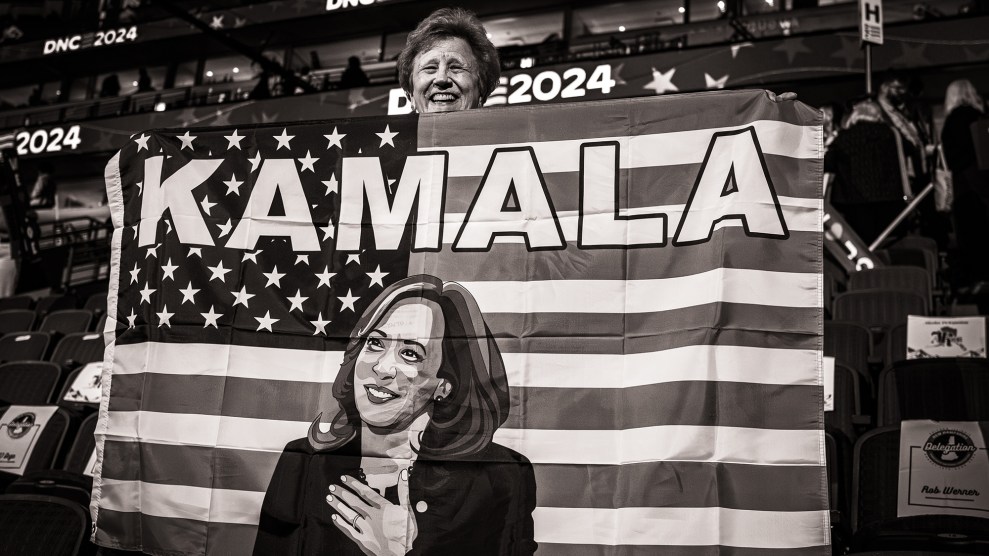

Nate Gowdy for Mother Jones

A name that looms large in Chicago this week belongs to a woman who died 19 years ago.

Shirley Chisholm, the first Black person to run for a major party’s presidential nomination and the first woman to run as a Democrat, is on the lips of delegates and speakers gathered at the Democratic National Convention. Her 1972 candidacy has come to stand for the idea that a woman belongs in the White House. It’s an idea that is on the ballot this year—in more ways than one.

The stakes in this election aren’t symbolic.

“If you don’t have a seat at the table, you are on the menu,” Shannon Watts, the founder of anti-gun violence group Moms Demand Action, said at a convention panel on Chisholm’s legacy. “Women are on the menu.”

It’s a well-worn phrase, but given the choice facing the country, it had an eerie ring: One party hopes to elect the first woman president. The other is coalescing around the idea that women should step away from public life in order to bear and raise children. The hope for a first female president is tempered by the knowledge that losing wouldn’t just be a setback for women in politics, but for women in every corner of the country.

“I know firsthand what’s at stake for women, because I represent the state of Florida, and we have seen essentially the state version of what Project 2025 will be like if, God forbid, Donald Trump ever returns to the White House,” Democratic Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz said. “Extreme MAGA Republicans, led by Ron DeSantis in our state, have enacted a near total abortion ban.”

Under a second Trump term, the federal government would significantly curtail access to abortion, placing limits on women’s ambitions and endangering their health. The administration could undo authorization for abortion drugs, limit access to contraception, and implement the Comstock Act to cut off access to abortion nationwide.

In selecting Ohio Sen. JD Vance as his running mate, the Trump campaign aligned itself with factions on the far right explicitly hoping to redefine women’s role in society. Vance has infamously denigrated “childless cat ladies” for having no stake in the future of the country, and included Harris in that group. He has agreed that the job of post-menopausal women is to help raise their grandchildren.

“If your worldview tells you that it’s bad for women to become mothers but liberating for them to work 90 hours a week in a cubicle at the New York Times or Goldman Sachs, you’ve been had,” Vance tweeted two days after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

When Harris became the Democratic nominee, she immediately and inadvertently represented an opposite notion: that a woman past reproductive age belongs in the White House. But the fact of Harris being a woman is almost incidental. Unlike in 2016, when Hillary Clinton stressed the historic nature of her candidacy and talked about breaking the last glass ceiling in politics, Harris doesn’t dwell on the historic aspect of her campaign.

“The results of this election feel so existential,” Wasserman Schultz explained. “As exciting as it is—and I am really, incredibly excited about the possibility of finally electing a woman president—her gender is just almost like a bonus.”

On Tuesday, delegates and activists mulled about a massive meeting room as music blared, waiting for a morning women’s caucus event to begin. As I spoke to a few, a trend emerged: They had gotten into politics two years ago, after Roe fell. To them, the stakes in this election weren’t symbolic, they were real.

In the days after that decision came down, Cathy Kott of Georgia turned to her daughter, now in her thirties, and said, “I can’t believe I didn’t raise more of an activist.” Her daughter shot back, “What about you?” A few days later, her daughter’s words still ringing in her ears, Kott got a text asking her to run for a seat in the Georgia State House. She signed up.

“When they banned abortion in Missouri, it lit a fire,” says Marsha Snodgrass, a delegate from the state. She got involved in politics for the first time, gathering signatures for a ballot initiative to restore abortion rights there, and two weeks ago agreed to come to Chicago as a delegate.

At a panel on Chisholm’s legacy on Monday, host Juanita Tolliver, an MSNBC political analyst, recounted the two preconditions Chisolm believed were necessary for a woman to become president. The first was that men have time to get used to the idea. The second was that women and young people come together across race and class.

It would take until 2044 for this to happen, Chisholm predicted.

In Chicago, Democrats are hoping she was 20 years off the mark. “I think our time as women, as women of color, has come,” said Alexis Lewis, 70, a Black delegate from California who remembers Chisholm’s campaign. “Women can do more than be wives and mothers.”

It’s a very 1972 debate to be having. But in 2024, it’s alive and well.