Mother Jones; Eric Lee/POOL/CNP/ZUMA; Charles Krupa/Getty

In 2017, it took a shooter 10 minutes to spray more than 1,000 rounds into a crowd watching a Las Vegas concert. He murdered 58 people and injured 500 more in America’s deadliest mass shooting. He did this with a bump stock, an accessory that, for all intents and purposes, transforms semi-automatic rifles into machine guns. Today, the Supreme Court’s GOP-appointed justices legalized bump stocks. Any gun owner can now possess this weapon of mass carnage.

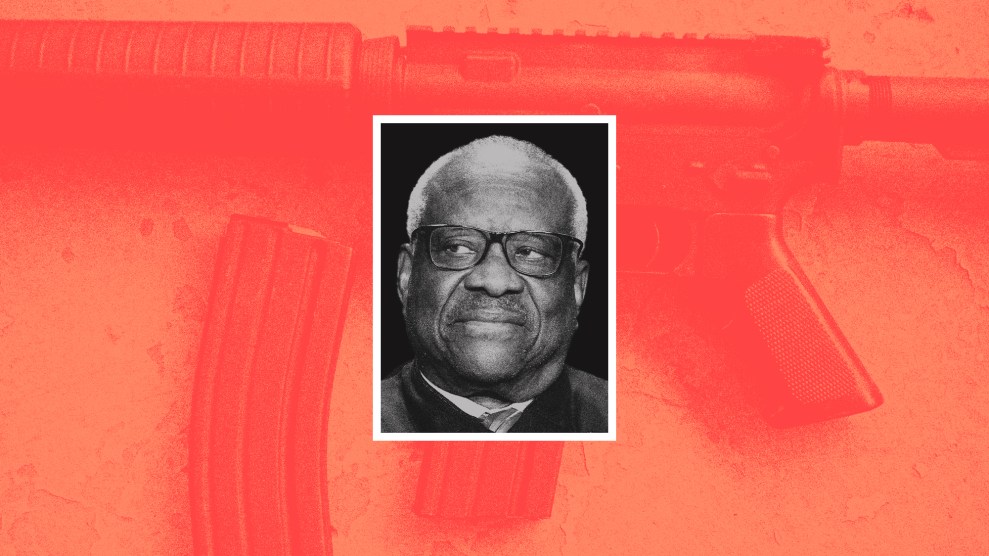

After the Las Vegas shooting, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, under President Donald Trump, and with bipartisan support, reclassified bump stocks as machine guns, which have been banned for decades. But in a 6-3 decision issued on Friday and written by Justice Clarence Thomas, the court ruled that bump stocks are not machine guns and that ATF lacks the authority to prohibit them.

The conservative justices adopt a new definition of machine gun that ignores the statute.

A machine gun is defined under federal law as “any weapon which shoots, or is designed to shoot, automatically . . . more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger.” Crucially, this includes “any part designed and intended…for use in converting a weapon into a machinegun.” Equipped with a bump stock, a semi-automatic rifle can fire an equivalent number of rounds as a machine gun without the shooter pulling their trigger finger multiple times. It does this by harnessing each shot’s recoil to bump the trigger automatically, rather than relying on the manual pull of the shooter, discharging bullets much faster than if a shooter had to use their finger.

Thomas’ argument, adopted by the court’s other Republican appointees, is that this functionality does not meet the definition of a machine gun under federal law because the trigger mechanism is reengaged for each shot—even if not by a manual pull of the trigger. In doing so, he essentially adopts a new definition of machine gun that ignores the text of the statute, which includes components that convert a firearm—like a bump stock.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in a dissent joined by the other two Democratic-appointed justices, notes that Thomas is creating a distinction without a difference. “When I see a bird that walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck,” Sotomayor writes.

Thomas’ opinion reads as if the majority’s hands are tied—that they simply cannot square a bump stock ban with the language of the law. Justice Samuel Alito wrote a concurrence to this effect. Sotomayor finds the notion hollow, accusing her colleagues of abandoning their usual textualist approach: “Every Member of the majority has previously emphasized that the best way to respect congressional intent is to adhere to the ordinary understanding of the terms Congress uses,” she writes. “Today, the majority forgets that principle and substitutes its own view of what constitutes a ‘machinegun’ for Congress’s.”

Thomas’ decision argues that because ATF previously allowed bump stocks, its about-face after the Las Vegas massacre makes the regulation suspect. It also cites a prediction made by the late Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) that the ATF’s regulation of bump stocks would be overturned in court.

But such justifications elide the fact that the ATF reasonably interpreted the law in order to make Americans safer. Agencies may change their minds; there is no rule that once an agency decides something, it must stick to it forever. Notably, in the next few weeks, the court is likely to overrule its own longstanding practice of deferring to reasonable agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes, a principle known as Chevron Deference.

This case does not cite Chevron; neither the majority or the dissenters argued the gun statute’s language is ambiguous. But it clearly is operating in a post-Chevron world, one in which decisions about Americans’ safety are determined not by Congress or the agencies, but by nine justices who don’t even have a binding code of ethics.

Congress tried to ban machine guns, and ATF decided after America’s deadliest massacre that bump stocks created machine guns. Six Supreme Court justices just overruled them. That’s not how the law or democracy are supposed to work. Civilians toting firearms with machine gun capabilities is not the makings of a healthy society—or democracy—either.