cultural norms. “The Revolution is coming and it is a very beautiful revolution,” he wrote in 1969. “It is beautiful because, in its deepest sense, it is quiet, gentle, and all pervasive. It KNOWS. What is most important in this revolution will require no guns, no commandants, no screaming ‘leaders,’ and no vicious publications accusing everyone else of being counter-revolutionary. The revolution comes when two strangers smile at each other, when a father refuses to send his child to school because schools destroy children, when a commune is started and people begin to trust each other, when a young man refuses to go to war, and when a girl pushes aside all that her mother has ‘taught’ her and accepts her boyfriend’s love.”

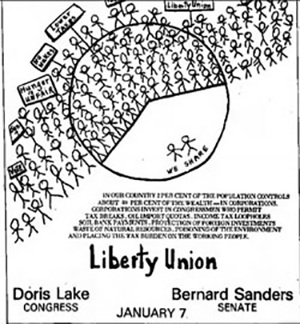

Sanders had been adrift in his own ideas, until he discovered the Liberty Union Party, which had been conceived in 1970 to uproot the two-party system and end the Vietnam War. In Vermont, its leaders hoped to find a receptive audience amid the hippie newcomers. Its cofounder, a gruff, bushy-bearded man named Peter Diamondstone, had predated Sanders at the University of Chicago by a year; Diamondstone likes to joke that they “knew all the same Communists” on the South Side.

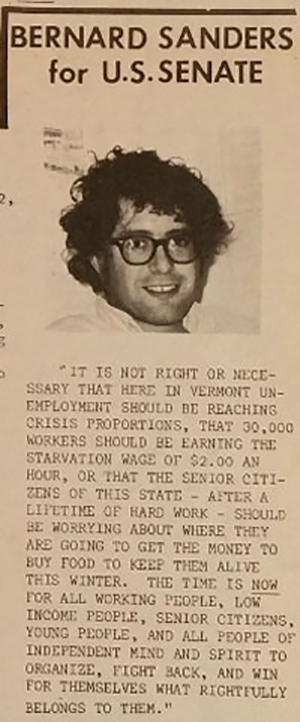

By the fall of 1971, Liberty Union was floundering. “We were lost as a political party,” Diamondstone says. That October, Sanders, who had done some speechwriting for one of the party’s candidates a year earlier, showed up with a friend at the Goddard College library for a Liberty Union meeting. It was a large crowd by the group’s standards—maybe 30 people. The party was struggling to field a candidate for the upcoming Senate special election. Sanders, with dark hair, thick black glasses, and his two-year-old son in his arms, stood up impulsively in a room full of strangers. “He said, ‘I’ll do it—what do I have to do?'” Diamondstone recalls.

Sanders lost that race, the first of four losing campaigns over the next five years (two for Senate, two for governor). In addition to opposing the war, the party pushed for a guaranteed minimum wage and tougher corporate regulations. Sanders floated hippie-friendly proposals, such as legalizing all drugs, an end to compulsory education, and widening the entrance ramps of interstate highways to allow cars to more easily pull over to pick up hitchhikers.

He emerged as one of the organization’s leading voices and within a few years was named Liberty Union’s chairman. “He was a mouthpiece, he was an orator—we called him ‘Silvertongue,'” Diamondstone says. During his 1972 campaign for governor, Sanders crisscrossed the state with the party’s choice for president—the child-rearing guru Dr. Benjamin Spock.

In those early years, Sanders was a true believer in what might be called small-s socialism, and he had little patience for lukewarm allies. He believed in the need for a united front of anti-capitalist activists marching in step against the corrupt establishment. Greg Guma recalled meeting Sanders for the first time and asking why he should get his vote. Sanders, in effect, told Guma that if he even needed to ask, Liberty Union wasn’t for him. “Do you know what the movement is? Have you read the books?” he recalled Sanders responding. “If you didn’t come to work for the movement, you came for the wrong reasons—I don’t care who you are, I don’t need you.”

In interviews at the time, Sanders suggested that dwelling on local issues was counterproductive, because it distracted activists from the real root of the problem—Washington. “I once asked him what he meant by calling himself a ‘socialist,’ and he referred to an article that was already a touchstone of mine, which was Albert Einstein’s ‘Why Socialism?’” says Sanders’ friend Jim Rader. “I think that Bernie’s basic idea of socialism was just about as simple as Einstein’s formulation.” (In short, according to Einstein, capitalism is a soul-sucking construct that corrodes society.)

