It was around 10:30 p.m. when Steve Jacobs rolled down the gravel driveway. The air was warm for early January, even for Florida. Yellow boat lights bobbed on St. Augustine’s harbor, and the scent of star jasmine hung on the breeze. Jacobs stepped onto his porch and found the door still locked. It had only been a few days since he had come home to find it mysteriously ajar.

When Jacobs sat down to work, however, he noticed his crate of files was missing. He headed to the kitchen, opened the top of his coffee maker, and looked inside. The hard drive he’d stashed there was gone too.

A police officer soon arrived, checked the doors, dusted for fingerprints. He carefully wrapped the coffee maker in a plastic bag and said he would forward it to the FBI.

Jacobs had his suspicions as to why his house had been burgled. For more than a year, he’d been locked in a protracted legal battle with one of the wealthiest men on Earth.* Jacobs had filed a wrongful-termination case, accusing his former boss of ordering him to perform “illegal activities.” Could the burglary have been the desperate act of some yes-man or fixer, or even the gangsters he’d encountered while working in China? “I don’t know who is behind it,” Jacobs testified in a subsequent legal proceeding, admitting he had no facts to suggest it was his old employer. “I know who might have a benefit or interest in understanding what information I may have had.”

It’s a long way from a burglary in northeastern Florida to the battle for the White House, but there may be a connection: Jacobs’ tale and the documents his lawsuit has brought to light—some of which were on the hard drive in the coffee maker—provide a rare window into the business dealings of Sheldon Adelson, the casino magnate and political megadonor who could have a bigger role in selecting the 2016 GOP nominee than millions of Republican voters.

Over the past five years, I’ve sought to gain a fuller view of this complicated figure in American politics. I’ve written or co-written several major investigative pieces about Adelson, interviewing scores of casino executives and law enforcement officials and amassing thousands of pages of documents, including troves of Adelson’s legal transcripts and videotaped interviews. It has been a challenging process. Adelson has a track record of threatening to sue journalists. He sued one for describing him as “foul-mouthed.” He sued a columnist from the Las Vegas Review-Journal, driving him into bankruptcy over a few ill-chosen words. He once went after my reporting with a retraction demand but dropped it after my editors refused to make any changes to the story.

Adelson has used his fortune to reshape right-wing politics in both America and Israel, establishing himself as a GOP kingmaker in the post-Citizens United era. In December, he backed a secretive $140 million purchase of the Review-Journal, putting Nevada’s largest paper in the hands of its richest resident and a fixture of its biggest industry, and increasing his influence on Nevada’s early presidential caucuses. And now, as the 2016 campaign swings into high gear, Adelson faces a long-standing Justice Department probe that could generate embarrassing headlines for the mogul and the candidates he backs.

All this is why Jacobs’ case, due to go to trial in June, is so significant: The protracted litigation has illuminated just how Adelson built one of the world’s largest fortunes through his casinos in Macau—a Chinese territory rife with corruption where, Jacobs’ lawsuit alleges, Adelson not only tolerated, but sometimes even encouraged, illegal and unethical acts. In turn, Adelson has denied these accusations, describing Jacobs as a disgruntled ex-employee who was fired for insubordination and failure to properly address some of the issues raised in his own lawsuit.

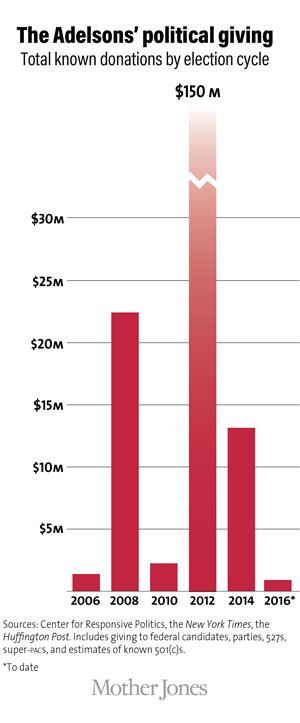

During the last presidential election, Adelson spent nearly $100 million directly (and reportedly another $50 million in undisclosed dark money) trying to thwart Barack Obama’s reelection. That included $20 million that he and his wife spent backing Newt Gingrich’s primary run and, after Gingrich dropped out of the race, another $30 million on a super-PAC supporting Mitt Romney. He gave another $23 million to American Crossroads, the super-PAC once led by Karl Rove. His dark- money contributions reportedly buoyed conservative organizations such as the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity.

