Nick Ut/Associated Press

The Trump administration recently announced a rule that will gut the Obamacare mandate that required most employers cover the cost of birth control in their insurance plans. The rule, which will make it much easier for employers to opt out of covering contraceptives, is just one of a handful of recent changes Trump has made that threatens Obamacare. But there’s a problem with Trump’s plan to make it harder for women to get birth control: Many states saw it coming.

The contraception mandate, enacted in 2010 as part of the Affordable Care Act, was the first federal guarantee of contraceptive coverage for the millions of women who get insurance through their employers. The mandate also included a requirement that insurers cover FDA-approved contraceptives without cost-sharing, meaning women get it for free. At the time, the changes were lauded by reproductive rights advocates as “the greatest step forward for women’s reproductive health in decades.” Even when the Supreme Court ruled in 2014 that a narrow set of employers with religious objections could opt-out of contraception coverage, birth control access was still essentially guaranteed, because an employer filing for an exception triggered separate contraception coverage for its affected employees.

Then Trump was elected and with him came vast promises to undo Obamacare and protect religious freedom. His new birth control rule, which took effect immediately when it was issued on Oct. 6, tackles both: It allows virtually any employer to opt out of birth control coverage if they feel it violates their religious or moral convictions, and those employers don’t have to notify the government to prompt separate contraception coverage. Moreover, it allows insurers themselves to opt out of coverage.

This has the potential to leave millions of women without birth control and facing the daunting task of navigating the tangle of contraception coverage laws in their individual states. In some cases, that could be disastrous. But, in many places, states have already taken steps that could counteract the Trump effect.

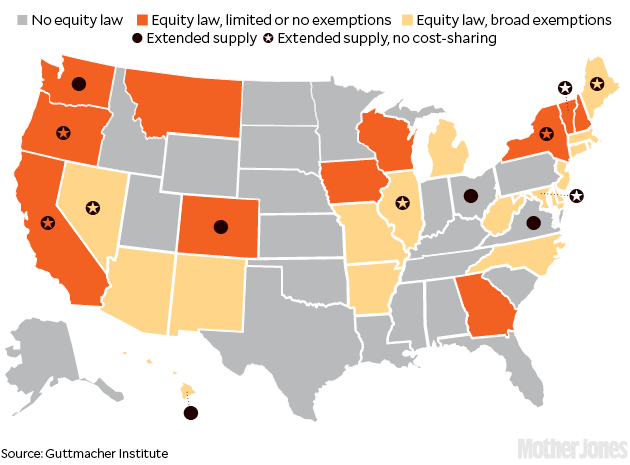

Before Obamacare, birth control coverage varied widely by state. Starting in the 1990s, when women’s health advocates were enraged by reports that Viagra but not birth control was covered, some states started passing “contraceptive equity” laws—most basically, measures that protect access to prescription contraception, like the Pill, by requiring that insurers include some coverage of it. Even a traditionally red state like Arizona, for example, has had a law on the books since 2002 that requires most insurers cover contraceptives, albeit with religious exemptions and with cost-sharing.

By the time Obamacare passed in 2010, 28 states already had some form of “contraceptive equity” instructing most insurers to at least cover prescription contraception. In the handful of years after the passage of Obamacare, which in most cases did more than the state law to ensure affordable contraception access, a handful of states updated their contraceptive equity laws to bring them more in line with federal rules. California, for instance, passed a measure enshrining most of the federal contraception mandate on the books in the state in 2014.

Since the 2016 campaign started making the demise of Obamacare seem like a true possibility, there’s been yet another surge of contraceptive equity laws in states across the political spectrum. In Vermont, for instance, a 2016 equity law removed financial hurdles to getting long acting, reversible contraception like IUDs. Equity laws got an even further additional boost after Trump won the election, when six more states—Colorado, Maine, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and Virginia—updated their laws to bring them more in line with the Obamacare rules. They likely did so “because they’ve been afraid of what the federal government might do,” says Elizabeth Nash, state policy expert at the nonprofit Guttmacher Institute, which studies reproductive rights issues. And some of those new laws, says Nash, set in place protections that even Obamacare did not include—for example, including coverage of over-the-counter contraception methods, like the morning-after pill, as well.

Consider the example of Nevada. In June, a month after a draft of the Trump contraception rule first leaked to the press, the state’s Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval signed a measure requiring, among other things, that insurers cover 12 months of birth control at a time, with no co-payments. “The thought of losing the federal protections was in the back of our minds,” Nevada delegate Ariana B. Kelly, the bill’s sponsor, told the New York Times. Days later, Colorado passed a nearly identical bill.

In all, there are currently 28 states with some sort of contraceptive equity law in effect. Some exceed the Obamacare standards while others still fall short, according to data provided by Guttmacher.

Women in these states are far less vulnerable than those in states without any contraceptive equity laws, but it’s important to note that they can still be impacted by Trump’s new rule. Many states’ contraceptive equity laws include broad exemptions for insurers and employers, making it easy for them to opt-out of coverage for religious reasons, or otherwise. For example, Illinois, which passed a contraceptive equity law mid-2016, requires coverage of most over-the-counter methods and prohibits cost sharing, but it also allows religious employers to opt-out of coverage. Maryland’s law, which doesn’t take effect until 2018, includes expansive exemptions for religious groups. In contrast, California and Oregon, whose laws were passed in 2014 and 2017, respectively, only allow churches and church associations to opt out. And eight states, ranging from Washington to Georgia, don’t include any religious exemptions, making them the places where contraception coverage is most protected.

With state legislatures currently out of session, it’s hard to predict whether Trump’s new rule will inspire more states to fill the gap left by the change. Some reproductive rights advocates have expressed hope.

“We are on the cusp of seeing another push, a more aggressive push at the state level to protect affordable access to contraception, just like we saw in the late ’90s,” Andrea Miller, president of the National Institute for Reproductive Health, told the New York Times in June after a draft of the rule was made public. “The feds can set a floor. States can decide to do better.”