Sanders started a small monthly zine called Movement to promote Liberty Union’s agenda and the countercultural lifestyles of its supporters. He devoted one lengthy article to an interview with a friend who had recently given birth at home. (“Don’t all mammals eat the afterbirth?” Sanders asked in one leading question.)

Sanders built his campaigns around a theme that would sound familiar to his supporters today: American society had been hijacked by plutocrats, prudes, and imperialists, and wholesale reform was needed to restore it to its rightful course. “I have the very frightened feeling that if fundamental and radical change does not come about in the very near future, that our nation, and, in fact, our entire civilization, could soon be entering an economic dark age,” he said in announcing his 1974 Senate bid. Later that year, he sent an open letter to President Gerald Ford, warning of a “virtual Rockefeller family dictatorship over the nation” if Nelson Rockefeller were named vice president. He also called for the CIA to be disbanded immediately, in the wake of eye-popping revelations about the agency’s misdeeds.

But Sanders began to question whether Liberty Union had a future. Although the party had, at his direction, attempted to broaden its base by aligning itself with organized labor and the working poor, he drew just 6 percent of the vote when he ran for governor in 1976 (his previous three campaigns hadn’t fared any better). He was drifting from the utopian ambitions of Diamondstone, who was now advocating “a worldwide socialist revolution.” After the last American troops left Saigon in 1975, the anti-war party faced an existential crisis. And Sanders faced one of his own. Liberty Union could claim a few victories—it had helped to defeat a telephone rate increase, among other things. But he believed that, absent a serious change, the party would be nothing more than symbolic.

“That’s what distinguished [Sanders] from leftists who were more invested in the symbolism than in the outcome,” Sugarman says. “He read Marx, he understood Marx’s critique of capitalism—but he also understood Marx doesn’t give you too many prescriptions of how society should go forward.”

Sanders had reason for introspection. Once again single and helping to raise a young son, he was struggling financially—a newspaper article during his 1974 race noted that he was running for office while on unemployment. Increasingly, Sanders’ political gaze focused on his own backyard.

Meanwhile, Sanders and Diamondstone clashed about the direction of Liberty Union—and pretty much everything else. “When I was on the road, I would stop at his house and I’d sleep downstairs, and we’d yell at each other all night long, and sometime around three o’clock in the morning, we’d say, ‘We gotta stop this,’ so we could get some sleep,” Diamondstone recalls. “Five minutes later we’d be yelling at each other again.”

Sanders quit the party in 1977, and his relationship with Diamondstone continued to deteriorate; when Sanders campaigned for Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale in 1984, Diamondstone followed him to every campaign stop, handing out leaflets calling the then-mayor a “quisling.”

After cutting his ties with Liberty Union, Sanders remained as confident as ever of the need for radical change in the nation’s power structure, if less sure of how to get there. First, he had to get his life in order. “He was living in the back of an old brick building, and when he couldn’t pay the [electric bill], he would take extension cords and run down to the basement and plug them into the landlord’s outlet,” says Nancy Barnett, an artist who lived next door to Sanders in Burlington. The fridge was often empty, but the apartment was littered with legal pads filled with Sanders’ writings. When he was eventually evicted, Sanders moved in with his friend Sugarman.

“The fact that neither of us could afford to live in the city where we worked was a source of great consternation to us and I think the beginning of a [mayoral] platform, honestly,” Sugarman says of their roommate days.

Sanders kept busy building a company he had started with Barnett called the American People’s Historical Society, which produced filmstrips for elementary school classrooms on topics including women in American history and New England heroes. It was a DIY operation—Sanders did the male voices, Barnett the female ones. The work took them up and down New England’s back roads, as they sold copies of the filmstrips to school administrators. “His cars were always breaking down,” Barnett says. “He was extremely frugal.” In one of his jalopies, Sanders (or one of his passengers) had to clear the windshield manually using the wiper blade he kept in the glove compartment.

Sanders channeled his earnings from the educational films into his pièce de résistance: a documentary on the life of union leader Eugene Debs, who won nearly a million votes running for president from prison on the Socialist ticket in 1920.

“We had gone to New York and lined up Howard Da Silva, who was a big Broadway booming voice actor, to play Eugene Debs’ voice,” Barnett explains. “But that didn’t quite work out, so Bernie ended up doing the narration of Debs’ voice.” Bernie Sanders is from Brooklyn; Debs was not. The movie also suffered from the filmmaker’s reverence for his subject. Sanders, one reviewer opined, seemed “determined to administer Debs to the viewer as if it were an unpleasant, but necessary, medicine.”

When Sanders tried to get the documentary aired on public television in 1978, he was rebuffed. Fearful perhaps that even humble Vermont Public Broadcasting had fallen under the dominion of corporate media, Sanders cried censorship and fought back. Eventually, the Debs documentary was broadcast. “That was a breakthrough of sorts,” Sugarman says. “That was actually our first successful fight.”

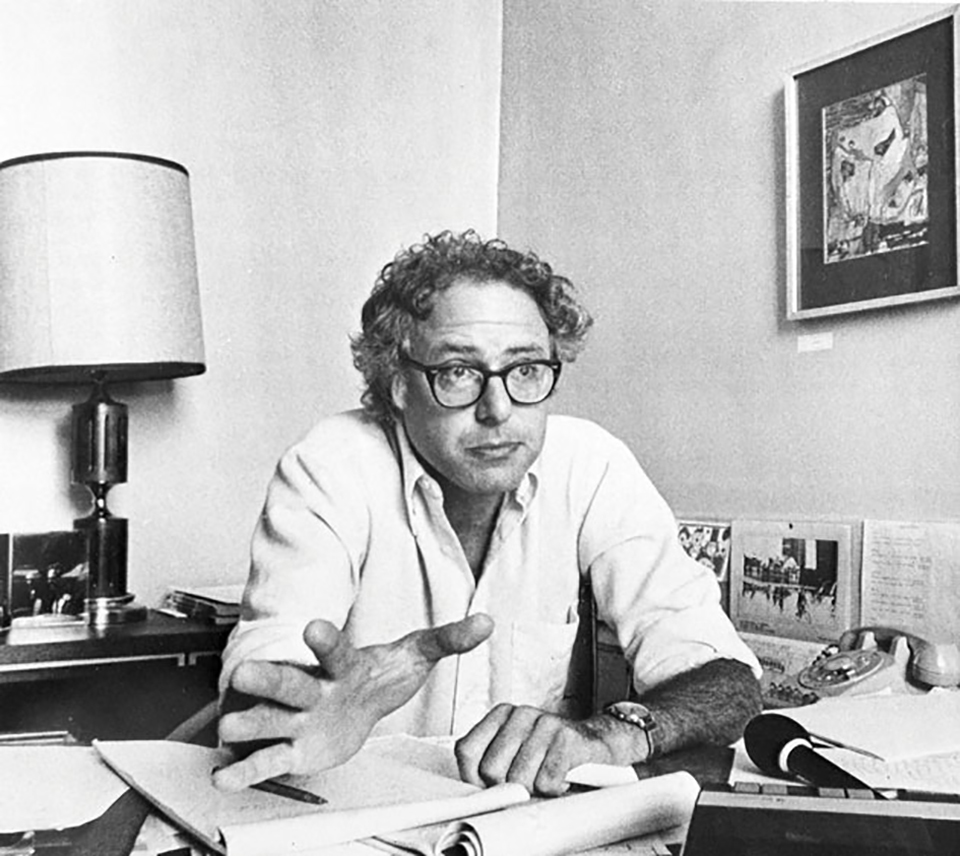

Not long after making the Debs documentary, Sanders got back in the political game. He ran for mayor of Burlington in 1981 as an independent, and he crafted a hyperlocal platform that cut across party lines—he opposed a waterfront condominium project, supported preserving a local hill for sledding, and pushed to bring a minor league baseball team to town. Sanders was still, at heart, the same neurotic activist who picked fights with Diamondstone over socialism, but he recognized that voters in Burlington wanted to hear what he thought about Burlington.

At first, no one gave Sanders a shot. He focused on building support in Burlington’s poor and working-class neighborhoods, where voters felt forsaken by the longtime Democratic incumbent, Gordon Paquette. From there, he assembled a surprisingly broad coalition, even winning the endorsement of the local police union. To everyone’s surprise, he knocked off Paquette by 10 votes out of 8,650 cast. After a decade on the outside, Sanders finally had a foot in the door—and a steady job. “It’s so strange, just having money,” he told the Associated Press at the time.

As Burlington’s mayor, and later as a US representative and senator, Sanders has followed a similar formula. He’s unafraid to raise hell about the corporate forces he fears are driving America into the ground—replace “Rockefeller” with “Koch” and his Liberty Union speeches don’t sound dated—but always careful to keep Vermont in his sights. The days of meandering psychoanalytic cultural critiques are mostly over. And while he’s running on a platform that includes some pretty radical ideas for Washington—single-payer health care; free college; 50-percent-plus income tax rates for America’s top earners—at times, Sanders has shown a willingness to compromise that’s disappointed longtime ideological allies. He has supported the F-35, Lockheed Martin’s problem-plagued fighter jet that has led to hundreds of billions of dollars in cost overruns; Burlington’s international airport was chosen as one of the homes for the planes. “He became what we call up here a ‘Vermont Exceptionalist,'” Guma says of the candidate’s pragmatic streak. Sanders has also drawn heat from the left over his libertarian-tinged position on gun control, which has at times allied him with his Republican colleagues, including in 2005 when he voted for a bill that shielded gun manufacturers from legal liability when their firearms are used by criminals.

Unlike his idol Debs, whose third-party campaigns earned him roughly the same percentage of the vote as Liberty Union’s first electoral forays, Sanders is now running within the Democratic Party. He has chosen, as he did many years ago, relevance over purity, to engage the system rather than escape it. He could hardly have picked a better time. On many of the issues he’s spent his career championing, Sanders no longer sounds so fringe. The party’s progressive wing rebelled in May over President Obama’s Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the most polarizing free-trade deal since NAFTA (which, naturally, Sanders voted against). The $15 minimum wage is the hottest new trend in municipal governance. Billionaire donors are forming their own de facto shadow parties. Income inequality has become so pronounced even Republicans are talking about it.

Despite his impressive momentum, the national polls of the presidential race still give Clinton a sizable lead over Sanders. But they also put him squarely in second place, well ahead of former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley. Sanders has signaled that Clinton’s early support for the Iraq War—which first created an opening for Obama in 2007—will be fair game during the race. He’s jabbed the former secretary of state for her ambiguous stance on the TPP. And in a nod to the Clintons’ deep pockets (and even deeper-pocketed donors), Sanders has warned that his rival is not “prepared to take on the billionaire class” that he believes is a driver and beneficiary of income inequality.

He’s also learned the risks of being taken seriously. The Clinton campaign has already showed its willingness to take the gloves off. In June, Hillary-backer Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.) suggested that reporters were “giving Bernie a pass” on his socialist roots and argued that he’d fall back to Earth once people started to treat him “like a serious candidate.” Even as Sanders bounced from one overflow crowd to the next (3,000 in Minneapolis; 2,500 in Council Bluffs, Iowa), he spent much of the first week of his campaign explaining away that 1972 essay on gender norms. It was, he ultimately told NBC’s Meet the Press, a piece of “fiction,” along the lines of Fifty Shades of Grey. It wasn’t the splash the campaign hoped to make, but the real news was that the story was news at all; cable news never went into overdrive over Dennis Kucinich’s early years.

Sanders is now standing on the biggest platform of his political career. Win or lose, his ideas will influence the national debate as never before. In some ways they already have. In August, the Democratic National Committee adopted a $15 minimum wage as part of its official platform, bringing the senator’s once-radical proposal firmly into the mainstream. Sanders always seemed to know that he’d get his chance to effect big change, even if others dismissed him as a radical or derided him as a socialist. Perhaps this was what he meant when he repeated those self-affirming words—”We’re not crazy”—to Richard Sugarman all those years ago. And if Sanders were to somehow defy the odds, he and Sugarman could be reunited in Washington. Sanders has promised his old friend, who still teaches at the University of Vermont, the same position he held during the mayoral years in Burlington—”Secretary of Reality.”