And Adelson has an arguably greater political influence in Israel, where he founded the free daily Israel Hayom, reportedly spending tens of millions of dollars to bankroll it. Now the country’s most widely read publication, Hayom serves as the house organ for Prime Minister Benjamin “Bibi” Netanyahu, who rode to reelection last year after stoking fears that “Arab voters are heading to the polls in droves.” This year’s Republican candidates, many of whom have made the pilgrimage to Las Vegas in what has become known as the “Adelson primary,” know that the mogul’s patronage depends on their positions and tone toward Israel.

A diminutive 82-year-old with a lumpy face and a puff of thinning red hair, Adelson is the 13th-richest man in the United States, worth more than $20 billion, according to Forbes. Though he made his initial fortune in Vegas, he joined the ranks of the superrich following his 2001 investment in Macau, a once run-down seaport an hour’s ferry ride from Hong Kong that in the last decade has overshadowed Vegas to become the world’s gambling capital. Adelson’s casinos in Macau, a special administrative region of China, provide the majority of the revenue for his company, Las Vegas Sands. But beneath Macau’s glitz lurk organized crime, corruption, and a shadow banking system that has allegedly laundered billions of dollars for China’s ruling elite. In 2013, the chair of Nevada’s powerful Gaming Control Board told a federal commission that it was “common knowledge” that the lucrative VIP rooms in Macau casinos have “long been dominated by Asian organized crime.” That same year, a federal commission cited a study finding that more than $200 billion in “ill-gotten funds are channeled through Macau each year.”

Which raises the question: Is dirty money spent by corrupt Chinese officials at Macau casinos flowing into our elections, at least indirectly? “With Citizens United, there’s an awful lot of money sloshing around in our political process,” said Carolyn Bartholomew, vice chairman of the bipartisan US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, a congressional advisory body that produced a scathing report detailing Macau’s vulnerability to money laundering by such officials. “People have a right to know whose money that is, and that the proceeds being spent in the political process are not from illegal and illicit activities.”

The key to finding out may be Steve Jacobs’ lawsuit. “This case will never be settled,” Adelson has vowed, and he’s kept his word through more than five years of bruising and reputation-staining proceedings. As the billionaire promised reporters in Macau, “When we win the case, we will go after him in a way that he won’t forget.”

Adelson has always been a fighter. The son of a Jewish Lithuanian cab driver and a British-born mother who ran a small knitting service, Adelson grew up in the Dorchester neighborhood of South Boston. As an infant, he slept in a dresser drawer, until he joined his sister and two brothers on the floor. “I didn’t know we were poor, but we were very poor,” he would later say in testimony. “Church mice were rather affluent compared to our family.”

Dorchester was home to a thriving Jewish community, but also to Irish toughs who Adelson has said forced Jewish kids to travel in packs to avoid being attacked with brass knuckles, rubber hoses, and chains. “I just have a lot of memories of being beaten up for being Jewish,” he said in a deposition. “And when you have been beaten many, many times over a period of years, you get to know what a feeling of hostility and hatred is.”

Adelson clawed his way to a better life through thrift, opportunism, and hard work, emerging, by many accounts, as a prickly, combative scrapper. At age 12 he starting selling newspapers on the street, and soon he moved on to buying control of street corners. His first corner faced the employee entrance to Filene’s Basement, a thriving department store in downtown Boston. Borrowing $200 from his uncle, the treasurer of a credit union, he soon bought another corner. At age 16, he invested in 125 candy machines that he set up in shoe factories and later at all-night gas stations, where cab drivers like his father would fill up their cars, thereby earning Adelson profits around the clock. He thrived, despite the looming presence of the Patriarca gang of Boston, which was involved in the vending-machine business at the time.

Adelson graduated from high school, joined the Army, and upon discharge returned to serial entrepreneurship. “I thought I couldn’t hold down a job because I went from thing to thing,” he would later say. “I’ve done over 50 different things in my life.”

Adelson became a venture capitalist in the 1960s, investing in a bull market and losing a fortune when it went bust. He sold condominiums. He started a charter travel service. But he hit upon his first great success in 1979 when he created Comdex, a computer trade show that eventually drew more than 225,000 people to Las Vegas, an event so large it had to be held in multiple locations. Adelson decided to build his own convention center, and he found some land owned by the Sands Hotel, which he purchased in 1989.

As the hotel’s new owner, Adelson had to seek a gambling license and endure a rigorous background check. The Nevada Gaming Control Board dug up scores of lawsuits in which he had failed to pay his debts. Massachusetts had suspended his real estate license. His longtime friend and business partner Irwin Chafetz (who still sits on the board of Las Vegas Sands Corp.) had ties to a man named Henry Vara who’d been accused of skimming from the gay bars he owned, one of which was notorious for prostitution.

The regulators asked tough questions about Chafetz’s associations, but Adelson told them that he didn’t want to drop his friend from the application. “That man and I are almost like Siamese twins,” Adelson told the board. “We are almost joined physically. There is nothing in the world that can convince me he would do anything wrong.”

