Terry Fulton put this sign outside his store last fall "to let people know they don’t have to worry about a mass shooting over here at Fulton’s tackle box."Tim Murphy

Michelle Wiles says her wake-up call came a few years back when she saw what Muslim immigrants had done to the small city of Hamtramck, Michigan, where her mother’s family is from. A small, historically Polish community almost entirely surrounded by Detroit, Hamtramck used to be filled with Christmas decorations in the winter. These days, she says—as we sit in the office of a biofuels company near her home in Spartanburg County, South Carolina, one evening in December—”that’s where they have blow horns.”

“Where they blast out their call to prayer,” she explains. “Which is, you know, to Allah.”

Wiles, who is a member of Texas Sen. Ted Cruz’s South Carolina leadership team, believes large portions of Michigan have already been transformed into a de facto Islamic state that’s off-limits to nonbelievers. “Just Google ‘Christians stoned by Muslims in Dearborn‘—there’s plenty of video,” she says. (I did, and I watched a group of beefy dudes with signs about “idolators” and “sodomites” being taunted by 14-year-olds.) Unless good Christian people take a stand, Wiles fears South Carolina might be next.

So last spring, she and a friend launched Secure Spartanburg County, a grassroots group dedicated to stopping refugees from resettling in the state. They’ve held meetings with policymakers about Syrian resettlement, hosted a conference on how to stop it, and worked with allies in a half-dozen counties to make their state as hostile as possible to refugees. And finally, it seems, her fellow Republicans are coming around.

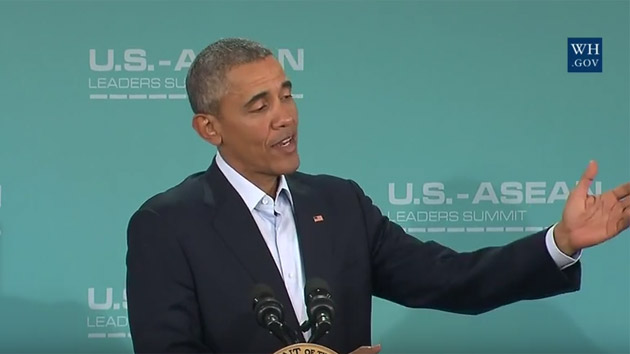

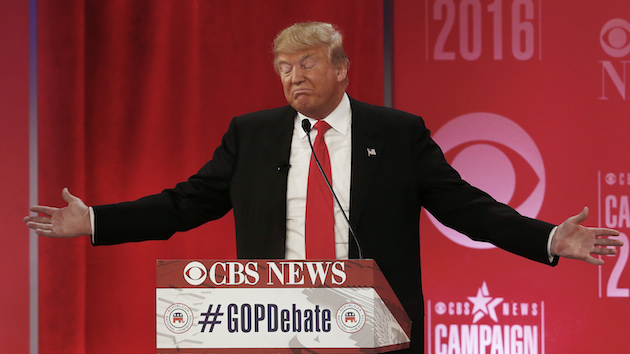

After the terrorist attacks last fall in Paris and San Bernardino, California, fears of an Islamist threat to the homeland went from the fringe to the forefront of the Republican primary and have stayed there ever since. According to NBC’s exit poll, 66 percent of voters in the recent New Hampshire Republican primary supported banning Muslims from the United States—and they handed Donald Trump a resounding 20-point victory. In South Carolina, where GOP voters seem poised to hand the real estate mogul another big win on Saturday, terrorism is the No. 1 concern of a majority of Republican voters, and Trump supporters have some ideas about what to do about it. Two-thirds of Trump backers support a federal registry of Muslims; only 44 percent believe Islam should even be legal. Cruz, who is Trump’s closest competition, has proposed a moratorium on accepting refugees from predominantly Muslims countries. Together, they have more support in South Carolina than the other four candidates combined.

