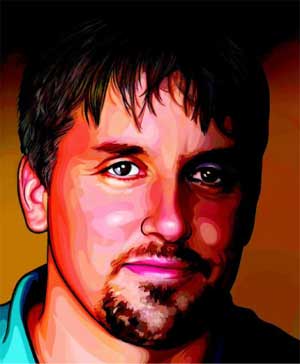

Photo: NEWSCOM/LILO/SIPA

Richard Linklater’s fictional adaptation of Fast Food Nation, Eric Schlosser’s Big Mac-is-murder exposé, starts with an alarmingly close shot of a fat-filled patty sizzling on a grill at “Mickey’s,” home of “the Big One.” