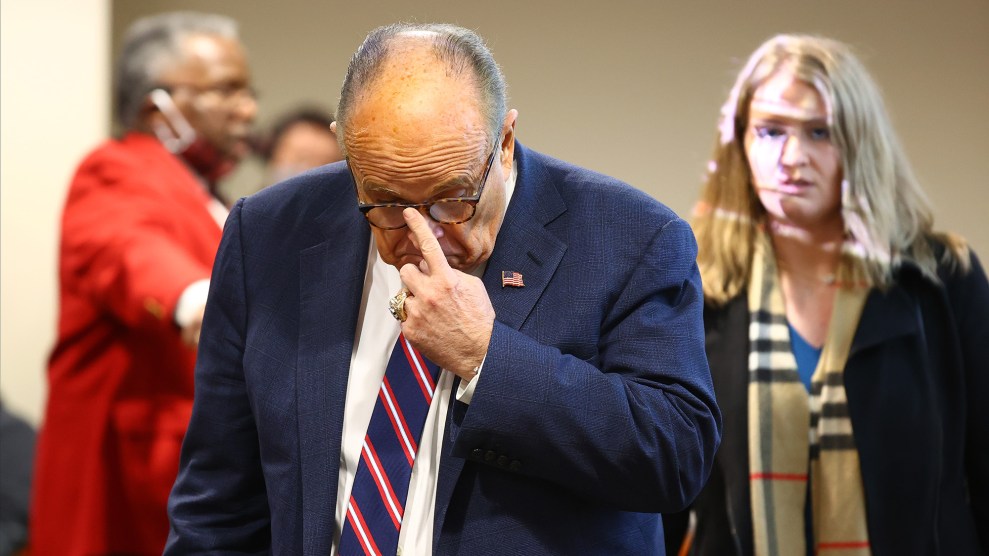

President Donald Trump's personal attorney Rudy Giuliani arrive for an appearance before the Michigan House Oversight Committee on December 2, 2020 in Lansing, Michigan. Rey Del Rio/Getty Images

It may seem fitting that 2020 is ending with a parade of lawyers filing conspiracy-theory-laden, error-riddled, and legally unsound lawsuits in an effort to overturn the results of November’s election. With a vanishing chance of success, the antics are even funny, easy fodder for Saturday Night Live. But like so many other episodes of the Trump era, we may be witnessing another democratic institution wither in the face of anti-democratic pressure.

Thus far, courts have unceremoniously rebuffed Republicans’ fraud allegations, seeing through their failure to prove ballot-box-stuffing, voting machine manipulation, and various other accusations. “Allegations that find favor in the public sphere of gossip and innuendo cannot be a substitute for earnest pleadings,” a federal judge in Arizona wrote in tossing out an attempt to overturn the state’s election results, adding that the claims are “sorely wanting of relevant or reliable evidence.” In Michigan, a judge found Republican claims of fraud “incorrect and not credible.” In Nevada, a judge found that Trump electors seeking to overturn that state’s results did not provide proof of fraud that met “any standard of evidence.” And yet, dozens of these irresponsible lawsuits have been filed across the country. Some could drag on for several more weeks, even after Monday’s Electoral College voting makes Joe Biden’s victory all but official.

Just as doctors swear an oath to protect their patients—and lose their medical licenses if they harm patients—lawyers, too, are supposed to abide by ethical standards. Every practicing attorney is licensed by a state bar, and every bar has ethics rules. If a state bar receives a complaint against one of its lawyers, it investigates it and can levy sanctions. The most serious sanction is disbarment. So when Trump’s lawyers—Rudy Giuliani and Jenna Ellis—allege massive fraud and help organize lawsuits to overturn the election without compelling evidence; or when pro-Trump attorney Sidney Powell files multiple suits alleging an international voting machine conspiracy; or when attorneys across the country file cases on bizarre legal grounds, I’m left to wonder: Can they do that?

The answer is pretty clearly no. But that doesn’t mean anyone is going to stop them. And if state bars don’t act, it could spell serious trouble for future elections. The lawsuits being tossed out of court each day—as of this writing, pro-Trump lawyers have a 1-59 post-election win-loss record, according attorney Marc Elias, who has represented Democrats in many of these cases—probably won’t overturn the 2020 election. But there’s no guarantee similar tactics won’t succeed next time around. And regardless, the endless parade of frivolous litigation has already undermined faith in the democratic process. One way to ensure that elections do not regularly become mired in bogus court cases is to sanction the lawyers who bring these suits.

“This is the most extraordinary event, as a matter of legal ethics, and as a matter of democratic integrity, that I think any of us have experienced,” says Scott Cummings, a legal ethics expert at UCLA School of Law. “If the bars cannot find the political will and resources to do something about that, then they are really risking their legitimacy.”

The dozens of lawsuits in federal and state court seeking to overturn the election have fallen into roughly two groups. There are the legally absurd, such as the Trump campaign’s lawsuit, argued by Rudy Giuliani, to have Pennsylvania’s election results thrown out over supposed improprieties in mail-in voting. Federal Judge Matthew Brann dismissed the suit, writing, “This court has been presented with strained legal arguments without merit and speculative accusations…unsupported by the evidence.” Second, there are the full-blown conspiracy theory lawsuits. In Arizona, two lawsuits were filed alleging, falsely, that Sharpie pens used by Republican voters were not processed by vote-counting machines. And across the country, Powell has filed, again without evidence, lawsuits alleging an international scheme to use machines from the company Dominion to switch votes from Trump to Biden.

