One of the most oft-quoted sentences ever penned by a philosopher is George Santayana’s observation that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” In 2024, this aphorism is practically a campaign slogan. Donald Trump, seeking to become the first former president since Grover Cleveland to return to the White House after being voted out of the job, has waged war on remembrance. In fact, he’s depending on tens of millions of voters forgetting the recent past. This election is an experiment in how powerful a memory hole can be.

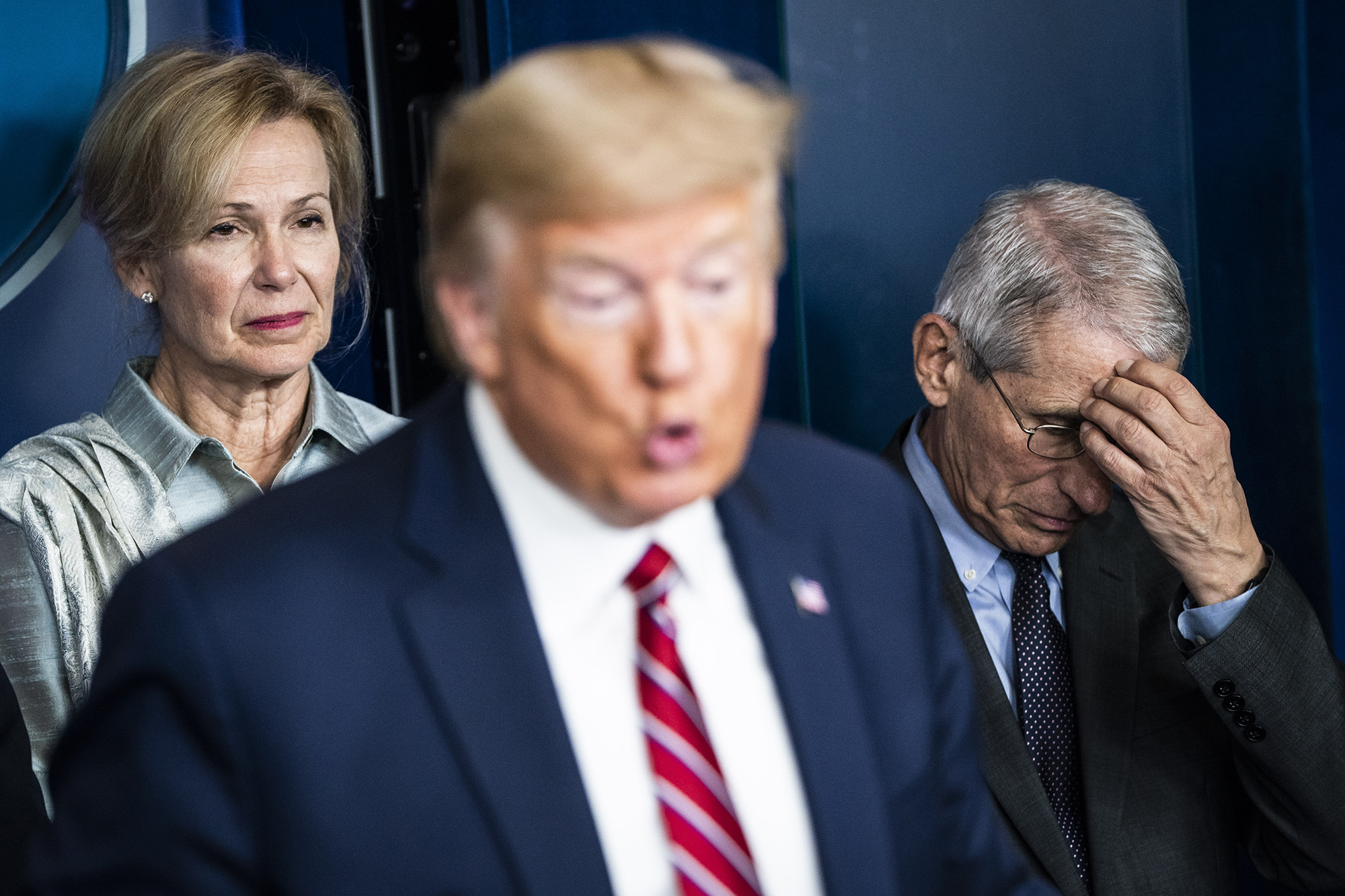

In March, Trump posted this all-caps question: “ARE YOU BETTER OFF THAN YOU WERE FOUR YEARS AGO?” A realistic answer for most would be, hell yeah. Four years prior, the Covid pandemic was raging, the economy was cratering, deaths were mounting, and anxiety was at a fever pitch. Trump responded erratically, downplaying the threat, pushing conspiracy theories, and undermining scientific officials and public health recommendations. (Bleach!) In the final year of his presidency, more than 450,000 Americans died of Covid. A Lancet study concluded the US death rate was 40 percent higher than in similar countries, and that many of those deaths could have been averted had Trump handled the crisis responsibly.

Yet his question—a rip-off of a line used by Ronald Reagan in 1980—assumed many voters would not recall the horror of 2020; he was encouraging them to focus on the sentiments (and high prices) of now, not the mortal dread of then. And to regain the White House, Trump needs to cover not just the pandemic but a lot else with the mists of time, including his attempt to overturn an election and his incitement of January 6’s insurrectionist attack, a trade war with China that cost the US hundreds of thousands of jobs and hundreds of billions of dollars in GDP, his love affairs with dictators like Kim Jong Un and Vladimir Putin, his broken vows to boost infrastructure and to replace the Affordable Care Act with a better and cheaper program, his two impeachments, and nine years of chaos, scandals, and mean-spirited, racist, and ignorant remarks.