Adelson would win his license, but not before one of the board’s regulators warned him of the dangers of this kind of loyalty. “I may have some problems,” the official said, “with your ability to judge people and character.”

Two years after the purchase of the Sands Hotel made him a casino magnate, Adelson married his second wife, Miriam Ochshorn, an Israeli doctor who would nurture his passion for her home country. Over time she came to assume a substantial role in their family’s business and political interests, and she has been spoken of as a potential successor to her husband.

In 1995, Adelson sold his trade show for $862 million and hired a superteam of casino industry veterans to grow Sands Corp. One of them, William Weidner, became the company’s president the following year. Handsome and hard-nosed, Weidner would help run the company for 13 years as it expanded, first in Vegas and eventually across the Pacific.

The old Sands Hotel had once played host to Frank Sinatra and his legendary entourage. Adelson demolished it. (“It was the home of what they called the Rat Pack, a very glamorous history in Las Vegas,” Adelson later said. “So I tore it down.”) In its place, he built the Venetian, inspired by the city where he and Miriam had honeymooned. When it opened in 1999, the faux-Italian complex was the largest gambling resort Vegas had ever seen, and competitors derided him for building too many rooms. But it was soon packed.

A year later, Adelson flew to Hong Kong at the urging of his younger brother Lenny to meet Richard Suen, a well-connected entrepreneur who told him that China was preparing to allow international investment in Macau. “We think one day…it’ll be opened up and other people will be able to come,” Suen said, according to a deposition Adelson later gave. “I’m typically not interested in investing where the American or Israeli flags don’t fly over schools,” Adelson replied. But Weidner, according to depositions, encouraged him to explore the relationship.

Suen introduced Adelson and Weidner to the vice premier of China in early July 2001. They met in the Purple Light Pavilion of Zhongnanhai, the Chinese equivalent of the White House, near Beijing’s Forbidden City. After 45 minutes together, the vice premier invited Adelson to submit a bid for a gaming license in Macau.

That same weekend, Adelson also met with the mayor of Beijing, who asked him for some help: Congress was considering a resolution to protest China’s bid to host the 2008 Olympics, based on the country’s human rights violations. “We’re standing in a parking lot of the Beijing convention center. Sheldon picks up his cellphone and calls Tom DeLay in Houston,” Weidner later said in a deposition. Adelson reached the House majority whip at a Fourth of July cookout. “You can hear him—Tom DeLay talks very loudly over the phone. Tom says, ‘I’m chewing on my fourth piece of rubber chicken.'”

DeLay was a co-sponsor of the resolution, which had overwhelming bipartisan support and was particularly popular among evangelicals concerned about Chinese persecution of Christians. But Adelson had taken DeLay to Israel and lavishly supported Republican campaigns. DeLay said he would see what he could do. “Three hours later,” Weidner said, “DeLay calls and tells Sheldon, ‘You’re in luck. I’d like to get that bill, but I can’t do it—we’re not going to be able to move the bill.’ Sheldon goes to the mayor and says, ‘The bill will never see the light of day, Mr. Mayor. Don’t worry about it.'”

DeLay later said he couldn’t recall the conversation, and Adelson denied trying to block the bill. But, according to Weidner, the call made an impression on the Chinese. Stanley Ho, the debonair tango enthusiast who was the godfather of Macau’s gaming operations, later pulled a Sands executive aside at a party in Hong Kong with good news about the company’s license application, telling him, “By the way, that Olympic thing: I think you guys won the bid,” Weidner later recalled in a deposition. “That’s what I hear back from my guys in Beijing. Congratulations.”

At the time, Ho held a virtual monopoly on gaming in Macau, long a hotbed for piracy, gold smuggling, and espionage. According to US regulators, Chinese criminal organizations called triads had penetrated his casinos, even operating out of their private VIP rooms. In 1999, just before China assumed control of the territory from Portugal, a triad war erupted as gangs fought for dominance. Criminals shot each other in broad daylight; car bombs scattered limbs across the ancient stone sidewalks. Weidner wondered how American casino operators would “ever open in that kind of lawless environment.” Violence wasn’t the only obstacle: Nevada had spent decades purging itself of mobsters like Sam Giancana and Meyer Lansky, and the state had strict rules that could jeopardize Sands’ gambling license if the company associated with organized crime anywhere in the world.

China prohibits its citizens from bringing more than $3,000 across the border into Macau, a fraction of what a high roller can spend on a hand, let alone in an evening. This restriction led to the emergence of junket companies, which ferried wealthy gamblers to Macau and extended them credit to get around the currency constraints. The junket business provided a legal construct to bring in vast sums from China. This made Macau a popular destination for corrupt Chinese officials: They could turn their ill-gotten gains into chips, collect the winnings, and deposit them in offshore accounts.