For all these cases, the rules against them are pretty clear. The American Bar Association’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct, which are adapted in some form by every state bar, states that a lawyer shall not bring a suit “unless there is a basis in law and fact for doing so that is not frivolous.” Despite this rule, lawyers for Republicans have filed numerous cases based on hearsay, debunked rumors, and unreliable affidavits. While lawyers do not need to verify the veracity of every affidavit, the track record here is clearly one of frivolity, not a one-off error.

These cases could also run afoul of other legal ethics rules. One prohibits conduct “involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation” or “that is prejudicial to the administration of justice”—a provision that David Luban, an ethics expert at Georgetown University Law Center, describes as an “all-purpose ethics rule that prohibits deceitful and dishonest conduct.” A series of unsubstantiated lawsuits intended to overturn a legitimate election and breed distrust in the democratic process appear would appear to be a textbook violation. “It just seems like there is so much deceitfulness and dishonesty going on in these cases that this is pretty clearly unethical,” says Luban.

In recent days, a number of prominent legal voices have spoken up. In Slate, the four co-authors of the leading textbook Legal Ethics called for sanctions against the lawyers involved. Such sanctions could range from reprimands to suspension and disbarment. In the Washington Post, 25 former presidents of the DC Bar admonished pro-Trump lawyers for becoming “the instruments of a wholesale attack on the integrity of the democratic process.” An open letter published on December 3, arguing that state bar associations need to “condemn this abuse and bar disciplinary authorities need to investigate it,” has received more than 4,100 signatures from lawyers, including from former judges, professors, and local officials. Rep. Bill Pascrell (D-NJ) filed ethics complaints against Giuliani and 22 other lawyers working with the Trump campaign, seeking their disbarment in five states.

This attention to the ethics of the situation gives Cummings of UCLA—a co-author of the Legal Ethics textbook and Slate article—hope that bar disciplinary committees will take action. “My optimism really stems just from the fact that this issue is continuing to be out there,” he says. “Important people like these former bar leaders are continuing to speak out. And I think that matters.” Cummings also believes that the stakes are high and thus demand action. If ethical violations are not investigated and “condemned as out of bounds,” he warns, “then it’s just not clear where we go from here. And if these kinds of lawsuits are just going to become normal for elections in the future, that would be a pretty scary place.”

Mark Tuft, a legal ethics expert in California, expressed faith that disciplinary committees would take complaints seriously and investigate them, and he noted that in the past, state bars have brought in reinforcements to deal with high-profile cases. The OJ Simpson trial, for example, prompted a flood of complaints against counsel on all sides. To handle the deluge, the California bar enlisted the help of outside experts. Tuft was one of those people. (In the end, the bar “imposed only minor discipline for two relatively insignificant infractions,” according to Erwin Chemerinsky, who also consulted on the matter.)

Other ethics experts, however, are doubtful that sanctions are on the horizon. “If history is any guide, it’s extremely unlikely that any of these lawyers are going to face disciplinary sanctions,” says Deborah Rhode, an ethics scholar at Stanford Law School and another co-author of Legal Ethics. “The bar is just, historically, extremely reluctant to take on anything that isn’t a clear, easily provable violation of disciplinary rules, and that has any kind of political overtones.” Moreover, she notes that bar disciplinary processes are underfunded and overworked. This issue came up in multiple conversations with experts: a lack of funding, expertise, and political will to investigate established or high-profile lawyers. “I think if you had a more robust disciplinary process with the likelihood that there would be professional consequences, that would be significant, that would be a deterrent,” she says. “But we’re a long way from that process.”

“This has been a persistent complaint that a lot of people in the legal ethics world have made about our discipline systems for years, which is that they don’t work that well,” says Luban. Most bar complaints do not lead to public sanctions, and that’s particularly true for the well-connected. It’s easier for underfunded committees to sanction solo practitioners, but they leave the big fish largely untouched.

The reason the pro-Trump lawsuits have repeatedly failed is because judges in both state and federal courts have recoiled at the idea of overturning an election, particularly based on unsubstantiated claims. Even Republican-appointed judges have issued harsh opinions in dismissing these cases. Some judges have invited the opposing parties to seek attorneys fees from those trying to undo the election, a sign that the suit is considered without merit. In Arizona, one lawsuit filed to overturn the results was withdrawn after a lawyer for the secretary of state warned the plaintiffs’ attorney that his office would seek attorneys fees. Federal judges can sanction lawyers in the form of a fine or other directive for filings that are frivolous, false, or presented for an improper purpose, but none have taken that step in these cases.

“Is our system failing?” asks Luban. “It’s really under a lot of stress, but at least so far the safeguards have held. A panel of three conservative Republican-appointed judges unanimously says, this is just junk you’re bringing to us,” he adds, referring to a blistering Third Circuit Court of Appeals opinion that essentially put an end to one of the Trump campaign’s efforts to overturn the results in Pennsylvania.

“The thing that we have seen over the last four years is that a lot of this is about law, but a lot of it is about norms and support for norms and principles and values that are really the foundation of our systems,” says Cummings. Now that same question is being put to the legal community, another pillar of our system of government. If filing dozens of frivolous lawsuits to overturn an election and undermine American democracy doesn’t lead to professional consequences, then what’s to stop it from happening again?

Thinking about whether the legal system is holding its own under the pressure of these suits, “my own mental image is a bungee cord that’s stretched to the max and so far, it’s held,” Luban says. “A bungee cord with a safe at the end of it about to fall on the entire republic.”