Trump’s nativist protectionism and Cruz’s religious Constitutionalism made them favorites to win the state long before the attacks in Paris. But in zeroing in on Muslim refugees, they tapped into an issue that has been burning up the party’s grassroots for a long time. Local activists such as Wiles began fighting state and federal authorities to stop the flow of Muslim refugees nearly a year ago, long before national Republicans discovered the issue in the fall. Every year since 2011, conservative lawmakers have pushed to ban Islamic Shariah law from being applied in state courts. Activists have even complained that one rural corner of the state is already under Islamist control.

“One of the CNN reporters called me right after [Trump] made that announcement [of his proposed Muslim ban] and asked me ‘what do you really think of this policy?'” recalled Will Folks, who runs the South Carolina politics site FITS News and served as a spokesman for Mark Sanford during his governorship. “I said, mark my words, his Muslim wall is gonna be every bit as politically beneficial to him as his Mexican wall—and it has.”

in mid-december, less than a week after Trump proposed his ban and a little more than a month after he’d entertained the idea of creating a national database of all Muslims, the real estate tycoon received a conqueror’s welcome at a college gymnasium in Aiken, South Carolina. Outside the event, one of the best-selling souvenirs was a button quoting Trump’s campaign pledge to “bomb the shit out of ISIS.” A Trump supporter wearing a black St. Michael the Archangel t-shirt (“No evil shall befall thee,” it read) told me, “I think we’re at war with Islam.”

Inside, Mark Burns, an African American pastor who had recently endorsed Trump, began his invocation with a warning that “as of yesterday, they found over 200 AK-47s at a Muslim mosque in France.” (The British newspaper that reported this stated that those weapons were pulled from thousands of buildings over the course of three weeks, were not all AK-47s, and did not specify that any had come from mosques.) Then, midway through Trump’s speech, a Muslim man from Charlotte named Jibril Hough stood up in his seat and began to shout: “Islam is not the enemy.” The crowd responded—as it had been instructed by a Trump campaign staffer—by chanting Trump’s name until the Secret Service showed up to escort the man away. Hough’s glasses were knocked off his head in the tussle and a yellow badge, intended to evoke those that the Nazis forced Jews to wear during the Holocaust, fell off the front of his shirt. “It was like a star of David,” a nearby man in bib blue-jean overalls told me, sounding kind of confused, “but it had ‘Muslim’ on it.” (This has become a routine at Trump events—a month later, a woman in a hijab wearing an identical “Muslim” star of David was also kicked out of an event in South Carolina, despite protesting in silence.) Hough considered Trump’s presidential platform to be a particularly egregious moment in recent American politics. But, he stressed, when I caught up with him a few days later, Trump wasn’t saying anything new. The candidate was playing to fears that have flared up over and over again in South Carolina and elsewhere.

“The fever might break, but it’s like when you have a disease and you have it at bay—it’s not gone away,” Hough told me, referring to voters’ hostility toward his faith. “You [just] might have a period where you don’t have a rash. It’s like herpes or something.”

If you want to pinpoint the moment the anti-Islam fever first hit outbreak proportions, you’d start with the election of President Barack Obama. The idea that the Illinois senator was secretly a Muslim first took hold during the 2008 campaign and has refused to die in the years since—egged on by Trump, who floated the notion that the president’s birth certificate was being hidden from the public because it reveals that he’s Muslim. (The rumor is now almost canon; a recent survey by Public Policy Polling found that 66 percent of South Carolina Trump supporters and 60 percent of Cruz backers believe Obama is a Muslim.)

In South Carolina, Obama’s election was a catalyst for a grassroots conservative uprising. In 2009, ACT for America, a national organization founded two years earlier with the aim of combating the terrorism in the United States, began to take its message on tour. Almost a year to the day after Obama’s election, the group held a “Citizens in Action Training Conference” at a Marriott in downtown Columbia. Attendees learned that “political correctness” was aiding and abetting the rise of radical Islam, and they picked up tips on “how to detect telltale signs of possible terrorist behavior in your community.” As the tea party movement gained steam, South Carolina’s anti-Islam network grew with it. By 2010, ACT had a half-dozen chapters from Hilton Head to Greenville dedicated to combating the spread of Islam in their communities..

After the tea party landslide of 2010, South Carolina became one of the first states in the nation to consider a bill banning Shariah, the Islamic religious law, from being applied in state courts. According to Think Progress, the anti-Shariah bill was hatched by Chris Slick, a well-connected Greenville Republican then serving as ACT’s national online operations director. Slick—who currently directs the South Carolina efforts of John Kasich’s super-PAC—sent draft language for a bill to a friendly state senator. ACT then launched a public-relations blitz to get the bill through committee. It was ultimately tabled, but the legislature tried again in 2013—and again in 2014, and again in 2015. This January, it was passed by the state House of Representatives; it’s now awaiting judgment in the senate.

“We cannot have dual courts—a Shariah court and a US court,” Republican state Rep. Donna Hicks, a supporter of the measure, told me. “If you’re a Muslim living in America, [you] must submit to the US Constitution because that is the law of the land.” Hicks’ fear is that unless the legislature intervenes, Muslims will effectively be allowed to set up their own legal apparatus in the state—something that hasn’t happened yet and, under the Constitution, can’t happen, except in cases where both parties have agreed to clerical mediation (such as a divorce proceeding). When the bill was up for debate last year, though, she offered a more pointed warning: “If anybody looks at what happened at 9/11, it’s good to be proactive and not try to follow up and do something afterward.”

The anti-Shariah campaign’s most ardent champion in the state legislature might be state Sen. Lee Bright, who launched a primary challenge to Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham in 2014. In that race, Bright called Graham a “community organizer for the Muslim Brotherhood” and warned that terrorists were using student visas to infiltrate American communities. In June, he signed on as Cruz’s South Carolina campaign co-chair. Bright recently sponsored a bill to force the government to post the names, addresses, and telephone numbers of all refugees in a public directory, and to hold organizations that provide services to refugees responsible for any crimes they might commit.

ONE OF THE REASONS activists such as Michelle Wiles are so receptive to proposals by Trump and Cruz to block Muslim refugees is that they’re worried about the threat posed by Muslims who are already here. Wiles has even complained to her congressman about a specific group of American Muslims she believes have been plotting for years in her own backyard—the residents of a 44-acre compound near the North Carolina border known as Holy Islamville.

Behind the wild rumors that Islamville is a jihadi training camp are a few fragments of truth. In the early 1980s, a Pakistani sheikh named Mubarak Ali Shah Gilani began opening dozens of small compounds across the United States to create a home for the mostly African American adherents of his brand of Sufi Islam—including one, on 44 acres in York County, South Carolina. A 1997 Treasury Department report alleged that Gilani’s organization was responsible for “assassinations and firebombings across the United States” during the 1980s targeting “Muslims they regard as heretics and Hindus,” in addition to a number of white-collar crimes. And it was Gilani whom Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl had traveled to Islamabad to find when he was kidnapped and murdered in 2003, chasing a report that Gilani had sheltered “shoe-bomber” Richard Reid.

But the State Department stopped including Gilani and his network in its terror report in 2001 because of inactivity, and he was absolved of any connection to Pearl’s murder or to Reid. “American Muslims are better off in America than anywhere else and they will never do anything wrong against their country,” the cleric said in an interview with 60 Minutes during the Pearl investigation. A Syrian-American teenager from York County did try to join ISIS last year, but he had never been to Islamville. It is, by the county sheriff’s account, a close-knit community of gun-toting, God-fearing people, including a few veterans—a lot like the rest of South Carolina, in other words.

Yet suspicions about the compound have run wild. Activists began camping in the woods nearby and posting videos that purport to capture the sound of gunshots; helicopters have buzzed the property looking for evidence. A Virginia-based organization called the Christian Action Network eventually bought a billboard on I-26 east of Columbia in 2010 with the image of a scary-looking, dark-skinned man in a balaclava next to the words “Islam Rising…Be Warned.” The group’s president told the Charleston Post and Courier that it was focusing its advertising on South Carolina because of Islamville. Even Trump has fanned the flames of the conspiracy. In September, a New Hampshire voter asked him what he’d do to get rid of the terrorist training camps in the United States; Trump promised his administration was “going to look at that.”