The junkets were critical to the success of the casinos, which relied on big-spending whales for a huge portion of their business. Gambling debts are not collectible in Chinese courts, so junket companies or their triad affiliates did the job—sometimes brutally, according to a report by the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission. Chinese newspapers are filled with grisly tales of gamblers who failed to repay their loans and ended up kidnapped, imprisoned in cages, threatened with dismemberment, injected with drugs, or forced to take revealing photos. Triad members might give an indebted gambler “a list of options,” according to Nelson Rose, an expert in Macau and gaming law at Whittier Law School: “‘We will rape your wife and put her in a brothel. We will hang you by your feet off one of the tallest buildings.’ They do find bodies in mainland China linked to gambling debts in Macau.”

In May 2004, thousands of people spurred by rumors of free chips swarmed outside the Sands Macau for its grand opening. The crowd literally tore the main doors from their hinges and smashed in 16 other entrances. Escalators groaned under the weight of gamblers rushing to the tables.

A similar frenzy gripped the New York Stock Exchange later that year, when Las Vegas Sands Corp. (LVSC) went public and Macau-mad investors pushed the new stock up by 61 percent in a single day. Almost overnight, Adelson was propelled into the ranks of the world’s superrich, his worth rising from $1.8 billion in 2004 to more than $11.5 billion in 2005. “He got rich faster than anyone else in history,” Peter W. Bernstein and Annalyn Swan wrote in All the Money in the World, their book on the Forbes 400. For years after the company went public, Adelson’s personal shares earned him about $1 million every hour.

The Sands Macau made back its $256 million in construction costs in 10 months, and it initially avoided entanglement with the junkets. But, according to a deposition Weidner later gave, that soon changed. Over the next several years, as I reported in articles for Reuters and ProPublica that were produced with the University of California-Berkeley’s Investigative Reporting Program, the casino partnered with two junkets connected to an organized-crime figure in Hong Kong who has been under the scrutiny of US law enforcement at least as far back as 1992, according to court records, financial filings, and the casino’s own internal reports. By 2007, junkets were providing more than two-thirds of the revenues at Sands’ Macau casinos, according to the company’s Securities and Exchange Commission filings.

That year, Adelson opened his second outpost in the Chinese enclave: the Venetian Macau, which remains the largest casino in the world. The stock price of LVSC hit an all-time high that October, lifting Adelson’s worth to $26.5 billion. And his newfound wealth turbocharged his political giving.

Adelson had been a political donor for decades and was even named a Bush Pioneer for raising more than $100,000 for George W. Bush’s 2004 reelection campaign. But that was peanuts compared with what he would stake now. He bankrolled nearly the entire $30 million budget of Freedom’s Watch, which he had launched as a right-wing counterpoint to MoveOn.org, and used it to drum up support for Bush’s 2007 surge in Iraq. Weidner sat on the board of the group; Karl Rove was a key adviser. When the 2008 campaign drew near, Adelson crowed to the Wall Street Journal that the cavalry was “coming over the hill, bugles blaring. I’m looking for a horse…and trying on chaps and boots and stirrups.” But Freedom’s Watch soon dissolved after staffers bridled at Adelson’s micromanagement.

Meanwhile, trouble was brewing in China. Richard Suen, the fixer who helped introduce Adelson to Chinese officials, had sued over a deal he had hammered out with Weidner: For helping the company get a gambling license, Suen said, he’d been promised $5 million and 2 percent of LVSC’s Macau profits. But when the case went to trial in 2008, Adelson claimed he refused to pay Suen because Suen had fallen short of a promise to “deliver a license,” since the company’s entrée to Macau had still been subject to a competitive bidding process. When Adelson took the stand, he accused Weidner of agreeing to inappropriate terms with Suen—terms Adelson claimed to have not properly understood because he had been too sedated on painkillers. (Adelson suffers from peripheral neuropathy, a painful condition that has left him largely wheelchair bound since 2001.) A jury didn’t buy it and awarded Suen $43 million. Adelson appealed, but in 2013 a new jury awarded Suen $70 million. Adelson has appealed again, to the Nevada Supreme Court. The case is pending.

But the real damage, according to Weidner, came after officials in Beijing learned their dirty laundry was being aired at trial. Adelson’s conversation with DeLay came to light, as did connections between Suen’s firm and China’s top officials. The fatal blow was a photograph, displayed in the Las Vegas courtroom, of Adelson, Suen, and Weidner smiling alongside the vice premier of China. “Sheldon really fucked the pooch on that one,” Weidner later told me.

