Ed Zurga/AP

As the Kansas City Chiefs and the San Francisco 49ers head to Las Vegas for the Super Bowl on Sunday, Native activists will for the fourth time in five years travel to the stadium where the championship game is played to protest the Chiefs’ name and other racist traditions.

While the NFL’s Washington Commanders (whose name was previously a slur) and Cleveland Guardians (formerly the Indians) have given in to public pressure and changed their monikers since 2020, the Kansas City team—which played in the Super Bowl in 2020, 2021, and 2023—has refused to follow suit. Gaylene Crouser, who leads the nonprofit Kansas City Indian Center, told Native American news service ICT that she especially loathes some of the team’s traditions, such as the tomahawk chop war chants that fans do or the headdresses they still wear, imagery that reminds her of colonial violence against Indigenous people. “Every single game brings trauma for me,” she told the New York Times in 2020.

Rhonda LeValdo, who founded Not In Our Honor, a group opposed to the Chiefs’ name and imagery, said demonstrators this year will also protest the 49ers’ name, which refers to the hundreds of thousands of gold miners who descended on Indigenous land in California in the 1800s, displacing and killing as they went. “I was calling it the Genocide Bowl,” she told ICT. “It’s so weird how Americans celebrate their teams with this.”

The push to change racist NFL mascots stretches back decades. In the 1990s, several Native leaders sued the Washington team over its name, but the suit was unsuccessful. Then in 2020, after Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd, nationwide racial justice protests lent new momentum to the movement. As protesters around the country tore down or vandalized monuments for racist historical figures, they also pressured NFL sponsors: Nike removed the Washington team’s apparel from its website, and Amazon, Target, and Walmart stopped selling the team’s merchandise. Washington caved and became the Commanders, and not long afterward the Cleveland Indians agreed to become the Guardians. “American Indian mascots are harmful not only because they are often negative, but because they remind American Indians of the limited ways in which others see them,” Stephanie Fryberg, a Tulalip psychologist and researcher, wrote in recommendations by the the American Psychological Association, which urged teams to stop using these names. But the Kansas City Chiefs, along with other professional squads like Chicago’s Blackhawks hockey team and the Atlanta Braves baseball team, have not listened.

The Chiefs were once the Dallas Texans, but the owners changed the name in 1963 to honor then-Mayor H. Roe Bartle, who helped bring the team from Dallas to Kansas City, Missouri. Bartle, who was not Indigenous, was nicknamed the “Chief” because he created a Boy Scouts group that dressed in Native-themed attire and wore face paint, according to ICT. Newspaper cartoonist Bob Taylor designed a new logo—a Native man with rock-hard abs, a feather headdress, and a loincloth—and fans listened to powwow-style drumming at games. In 2020, in response to escalating pressure, the Chiefs banned headdresses and warpaint from their stadium, but fans continue to wear them. Owners conferred with a Native advisory group that approved keeping the team’s name, though Crouser of the Kansas City Indian Center says activists like her were not invited to the discussion. “The team has worked hard to put out the illusion that they work with tribes because they do work with a few tribal members,” Crouser told USA Today. “But they weren’t interested in talking to us because they knew what we would have to say.” Kansas City long snapper James Winchester, of Choctaw Nation, told ICT that he does not view the team’s name as offensive, though he recognizes that some Native people do. “I’m just proud to be part of this organization,” he said in 2023. Michael Spears, an actor who is Sicangu Lakota, told USA Today that he perceives the Chiefs’ traditions as appropriation. “People think they’re honoring us with these mascots and logos, but they’re mocking us.”

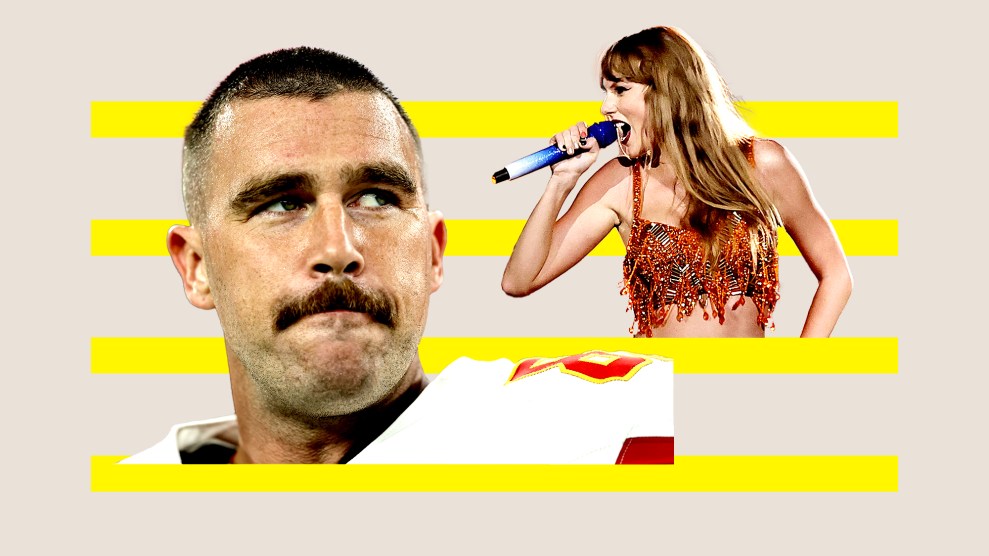

Ahead of the Super Bowl, Ben West, a Cheyenne filmmaker, released the documentary Imagining the Indian: The Fight Against Native American Mascoting, along with filmmaker Aviva Kempner, to raise awareness of the problem. Native activists have even appealed to Taylor Swift, who is currently in a relationship with Kansas City tight end Travis Kelce, to stand up for the cause. Whether football fans will pay attention remains to be seen. “We see people all the time walking past us while we’re standing out there protesting,” Crouser told Yahoo. “They still have headdresses on.”