After the Paris attack, South Carolinians’ concerns about their neighbors in York became so inflamed that Rep. Mick Mulvaney, a Republican whose district includes the community, decided to see the place for himself. He pronounced it harmless: “This is a group of law-abiding American citizens who are practicing their faith, and I saw no reason for anyone to see a threat.”

But by then, York County had moved on. Four days before Christmas, the county council passed a resolution opposing the settlement of refugees in the state. A councilman warned that residents could be murdered or “burned alive” if Muslim refugees came to South Carolina. Only one resident, a pastor, spoke in opposition.

YORK COUNTY IS ONE of six South Carolina counties to pass resolutions opposing the resettlement of refugees within their boundaries. These measures have no actual legal authority—even Wiles, who filed a cease-and-desist order to block the State Department’s resettlement program, accepts that it’s a losing argument in court. They are designed to send a message to the state and the feds that their communities are a kind of a no-go zone.

The arguments against taking in refugees aren’t just about ISIS. They also appeal to nativist populism. A billboard in Columbia, a short walk from the Capitol, features a Social Security card with the words “UN refugee” stamped on it. And when I met up with Wiles and Jim McMillan, the leaders of Secure Spartanburg County, they echoed complaints about government handouts that could just as well have been made in the 1970s. The way they see it, there’s no such thing as a good refugee—not even a Christian one. They’re all just coming here to take our stuff.

“They need to be fighting for their independence, instead of all those young bucks coming over here, and all those young bucks running away from that fight,” McMillan explained, referring to Syrian refugees. “When [Trump] talks about taking them out of our country, you don’t really have to take them out. All you really have to do is round up a few and let ’em know that that’s what’s going on, and that you’re cutting off this money trail, money supply, they’ll leave on their own…They’d be buying airplane tickets to get out of here when they know that they don’t get the free stuff any longer.”

“Somebody posted a picture the other day on Facebook, and they said, ‘This is a real refugee,'” Wiles added. “It was a picture of skin-and-bones people. Those people, that’s a true refugee. That’s people who need real help.”

“Especially the young men—they have cellphones, you see ’em texting,” McMillan said.

“Clothes, Aeropostale shirts,” Wiles interjected.

“Nice blue jeans—that’s right, Aeropostale shirts,” McMillan said. “They’re not true refugees.”

But the fears of refugees leeching off American taxpayers are a stand-in for what they’re ultimately afraid of—that Muslim refugees are secretly plotting to install their own form of government and turn the United States into one big Hamtramck. “We’re either gonna continue to exist as America, or we’re gonna be changed forever,” McMillan said.

SPARTANBURG, A MANUFACTURING CENTER in a deep-red patch of the state that helped send Rep. Trey Gowdy (of Benghazi committee fame) to the House, has emerged as one of the loudest centers of opposition to the resettlement of refugees by the Obama administration. Ann Corcoran, a Maryland-based writer and activist whose book, Refugee Resettlement and the Hijra to America, posits that jihadis posing as migrants are deliberately attempting to infiltrate the country, has called the city’s fight “Waterloo.” As she put it, “I think we will look back at this point in time with Spartanburg as the point where the history of refugee resettlement in America is changed forever.”

Residents first began protesting the arrival of refugees in the area last spring, shortly after Corcoran raised the issue at a national conference for Republican presidential candidates in South Carolina. From there, the complaints reached the desk of Gowdy, who griped to the State Department that he had been left in the dark over resettlement plans. Under pressure from legislators last spring, Republican Gov. Nikki Haley—who was once called a “raghead” by a state senator because her parents are Sikh—signed into law a proviso prohibiting the state from spending money on refugee resettlement in a county unless that county had authorized it to do so. (Hence the York County resolution and others like it.) The issue has not gone away; in August, the State Department felt compelled to dispatch Ann Richards, one of the agency’s top officials for refugee resettlement, to meet with activists in Spartanburg—including Wiles. Undeterred, Secure Spartanburg County hosted a Refugee Resettlement Summit for several hundred concerned residents in September and flew in a retired Immigration and Naturalization Service agent to talk about the holes in the refugee vetting system. A flier for the event quoted a Holocaust resister.