Within a month of the 2008 trial’s close, Beijing moved to shut down a huge goodwill project Sands had undertaken—the Adelson Center for US-China Enterprise. Sands had already spent more than $50 million on the center, which was intended to connect US companies with Chinese partners, but “the government didn’t want anything to do with a building that had Adelson’s name on it,” Weidner told me.

China imposed severe restrictions on travel visas to Macau that year, causing visits from the mainland to drop by nearly 20 percent. A State Department cable, made public by WikiLeaks, said the squeeze was a result of China’s growing concern over the junket trade. “The fact that mainland gamblers account for the majority of funds flowing into Macau appears increasingly undesirable to Beijing,” the cable read. “The perception is widespread that, with the implicit assistance of the big ‘junket’ operators, some of these mainlanders are betting with embezzled state money or proceeds from official corruption, and substantial portions of these funds are flowing on to organized crime groups.”

All this compounded the damage inflicted by the unfolding global economic crisis. Bank credit froze just as Sands was building massive new casino projects in Macau. LVSC had more than $10 billion in debt and was on the verge of bankruptcy when Adelson injected $1 billion of his own money to keep it afloat. But that was not enough to hold onto Weidner, who resigned in March 2009, describing his management conflicts with Adelson as a “junkyard dog fight.”

After Weidner left, Steve Jacobs was brought on to address the problems in Macau. Though Jacobs had no experience in the gambling sector, he was a turnaround artist who’d overseen the corporate restructuring of Holiday Inn and a luxury hotel chain in Europe. “I typically take on assignments that others can’t or won’t,” Jacobs later boasted.

Jacobs recalled being shocked by his first visit to the Venetian Macau. While Adelson has testified that Sands had “zero tolerance” for prostitution, Jacobs says he “walked on the floor and saw rampant prostitution. It was blatantly, blatantly obvious.” Although it was legal in Macau, Jacobs felt that it was bad for business.

An average of 40 to 60 prostitutes walked the Venetian’s floors on weekends, outnumbering security personnel, according to company documents entered as exhibits in the Jacobs case. The internal security reports say the women were “frequently under 18 years” old and trafficked from China’s inner provinces by “vice syndicates” to work out of rooms the prostitutes appeared to have received free of charge.

Jacobs proposed ridding the casino of prostitution. But he was soon informed, he later recalled, that management had decided “to allow prostitution as it would help our overall gaming revenue.”

According to Jacobs, Sands’ new president, Michael Leven, told him not to “make it a big deal…The board knows prostitution is going on.”

“Does Sheldon know prostitution is going on?” Jacobs remembers asking.

Leven, he testified, said, “Yes, but it’s legal. It’s what the gamblers want.”

To shore up LVSC’s dismal finances, Jacobs began preparing to spin off the company’s Macau holdings into Sands China, a new entity that could be independently listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange. It was a difficult task in the rocky economic climate, and Adelson’s combative style made the job no easier. Jacobs would later claim in litigation that he spent much of his time repairing “strained relationships with local and national government officials in Macau who would no longer meet with Adelson due to his obstreperous behavior.” Animosity over Suen’s lawsuit also lingered “like a festering sore,” according to an internal memo by an LVSC board member. “The central government attitude about [Las Vegas Sands] has changed.”

Macau’s Beijing-selected chief executive, Edmund Ho (no relation to Stanley), privately suggested to the board member that Adelson “should sit back a bit, enjoy his family and his time and let his executives handle the operations in Asia,” according to the memo. As Jacobs was laying the groundwork for the Hong Kong public offering, he approached Ho about getting an exemption from local real estate laws for a condominium project. Ho refused to grant it.

According to Jacobs, Adelson “became enraged and stated that Ho had ‘promised’ him” the exception. Two years earlier, Adelson had paid a substantial settlement to a group of businessmen who, like Richard Suen, were seeking payment for helping to facilitate Sands’ entrée into Macau. The litigants had been particularly close associates of Ho, and Adelson wanted Jacobs to remind the executive of how he’d dispensed with the case: According to Jacobs’ lawsuit, Adelson instructed him to “inform the ‘son of a bitch’ that Adelson had settled a lawsuit for $40 million dollars to keep Chief Executive Ho out of jail.” Instead, Jacobs reported the conversation to the company’s chief counsel, according to court filings.

Undeterred, Adelson continued to push the Macau government on the condo permit. He hired Leonel Alves, a top Macau politician, as the company’s local counsel. In late 2009, Alves emailed Jacobs to report he had been approached by a “high-ranking official in Beijing” who suggested a way to get approval—but it would be “expensive,” more than “300m” US dollars, Alves later wrote, “to be deposited in a mutually accepted escrow account.” Jacobs refused, believing Alves was suggesting a “payment for Chinese officials,” according to court documents. When Alves submitted invoices for his work, they were significantly higher than what the company had expected, triggering concerns that such payments could present a risk under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which prohibits US companies from bribing public officials overseas.

