<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-196498139/stock-photo-a-river-with-some-buildings-next-to-it.html?src=pyk/O8dvcl/TkA7yy99RqA-1-10">Stacey Newman</a>/Shutterstock

A while back, I wrote about how the US Environmental Protection Agency has been conducting a slow-motion reassessment of a widely used class of insecticides, even as evidence mounts that it’s harming key ecosystem players from pollinating bees to birds. Since then, another federal entity with an interest in the environment, the US Geological Survey, has released a pretty damning study of the pesticide class, known as neonicitinoids.

For the paper (press release; abstract) published last week in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Pollution, USGS researchers took 79 water samples in nine rivers and streams over the 2013 growing season in Iowa, a state whose vast acreage of farmland is largely devoted to neonic-treated corn and soybeans. Neonics showed up in all of the sites, and proved to be “both mobile and persistent in the environment.”

Levels varied over the course of the season, spiking after spring planting, the authors report. At their peak, the neonic traces in Iowa streams reached levels well above those considered toxic for aquatic organisms. And the chemicals proved to linger—the researchers found them at reduced levels before planting, “which indicates that they can persist from applications in prior years,” USGS scientist Michelle Hladik, the report’s lead author, said in the press release. And they showed up “more frequently and in higher concentrations” than the insecticides they replaced, the authors note.

Other studies have shown similar results. Neonics have shown up at significant levels in wetlands near treated farm fields in parts of the High Plains and in Canada, as wells as in rivers in ag-heavy areas of Georgia and California.

These findings directly contradict industry talking points. Older insecticides were typically sprayed onto crops in the field, while neonics are applied directly to seeds, and then taken up by the stalks, leaves, pollen, and nectar of the resulting plants. “Due to its precise application directly to the seed, which is then planted below the soil surface, seed treatment reduces potential off-target exposure to plants and animals,” Croplife America, the pesticide industry’s main lobbying outfit, declared in a 2014 report.

Yet the USGS researchers report that older pesticides that once rained down on the corn/soy belt, like chlorpyrifos and carbofuran, turned up at “substantially” lower rates in water—typically, in less than 20 percent of samples, compared to the 100 percent of samples found in the current neonic study. Apparently, pesticides that are taken up by plants through seed treatments don’t stay in the plants; and neonics, the USGS authors say, are highly water soluble and break down in water more slowly than the pesticides they’ve replaced.

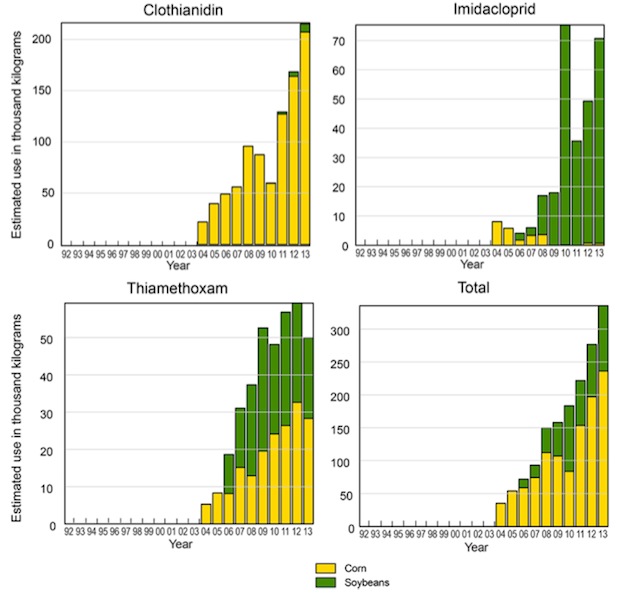

In another document, Croplife claims that neonicotinoids “have been used in the United States for many years without significant effects on populations of honey bees.” But the paper shows that neonic use didn’t start in the heart of corn/soy belt until 2004, and then quickly ramped up. The below graphic, lifted from the paper, shows usage data on the three major neonic chemicals, with the chart on the bottom right depicting total use. According to the USDA, colony collapse disorder started in 2006. Correlation doesn’t prove causation, but the industry’s “many years without significant effects” claim doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

In leaching from farm fields, neonics follow a pattern established by spray-applied herbicides like atrazine, the authors note, which undergo a similar “spring flush” into waterways. That means that each spring in Iowa, critters like frogs and fish find themselves immersed in a cocktail of damaging chemicals.

Meanwhile, the use of seed treatments is surging—it tripled over the past decade. And not just neonics. Fungicides—chemicals that kill fungal pests—are also being applied to seeds at record rates. According to Croplife, “today’s seed treatment market offers pre-mixture products containing combinations of three, four or more fungicides.” It also boasts: “The global fungicide seed treatment market is growing at a compound annual growth rate of 9.2 percent and is expected to reach $1.4 billion by 2018.”

And these chemicals, too, are emerging as a threat to honeybees. They also may be fouling up water. In 2012, the USGS released a research review on fungicides and their effect on waterways. The report noted plenty of “data gaps”—i.e. a dearth of research—but also evidence of “significant sublethal effects of fungicides on fish, aquatic invertebrates, and ecosystems, including zooplankton and fish reproduction, fish immune function, zooplankton community composition, metabolic enzymes, and ecosystem processes, such as leaf decomposition in streams, among other biological effects.”