Bernie Sanders speaks during a campaign event in Spartanburg, South Carolina, on Thursday, February 27.Matt Rourke/AP

In the ballroom of a convention center in Columbia, South Carolina, Bernie Sanders campaign co-chair Nina Turner stared out at the crowd of supporters that had gathered for what they’d hoped would be another victory party. The group was much smaller than the ones who’d flocked to see her and Sanders throughout South Carolina that week, but it did share one key characteristic with its predecessors: It was mostly white.

And that was precisely the problem for the Sanders campaign in a state where two-thirds of the primary electorate is Black.

Former vice president Joe Biden didn’t just win South Carolina—early results show he swept every county and nabbed nearly half of all votes cast. Exit polls suggest Biden had support from 61 percent of Black voters, compared to Sanders’ paltry 17 percent. Turner, who had been the lifeblood of Sanders’ outreach, told supporters in the ballroom that Sanders, according to early internal numbers, had won voters under 44 years old, young Black voters by 40 percent, and first-time voters by 30 percent. But the reality was clear: Sanders had barely beaten his 2016 showing in the Palmetto State, when Hillary Clinton crushed Sanders.

It surely wasn’t what the campaign had envisioned. After victories in New Hampshire and Nevada and winning the popular vote in Iowa, Sanders had been bullish about his South Carolina prospects. He entered the early contests telling supporters he would do “better than they thought” in South Carolina; in recent weeks, he began saying he might win.

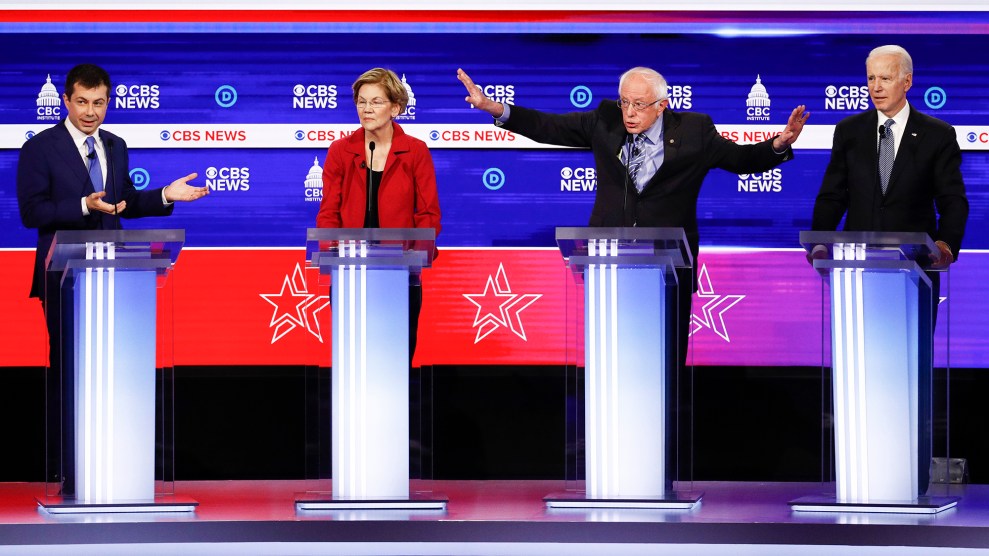

There were signs that Sanders optimism hadn’t been unfounded. While polls of the state had Biden with a massive lead over the rest of the field for much of the 2020 campaign, Sanders caught up to him after his early victories. All week, national media had been touting Sanders’ efforts to court the state’s Black voters—particularly younger Black voters, who had shown a preference for Sanders’ liberal stances and record on fighting for civil rights. All across the state, I encountered voters who suggested the strategy might be working. Melinda Williams, who canvassed for Sanders in the poor black neighborhoods of Sumter, told me she’d converted some Biden voters to Sanders after explaining that Sanders had attended Martin Luther King’s 1963 March on Washington and supported Jesse Jackson’s 1988 racial justice and poverty-centered run for president. Tracie Blue sat through a 45-minute roundtable that Pete Buttigieg held with Black community leaders in Greenville on Thursday, before telling me she was thinking about voting for Sanders. “He’s been in the trenches,” she said. “He has been fighting for us and our rights as a people for a very long time.”

Four years ago, Sanders had been criticized by Black Lives Matter protestors who scoffed at Sanders for failing to explicitly recognize the racial injustice at the base of economic inequality facing Black Americans. This time around, he seems to have taken their concerns seriously. During his last run for the White House, Sanders rejected the idea of reparations for descendants of the formerly enslaved as too unrealistic and politically divisive; this cycle, he’s embraced legislation to study and develop a reparations proposal. His economic justice plans have been strengthened with a racial justice lens, such as his proposal to boost marijuana businesses led by minority entrepreneurs—and he’s done so in consultation with scholars who have pioneered the study of the racial wealth gap. The class-centric rhetoric remains in his stump speeches, but he talks about race more than he used to—and a deep bench of new and returning Black surrogates bridge that gap when Sanders fails to.

“’Soviet,’ ‘communist,’ ‘Bolshevik,’—that’s what they said about my brother, Martin Luther King, Jr,” the scholar and activist Cornel West told a crowd in Columbia last Saturday to assuage fears that a democratic socialist label would harm Sanders in a general election.

What holds Sanders back from toppling Biden altogether? Older voters—who are also the likeliest voters—are a piece of it, a problem that persists from this 2016 run. Clay Middleton, who worked for both Obama and Clinton in South Carolina and served as a senior adviser to Cory Booker’s campaign, blames Sanders’ unpopularity among them on a lack of retail politics. When Sanders visited the Palmetto State, he favored large format rallies and town halls over intimate gatherings; an analysis from the Charleston-based Post and Courier lists just about a dozen roundtables and meet-and-greets over the 41 campaign stops he’s made over the last two years. “I think older people feel like Bernie is yelling at them,” Middleton says. “Because he does not do any retail politics, older folks doesn’t feel like he comes across as a warm person.”

Another factor might be the derision Sanders has faced from establishment African American political leaders in the state. On Wednesday morning, James Clyburn, the influential black congressman considered the state’s Democratic kingmaker, endorsed Biden. Preliminary exit polls suggest at least half of South Carolina voters say Clyburn’s endorsement influenced their vote.

National polling suggests Sanders is doing better with Black voters than his outcome in South Carolina might suggest. An NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll from mid-February showed Sanders gaining ground, about equal to Biden in terms of Black voters. A Hill/HarrisX poll conducted the week before South Carolina found that Sanders surpassed Biden nationally in Black support.

Still, Saturday’s results could be a problem for a campaign staring down several Southern states on Super Tuesday, where candidates will similarly face a majority-Black Democratic electorate.

State Rep. Justin Bamberg, a Sanders supporter, thinks the South mentality is one less inclined to accept Sanders’ calls for radical change. Old black voters in particular, he says, distrust the federal government, a belief that runs counter to Sanders’ promises of overhauling it. And the faith in reliable, trustworthy institutions like Rep. Clyburn poses an obstacle to turning the tide in Sanders’ favor. Bamberg tells me the counter is to remind folks that the federal government has served Black South Carolinians well—and that’s true more than ever in a state where states’ rights have been ruinous for women who want control over their bodies and workers who want to organize.

“It’s difficult to maintain an open mind, particularly in the South,” Bamberg says, noting how schools, churches, and community spaces remain segregated decades after the Civil Rights Act’s passage. “Its foundation is built on resisting change—and that shit’s gotta stop.”