When Sands China, the spinoff, went public in November, it raised more than $2.5 billion, and Jacobs, now president of the new entity, was heralded as LVSC’s savior. “There is no question of Steve’s performance,” Leven wrote in an email to a board member. “The Titanic hit the iceberg, he arrived and saved the ship.” Rob Goldstein, the current president of LVSC, later said in court that he believed Jacobs was Adelson’s heir apparent.

But Adelson was now challenging Jacobs on the smallest of details: The casino didn’t have enough slot machines. There weren’t enough seats at the noodle bar. Even Miriam chimed in, relaying a complaint via a secretary: “The person speaking over the loudspeaker on the ferry…should speak with much better English—not with such a heavy accent.”

Meanwhile, Alves continued to press Adelson for his fees. Though Jacobs had initially refused to release the money, Adelson assured the Macau politician that he would make sure Jacobs would “resolve any issues immediately.” Despite Jacobs’ legal concerns, Adelson instructed him to pay Alves, according to internal emails, “regardless of cost.” In subsequent legal proceedings, Adelson has defended the payments.

Soon afterward, Reuters published my investigation showing that Sands had partnered with two junkets underwritten by the alleged triad boss Cheung Chi Tai to bring gamblers to its tables. According to testimony in a Hong Kong trial, Cheung was the “person in charge” of a Sands VIP room and, company documents show, entitled to a share of its profits. Witnesses in the trial said he ordered the killing of a junket worker suspected of cheating. The man was not killed, and Cheung was never charged in connection with the plot, but the trial and article linking Cheung to the junket was “enough to cause major headaches” for Sands and put the company’s invaluable Nevada license at risk, according to Whittier Law School’s Nelson Rose.

“When the article came out, Mr. Adelson was quite animated,” Jacobs later said in a deposition. The company demanded that Reuters retract the story, denying the casino had anything to do with the alleged gang leader. In fact, Cheung-affiliated junkets reaped as much as $160 million in commissions from Sands casinos in 2009, an internal email shows. If the payments were made according to Macau’s traditional arrangement, it would suggest that the two junkets brought Sands some $400 million in business—nearly as much as the conglomerate’s Las Vegas revenues that year.

Sands’ chief counsel abruptly gave notice just days after the article appeared. In the weeks to follow, he complained that the company’s protest of my story contained inaccuracies. Reuters published no correction or retraction.

But that article prompted Sands to embark upon its own internal investigation, which uncovered documents showing the casino had extended more than $32 million in credit to junkets backed by Cheung, according to the company’s court filings. Jacobs wanted to tell LVSC’s board about the relationship, but he says Adelson stopped him. According to Jacobs’ lawsuit, when he speculated about the risk the alleged Cheung connection presented to Sands’ Nevada license, “Adelson scoffed at the suggestion, informing Jacobs that he…controlled the regulators, not the other way around.”

On the morning of July 23, 2010, barely eight months after the company’s successful Hong Kong public offering, Jacobs was called to a meeting with Leven in Macau, ostensibly to discuss the upcoming board meeting. Instead, he said in a later deposition, “two security guards walk in. They say, ‘You’ve got to leave.’…I get some clothes…They take me directly to the ferry.”

Jacobs sued for wrongful termination in October 2010. “We’re not saying the Steve Jacobs lawsuit is going to bring the [Sands] party to a halt,” a Macau-based financial intelligence company wrote in a newsletter at the time. “But we do think…he has several characteristics that make us believe he is a far more formidable opponent than any former employees Adelson has tried to face down before. These include supreme self-confidence, the courage of a lion, and the cunning of a trained lawyer. And dirt. Lots and lots and lots of it.”

Las Vegas Sands Corp. disclosed in March 2011 that the Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission had launched bribery investigations based on Jacobs’ allegations. The wide-ranging inquiry delved into the Alves relationship and the aborted Adelson Center for US-China Enterprise in Beijing, according to sources familiar with the investigations. An internal Sands audit, according to the Wall Street Journal, revealed more than $50 million in payments made through Yang Saixin, a businessman who was the Chinese point man on the Adelson Center project. The ongoing federal investigation is said to be looking into whether any of the money paid to Yang was transferred to Chinese public officials in violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

While Yang has denied any wrongdoing, an internal Sands memo describes him as highly influential; his parents “knew [President] Xi Jinping’s parents, implying a strong connection to Zhongnanhai (the White House of China).” Adelson, the memo added, twice met personally with Yang. Yet Adelson later denied any knowledge of the center that would have borne his name, placing the blame squarely on Sands’ former president. “Bill Weidner came to me and said that he wanted me to ask President Bush to come and cut the ribbon for the Adelson Center, and I said, ‘What’s the Adelson Center?'” Adelson recalled in a 2012 deposition. “That’s the first I heard of it.”

