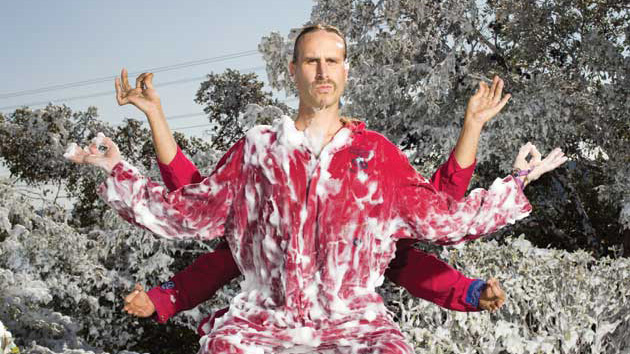

David Bronner, CEO of Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps, presides over a company with famously wacky product labels. Sample sentence, from the 18-in-1 Hemp PEPPERMINT soap bottle: “Each swallow works hard to be perfect pilot-provider-teacher-lover-mate, no half-true hate!” But Bronner himself, grandson of the founder (the one with the elaborate prose style), has emerged as a serious, though fun-loving, activist, particularly around pesticides and genetically modified crops, as Josh Harkinson’s recent Mother Jones profile shows.

But apparently, Bronner’s writing on GMOs is too hot for the advertising pages of the English-speaking world’s two most renowned science journals, Science and Nature—even though a slew of magazines, including Scientific American, The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Nation, Harvard, and, yes, Mother Jones, accepted the Bronner ad. It consists of a short essay, known in publishing as an advertorial, that’s nothing like the wild-eyed rants on his company’s soap bottles. Bronner’s ad (PDF) focuses on how GMO crops have led to a net increase in pesticide use in the United States, citing an analysis by Ramon Seidler, a retired senior staff scientist at the Environmental Protection Agency.

Bronner wrote his essay in response to Michael Specter’s recent New Yorker takedown of anti-GMO crusader Vandana Shiva. He first published his critique on Huffington Post, and then decided to publish it as an ad in a variety of high-profile magazines, because he felt that The New Yorker is highly influential among liberal elites, and he wanted to get his dissenting view out, he told me.

Science was close to accepting it, emails shared with me by Bronner show—an ad sales manager for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which published the magazine, emailed on September 15 that she would send over paper work “in a bit,” adding that “[a]fter you sign it, I can take your credit card info by phone and submit to accounting.” The price: $9,911.00. But hours later, she wrote back, squashing the deal:

Sorry to say there has [been] a reversal opinion. This has gone up the ladder quite far and our CEO along with the board have come back saying that we cannot accept the ad. We’re concerned about backlash from our members and potentially getting into a battle with the GMO industry.

Something quite similar happened at Nature, a UK-based publication with ad sales operations in the United States. On September 16, an ad sales rep told the Bronner team via email that “I will have an IO [insert order—the contract for an advertisement] for you once I get the thumbs up from Editorial (usually takes them a day or two).” Once that’s signed, he added, “I can call and get your credit card information over the phone, [and] then we are all good.”

But a few days later, instead of closing the deal, the rep asked if Bronner would consider placing the ad in a smaller, related journal called Nature Biotechnology. Bronner declined, and asked again to place it in Nature. The ad rep replied, “We have to do a detailed process for all ad approvals, especially if the ad is not within specs (our terms and conditions). We have passed on the ad for Nature, that’s why the emails about seeking out other options [i.e., Nature Biotechnology] for you.” End of discussion—the sales rep offered no explanation, and soon stopped returning calls or emails. Nor did he return my email and call seeking comment.

As for Science, I talked to Laurie Faraday, the journal’s East regional ad-sales manager, who worked with Bronner’s team on the failed ad deal. She explained that the editorial side weighs in on decisions over advertorial-style ads. Science‘s management found it “a little bit controversial,” and worried that “if we allowed that kind of a piece to be printed in Science, then maybe we’d be subject to the GMO world coming after us.” She added: “Ironically, it’s not that anyone in the organization disagreed with what it [the ad] said. It’s just that we had to consider that the opposite side of the coin might want to start a war in our magazine.”

I asked if the magazine had rejected advertorials on similar grounds in the past. She replied that a couple of years ago, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals ran ads in Science alleging cruelty to animals in labs. “It kind of got past us at first,” Faraday said, “but after the campaign ran, I was told by the publisher we would not accept them any further.”

Stan Schmidt, an ad rep for Scientific American, which accepted the ad, told me that his magazine has a broader policy on advertorials—it accepts them unless they contain offensive or “wild-eyed” material, and the Bronner ad easily passed the test, he said.

“I’m concerned how lame and weak the leading scientific publications in the world are being here, although I appreciate Science‘s upfront explanation,” Bronner said. “Science and Nature magazines, like the scientific enterprise in general, are not above the fray.”