Photo: Benjamin Loyseau

Read also: MoJo‘s review of the new Benazir Bhutto documentary, Bhutto.

When Fatima Bhutto was just a precocious little girl with “a mouth that never stopped running,” family members often commented on her similarity to her aunt, Benazir Bhutto, Pakistan’s first—and so far only—female prime minister, assassinated in 2007. “‘You’re just like your aunt’ was often used as both a compliment and an admonishment,” writes Fatima in her new memoir, Songs of Blood and Sword. She’d likely be insulted by the same comparison today. Now an author and journalist based in Karachi, Fatima as an adult is one of Benazir’s most outspoken critics. She now characterizes her aunt as an arrogant, manipulative leader who climbed to power without any plan of what to do once she got there.

But her criticism comes paired with an old family grudge: Her father, Murtaza Bhutto, was also a political activist in Pakistan. Unfortunately for the Bhutto dynasty, Murtaza’s views diverged sharply from Benazir’s, and he spent much of his life in exile. In her memoir of the Bhutto family soap opera, Fatima spins an alternative history of the clan and Benazir’s troubled times as prime minister.

Fatima’s no Kennedy; she denies having political aspirations. Nonetheless, she remains loyal to improving Pakistan—even if it is, as she puts it, “a nuclear state that cannot run refrigerators.” She spoke with Mother Jones recently about feminism, Egypt, and the ongoing plight of the Pakistani flood victims.

FB: You know, I can’t overstate how much I hope that would be the case.

Mother Jones: Do you think that the recent unrest in parts of North Africa and the Middle East could spill over into Pakistan? Have you seen any signs of this?

Fatima Bhutto: You know, I can’t overstate how much I hope that would be the case. We haven’t seen any rumblings in Pakistan just yet, it hasn’t seemed to reach people in the way that it’s spreading across North Africa and the Middle East, but you know the parallels are incredible. These are generations of Tunisians and Egyptians, for example, who have known nothing but the Ben Ali family, the Mubarak family, in the same way my generation of Pakistanis have come of age in the era of dictatorships. We have only known military dictators or corrupt civilian autocrats. We have more than one name, maybe three, where the face has changed but the policy has stayed the same: the ability for the state to impose emergency rule on its people, the ability for the state to censor and to hinder the liberty of its citizens is incredibly familiar.

But it hasn’t happened in Pakistan yet, so of course all of the objective conditions exist. And is it because Pakistan is a country reeling at the moment? We have the most disastrous natural disaster in our history, in 80 years; we hadn’t seen anything like the floods that hit the country this fall and winter. Twenty million people were affected. We’re also an international battleground; some 2,000 Pakistanis have been killed in drone attacks in the last two years, largely civilians. You know we have a government that takes great support and great strength from foreign power. Are these the factors that are keeping people from reacting as they are in Egypt and Tunisia? I don’t know, but I certainly hope that they can be overturned.

MJ: I just finished your new memoir, Songs of Blood and Sword. Besides fitting a lot in the book about the history and politics of Pakistan, you’ve tried to recreate the life of your father Murtaza, who was assassinated in 1996. In the forward, you quote Milan Kundera, who said: “The struggle of people against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting,” and then you say, “This is my journey of remembering.” I was wondering if you could tell me about the journey of researching the book, and whether it was ultimately cathartic for you?

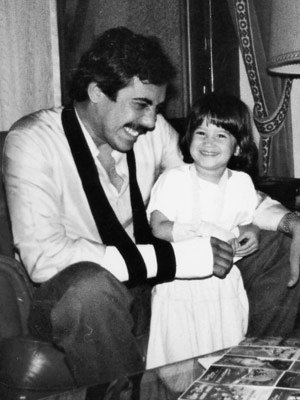

FB: Well, it was a journey that took me very much outside of our family home in Karachi and I retraced my father’s youth, really, from his college days in the states to his time campaigning to save his father’s life in England and around the world, his move to Afghanistan, his time in exile, and then ultimately his return home, and his decision to enter politics, contest the election, and find the family again in Karachi, again in a scene that would seem very familiar: more politics, and certainly more violence.  Fatima as a child with her father, Murtaza Bhutto. Photo courtesy Fatima Bhutto

Fatima as a child with her father, Murtaza Bhutto. Photo courtesy Fatima Bhutto

MJ: What have been some of the reactions to your book? Have you had any surprising ones?