Even as Adelson was contending with a federal investigation, he was bankrolling the campaign of Mitt Romney, whom he called the “president-elect.” In a September 2012 interview with Politico, Adelson complained that he had been targeted by the Obama administration for his political activity. He said he feared Obama’s reelection would bring “vilification of people that were against” the president. Adelson claimed that the Obama administration’s prosecutors had leaked information about the Justice Department inquiry to suggest to fellow Republicans that “‘this guy is toxic. Don’t do business with him. Don’t take his money.'”

In 2013, LVSC acknowledged in its public filings that it had “likely” violated the accounting provisions of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Adelson has admitted sitting for interviews with investigators from the Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission. According to a Justice Department source, the investigation may conclude this year—which could put the outcome squarely in the middle of the presidential campaign.

In late April 2015, I watched Adelson roll his royal purple motorized wheelchair out of the elevator and onto the 14th floor of the Clark County Regional Justice Center in Las Vegas for a hearing in the Jacobs lawsuit. A bright morning sun lit the hallway as the casino magnate, surrounded by his lawyers, a bodyguard, and his wife, Miriam, made their way to the courtroom. When Adelson’s party crossed paths with Jacobs and his attorneys, the two combatants briefly locked eyes.

Adelson was in pinstripes, his leather shoes worn but polished. A gold handle capped his cane. His demeanor was calm and gentle as he chatted with his entourage about the 1966 movie Cast a Giant Shadow, about the creation of Israel. “Sal Mineo was in that,” Adelson offered cheerfully. His companions murmured but didn’t reply, perhaps because Mineo wasn’t in the film.

On the stand, Adelson pushed away a jar of M&M’s. “I can resist everything but temptation,” he told Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez. He appeared unruffled as Jacobs’ attorney repeatedly presented him with memos, emails, and contracts. “I don’t get involved in the day-to-day activities,” he said dismissively. “My age is advancing.”

But when the questions turned to Jacobs, his tone darkened. He made clear that he had wanted to fire the “incompetent” executive within months of hiring him. Jacobs, he said, had tried to run the show without him: “He tried to go behind my back to different board members to get things done, so he wouldn’t have to report to me.” And, he said, his voice rising, “He squealed—like a pig squeals—to the SEC and to the DOJ!”

Even though Rob Goldstein, Sands’ current president, admitted in testimony to having done business with Cheung Chi Tai, Adelson denied his company had any “direct connection” with the alleged gangster. At the same time, he insisted he had been right to fire Jacobs for trying to cut ties with the junkets. “He wanted to throw out 50 percent, 60 or 70 percent of the gross gaming income,” Adelson told the courtroom. “This was insanity. He purposely tried to kill the company.”

But while Adelson was defending the junkets’ importance in court, China was shutting them down. As part of a wide-ranging anti-corruption campaign, authorities raided Cheung’s Hong Kong apartment in March 2014 and later charged him with laundering $232 million. Since then, the junket industry has withered and LVSC has lost more than 58 percent of its value. Adelson, in turn, has lost some $16 billion, more than a third of his net worth.