That’s a lot of forgetting to rely upon, and the fact that Trump still has a good shot at victory is a sign that he can successfully stuff much of this history into the mental recesses of the electorate. Fortunately for him, the nature of human memory plays to Trump’s favor—even, perhaps especially, when it comes to a pandemic.

Historians have long observed how quickly the so-called Spanish flu of 1918, which killed 50 million worldwide and nearly 700,000 in the United States, vanished from public conversation. As George Dehner, an environmental historian at Wichita State University, observed in his book Influenza: A Century of Science and Public Health Response, “the most notable historical aspect of Spanish flu is how little it was discussed,” resulting in “a curious, public silence.”

“Humans are really good at compartmentalizing things in the past, and Americans appear to be especially good at that. That’s a nicer way of saying we don’t keep track of history very well,” Dehner tells me, explaining Trump is “counting on, and his supporters are cultivating, this tendency to compartmentalize unpleasant associations from the past.”

Guy Beiner, a professor of history at Boston College who edited a 2021 collection of essays called Pandemic Re-Awakenings: The Forgotten and Unforgotten ‘Spanish’ Flu of 1918-1919, notes that today “there is plenty of social forgetting generated in regards to Trump’s presidential term, in particular the mismanagement of the Covid-19 pandemic. It could be argued that such forgetting is typical of post-pandemic societies.”

In August, Weill Cornell Medical College psychiatrists George Makari and Richard Friedman argued in the New England Journal of Medicine that a “collective inability among many people in the United States to remember and mourn what was endured during the pandemic” could help explain why, in early 2024, half of Americans told pollsters they were no better off than they had been “at the height of the deadliest epidemic in the country’s history.” They likened the finding to classic studies by German social psychiatrists that explored how many post–World War II Germans “had seemingly lost the ability to acknowledge the atrocities.” Makari points out that chronic trauma and stress can inhibit memory—and the pandemic yielded much of both. “In addition,” he says, “psychologically this loss of memory is compounded by defenses against helplessness. Finally, socially this is all made worse by collective amnesia. No one wants to remember how terrifying that first year was, before tests, before vaccines. I can barely recall…So from biological, psychological, and social points of views, we grow hazy.”

In a way, this is a mechanical issue. The basic function of memory allows for—or even facilitates—such forgetting, says William Hirst, a New School for Social Research psychology professor. “When you recall the past, you do so selectively,” he explains. “Trump people do that selectively with his agenda in mind.” As Hirst puts it, a narrative that leaves out information “induces forgetting of the unmentioned material.”

“You might think that normally if you don’t mention something, it slowly fades,” he says. “It’s much more dynamic than that.” Talking about other parts of the story actively leads people to forget what is not discussed. So when Trump brags about how wonderful his presidency was and, of course, doesn’t mention the horrors of Covid or the violence at the Capitol, memories of these events become suppressed—but only, Hirst adds, for “in-group members” who see Trump as a legitimate conveyor of information.

“We seem to have a brain that is designed to build a collective memory around collective remembering and collective forgetting,” he explains. “Why? It’s adaptive. We’re social creatures oriented toward our in-group and away from out-groups. Memory is designed to reinforce our in-group membership.”

When Trump falsely says no one was killed during the January 6 riot—which he doesn’t call a riot—and calls the marauders victims and patriots, this shapes the memories of his supporters, according to Hirst, and recollections about brutal facts of that day are smothered. Trump’s repetition—a cornerstone of propaganda—boosts this process. “Each time they hear his account of that day,” Hirst remarks, “the negative part—the breaking-in, the broken windows, the violence—becomes less accessible. And once you suppress the memory image of people breaking in, it’s easier to impose the false memory of protesters having been invited in. There’s no longer a competing memory. So Trump creates this collective forgetting to establish the groundwork for another narrative that is not accurate.”

Certainly, all politicians want voters to forget the negative and remember the positive. President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris do not often discuss 2021’s chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan. Because of that, their supporters may have weaker memories of that event and stronger recollections of the accomplishments Biden and Harris tout.

Trump’s attempts to ride a wave of pandemic amnesia may have been aided by the Harris team’s choice to keep her campaign rollout future-focused. But the foundation was laid long before that, in our lack of any collective narrative about the era. As Makari and Friedman wrote, “Nearly everything about the Covid-19 pandemic is contested: its origins, what could have been done to stop its spread, how politics affected various outcomes, the performance of public health sentries, vaccine science, and the appropriate balance between personal liberties and public health demands. Debates about these issues are often marked by misinformation, tribal allegiances, and rage.” After the pandemic, there was no bipartisan, blue-ribbon panel established—like the 9/11 Commission—that could derive a consensus account of what occurred during that crisis and how it was handled by the Trump administration and others.

Trump is in a unique position for a non-incumbent presidential candidate. He has a record as the nation’s chief executive. And to win, he needs to shape how millions of voters remember that time. Whether he realizes it or not, the human mind affords him much opportunity. How we recall the past, Hirst says, “is a real memory hole, and it can become so deep it’s difficult to get out of…It’s not a pleasant story, but it’s what we are as humans.”

Dehner wonders if accurate memories might end up prevailing in this election, but he is not sure: “In the quiet of the voting booth or just in thinking about it, will voters revisit what it was really like during the previous administration? These personal memories remain, and I suspect there will be a certain unease about how one portion of the candidate pool is seeking to portray that past. As an academic, I’m curious about how this all will turn out; as a citizen, I’m quite disturbed.”

Correction, September 18: An earlier version of this article misstated the study’s findings on preventable deaths.

Top image credits: Photo illustration by Alma Haser; Bill Pugliano/Getty; Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty; Kevin Dietsch/Getty (2); Anna Moneymaker/Getty; Rebecca Noble/Getty; Chip Somodevilla/Getty (2); Emily Elconin/Getty; Spencer Platt/Getty