FB: I was very pleased to see actually—in a country where silence has become just as much a part of the political ethic as violence—people’s openness and curiosity and ability to speak about these twin phenomenons, this repetitive cycle of dynasty and violence. Not surprisingly, of course, was anyone associated with the ruling government’s reaction. It’s almost impossible for them to claim that they are not known for their corruption or that they don’t have an enthusiastic and flexible hold on violence. So the only way [for them] to respond to the book, I suppose, was to pretend that it doesn’t conform to their sense of reality. But had they reacted differently, I would have been surprised.

MJ: I also just watched a recent documentary called Bhutto, and you’re interviewed in it, and you allege that Benazir and her husband Asif Ali Zardari had a hand in assassinating your father, Murtaza. Since the release of the documentary, and the release of your memoir, have any more clues surfaced that point in this direction? I’m kind of interested in the aftermath of that allegation.

FB: Well I haven’t seen the documentary, and in fact, it seems to have been a Zardari family vehicle, so I can’t comment on that. But this is a case that has been in the Pakistani courts for the last 15 years. What we keep seeing, though, is this inability of the Zardaris to distance themselves from the murder. On his first day as president, Asif Zardari awarded a National Medal, a Hilal-e-Imtiaz, to one of his co-accused in the murder case, a man called Shoaib Suddle. And he gave him a national medal for services to Pakistan. Just two weeks ago, we’ve seen that another one of the president’s co-accused in the murder cases, a police officer called Wajid Durrani who was instrumental in the choreography of the murder, has just been promoted to the inspector general of the Islamabad police. So all those who are associated and who were accused, along with President Zardari in the murder case, seem to be very close to government still. They seem to be promoted and celebrated on a national and federal level, without any attempt by the president to distance himself from those who he is connected to, at least in the prosecution’s mind in my father’s murder case.

MJ: And you write about how Benazir had a “conflicting and divergent” personality. What misconceptions do you think people have about her…maybe that Americans would have about her?

FB: I think maybe the strongest way to look at the contradictions in Benazir the icon and Benazir the politician, are three things. The first would be: this notion that she was a democrat. In the West, people believed that she was a symbol of democracy, yet within Pakistan, she had declared herself the chairperson for life of her own party. In the 20-odd years of her leadership with the PDP, not one internal election was held.

The second, I guess would be that she was a feminist, that she somehow spoke for women’s rights. And again we see a very different reality, which is that in two terms as a prime minister, Benazir does not remove the Hudood Ordinances. And the Hudood Ordinances are the most violent laws against women in Pakistan: They are the laws that say a woman who commits adultery can and should be put to death, and that any woman who engages in premarital sex can and should be put to death, effectively criminalizing the victim of rape. So Benazir as a two-term prime minister didn’t cut those laws, didn’t remove them.

And I suppose the third misconception was that she was a liberal, and again, the reality was very different. It was during Benazir’s last government that the Taliban in Afghanistan were supported and certainly acknowledged by Pakistan. When the Taliban took over in 1996, only three governments in the world accepted to do business with them: Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Benazir’s Pakistan.

MJ: Do you think Benazir was trying to stand up against Islamist pressures, or was she more in cohort with Islamist leaders?

FB: Well, again, if we look at the ground reality and the political fact, it would show that in fact she had electoral alliances with Islamic parties, which you know until 9/11 were really incredibly weak: They had no political strength in Pakistan, but they were always election allies. The refusal to cut the Hudood Ordinances, the refusal to remove the Blasphemy Laws, for example, can only be interpreted as a matter of appeasing the Islamic factions, and Benazir was also the first woman in her family to wear a veil. She came from a secular, liberal background where no one in her family covered their head. And she seemed to surround herself, if not actually, politically with a sort of acquiescence towards more religious, fundamentalist ideas with a symbolism of religion, as if to comfort those who might suggest that she was too modern or too liberal.

MJ: Back to your book. It struck me that it’s really a book about exiles. Your father was in a constant state of migration, and you even grew up in Damascus. Is Pakistan the country that you most identify as home?