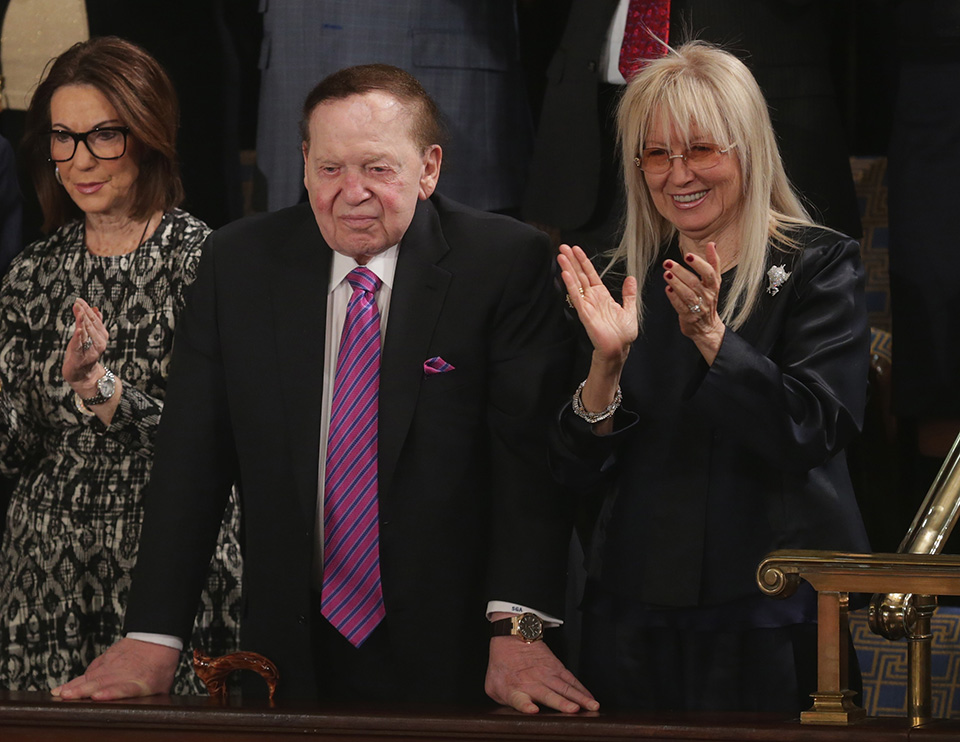

Adelson’s wealth may have shrunk, but he’s still a high roller in politics, as was evident when he came to Washington last March to watch Netanyahu give a speech before Congress.

Sheldon Adelson, left, and his wife, Miriam, right, attend Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s March 2015 speech before a joint session of Congress. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

In the days leading up to the event, Marco Rubio, said to be favored by Adelson in the 2016 election, dined with the casino magnate in a private room of the Charlie Palmer steak house, near the Capitol. The morning of the speech, Adelson, clad in a dark suit and an eye-catching fuchsia tie, claimed a prime seat. Nearby was Newt Gingrich, who, within weeks of receiving his first donation from Adelson in 2012, had declared Palestinians “an invented people.” James Hagee, the evangelist who created Christians United for Israel, came as a personal guest of Adelson. And there was Rabbi Shmuley Boteach of New Jersey, whom Adelson once supported in an unsuccessful bid for Congress. Days earlier, Boteach’s organization had run a full-page advertisement in the New York Times showing National Security Adviser Susan Rice flanked by photoshopped skulls, attacking her criticism of Netanyahu’s appearance as tantamount to supporting a “genocide” of the “Jewish people.” The ad promoted a Capitol Hill panel on Iran featuring Ted Cruz, said to be Miriam Adelson’s choice for president.

The other presidential hopefuls, too, have made sure to be on Sheldon Adelson’s radar, most notably in December, when they all appeared onstage at his Venetian resort for a prime-time debate. Last spring, Adelson sent word that if one of Jeb Bush’s campaign advisers went through with plans to address a dovish Israel policy organization, it would cost Bush “a lot of money.” Even Donald Trump, who swore off contributions from his fellow billionaires, sent Adelson a glossy booklet of photographs from a gala where he accepted an award for boosting US-Israel relations. “Sheldon,” the candidate scrawled across the cover, “no one will be a bigger friend to Israel than me!” (Adelson has promised to support whoever wins the nomination.)

The billionaire’s expanding power was underscored the morning after the debate, when the Review-Journal revealed that Adelson and his family were behind a shadowy holding company that had purchased the newspaper weeks earlier and kicked off a media frenzy. Adelson has promised not to meddle with editorial decisions at the Review-Journal, which by virtue of its location frequently covers his company, his industry, and his favorite politicians. But even if he honors that pledge, staffers have speculated that it doesn’t matter: There are any number of subordinates who will aim to please the boss.

As the sale was being finalized, publishing executives ordered a team of three reporters, over newsroom objections, to undertake a detailed investigation into the courtroom habits of three Las Vegas judges. One of the targets was Elizabeth Gonzalez, whom Adelson, just days before, had failed to get removed from the Jacobs case. In the run-up to the trial, Gonzalez had clashed with Adelson on the stand, ruled against the company’s attempts to move proceedings to Macau, and fined its lawyers for deception and withholding documents. “When the request was handed down, it seemed like little more than a waste of time and resources,” Michael Hengel, then the paper’s editor, recalled. “Now I wonder what really was behind it.”

The Review-Journal never published anything related to the investigation, but a mysterious article, highly critical of Gonzalez, appeared under a pseudonym in a Connecticut newspaper—owned by Adelson’s frontman in the Las Vegas acquisition.

That paper’s owner later took responsibility for the story and issued a mea culpa, but the episode spoke to the growing influence of a man who didn’t become one of the world’s wealthiest people for nothing. “I live on Vince Lombardi’s belief: ‘Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing,'” Adelson once said. “So I do whatever it takes, as long as it’s moral, ethical, principled, legal.”

Correction: The article initially misstated when Jacobs launched his case.