Rep. Donna Hicks, the Spartanburg lawmaker who previously backed the anti-Shariah bill, has found herself in the middle of the clash over whether to embrace or reject people in need—torn between friends (and many constituents) who support the refugees, and the vocal concerns of constituents who oppose resettlement. Her church provides financial support to World Relief, the nonprofit managing refugee resettlement in Spartanburg. World Relief’s Spartanburg director, Jason Lee, is a fellow parishioner. All told, World Relief Spartanburg has settled 69 refugees since it launched last spring—none of whom are from Syria. More than 80 percent of the newcomers are Christians, from places such as Ukraine and the Democratic Republic of Congo. (In order to keep out refugees who might come bearing the flag of ISIS, activists believe it’s essential to keep out all refugees.)

“We lose who we are as human beings and as an open nation that welcomes all people if we start seeing a devil behind every face,” Hicks told me.

Yet she also believes radical Islam poses a unique threat, and that the methods employed by ISIS challenge the efficacy of the refugee screening process. More to the point, so do the people who voted for her.

“I’m on Facebook a lot; every day I’m on there and so I’m watching what comes through,” Hicks said. “And there’s continually on my feed posts about refugees, Muslims, what ISIS is doing, Cruz said this, Rubio said this, Trump said [this]. People on Facebook, they’re just blowing up with that issue.” Three different constituents have given Hicks copies of Corcoran’s book.

In this climate, she has found that the kinds of issues that typically fire up her constituents have been cast aside. “As a matter of fact,” she said, “I had a press conference the other day—I prefiled a bill to defund Planned Parenthood in South Carolina.” No one showed. “[I] just couldn’t hardly even stir up media to be interested in that. But they were calling me at the same time, ‘Would you like to make a comment on the refugee issue?'”

WHAT MAKES TRUMP’S MESSAGE on Muslim migration so powerful in South Carolina and beyond is that it is a product not just of prejudice or ISIS-induced fear or 21st-century economic unease, but of all of these things. I was just leaving Spartanburg when I met a Trump supporter who drove this point home. I pulled over when I saw his sign on a small fishing boat, sandwiched between the outboard motor and a skeleton in a Santa Claus suit:

Fultons Tackle Box

It’s Safe

No Muslims Here

Fire Wood Gift Cards

Inside, amid the fishing supplies, I met Terry Fulton, a genial man with long white hair, a handgun on his hip and another in his waistband. He wore camo jacket over a Hell’s Angels shirt tucked into blue jeans. In his right hand, he held a cigarette.

“I think we gotta get rid of the Muslims,” he said, when I asked about the sign. “And then I think we gotta get rid of the Catholics.”

Wait, the Catholics?

“Well they started this shit during the Christian crusades! I’d be pissed too.”

Fulton guessed that he had met three or four Muslims in his life, and none of them had been very friendly. He claimed he would happily sell some bait to any Muslim who came in—though it’s hard to imagine that any would chance it. The point was “to let people know they don’t have to worry about a mass shooting over here at Fulton’s Tackle Box.”

Not surprisingly, he said he was backing Trump. “He’s like me—I don’t give a shit, I’m gonna tell you how I feel,” he said. But his reasoning ran deeper than personality. Fulton saw the refugee issue as one more area where hard-working Americans like himself were being pushed aside, their jobs and tax benefits offered up to someone new. “Alright, we got people living underneath frickin’ bridges, we got people on food stamps that don’t need to be, and everything else, and we’re gonna bring more people here that need help? I mean seriously look at the—we’re not living in the damn—this ain’t Disney World!”

As I made for the door, Fulton asked when I was flying home.

“Well, I hope there ain’t no Muslims on board,” he said, and then let out a cackling laugh. “I was just kidding you. I ain’t a racist, dude.”