FB: Yes, Pakistan’s the country that I sort of dreamed of and lived spiritually or mentally long before I ever set foot in it. And even though there are many different places that I’ve called home over the years, I suppose I like what the poet Rumi said, which is: “Though one wanders and one travels, my compass always points towards home.” And that home is Pakistan.

MJ: What’s going on right now in Pakistan, in terms of building the country back up after the flooding?

FB: Entirely nothing, it would seem. What we know is that 20 million people were directly affected. We know that the United Nations said that the scale of the disaster was worse than the Haitian earthquake, the Asian tsunami, and the 2005 Pakistani earthquake combined. And what we’ve seen on the ground is that when government officials have gone to visit flood-affected areas, they were physically assaulted, you know, according to networks like the BBC.

The government has come up with a system of Watan cards, which are cards that are given to flood-affected families that they then have to take to an ATM. And most of the regions that were affected by the flood are in the countryside, they are not places that have coffee shops and ATM machines. Now again, what we’ve seen from the Watan card scheme so far is suggestions of malfeasance and suggestions of corruption. The families who have been given the Watan cards have said that when they have managed to go and receive the money—which again is nominal in terms of compensation—they’ve been told that the money was already taken out of their accounts. You hear of course, again through vehicles like the BBC, of families in one area that have all received Watan cards, and families in another that have received none.

So the world, I think, seems to have disconnected from the plight of the Pakistani flood victims very early on, and that makes it even harder to push for some kind of transparency, especially with a government that is notoriously corrupt.

MJ: As you’ve drawn attention to in your writing, the US has supplied Pakistan with billions of dollars to fight terrorism in the last decade, but the US has also been behind the drone attacks which have had a 21 percent civilian casualty rate since 2004. How do the Pakistanis you know feel about the American government at this point?

FB: I think, again, if we look back to the floods, what we saw was that at the time of Pakistan’s greatest need, and you know, just unparalleled disaster around the country, with one hand America gave aid, with one hand they gave Chinook helicopters and financial aid, and with the other hand they launched the most extensive drone campaign against the country in the last six years. So September 2010, the month after the floods, was the heaviest in terms of drone strikes, some 21 strikes in 30 days.

So America is seen as a government at this point—the American government rather—though it may speak of values such as democracy and censorship, they have been consistent in enabling and supporting not only dictatorships, but civilian autocratic governments who have censored, who have really closed down on the political system in the past three years. And I suppose it’s worth noting that the White House has supported every single military dictator that Pakistan has ever had: economically, financially, militarily, and politically. And that continues, and that colors certainly how Pakistanis view America and its promise of supporting democracy in our part of the world.

MJ: And you’ve been an outspoken critic of Zardari; one of your more recent articles was entitled “Why My Uncle Asif Ali Zardari’s Rule in Pakistan Cannot Be Trusted.” Have you ever been threatened by his leadership to stop writing or speaking out against him?

FB: Especially since Songs of Blood and Sword has come out, there are many ways in which one is reminded of how in his hands one’s life is. I mean, when one of the most senior police officers indicted in my father’s case gets a national medal from the president, that sends a very strong message. This August, my mother Ghinwa was in Larkana, which is where the family comes from, traveling and doing some flood relief work, when her car was shot at. Now, the last time our car was shot at was 15 years ago. You know, governments have come and gone, but of course been aggressive and have been hostile, but one’s car hasn’t been fired upon.

And where do you go when these things happen? The local administration is unwilling and unable to protect the people, the police are part of the process of violence, the courts are in the government’s hands, and the media is going through a period of noticeable self-censorship, if not outright censorship. I think that’s really what makes the situation so fraught and so tense.

MJ: What have you been up to since you finished the book?

FB: I have been on a neverending book tour, which has taken me around Europe and America so far, and the book has just come out in French, so I’ve been traveling. But hopefully I’ll be able to sit down soon and get working on the second project.

MJ: And what’s that? Do you know yet?

FB: I’m hoping that it will be a book on Karachi, it will be a book on one of the most beautiful and I think one of the most frightening cities we have in Asia, certainly, a megacity whose culture is very rich and whose politics is very divisive.

MJ: Well, I would look forward to reading a book about Karachi.

FB: Thank you!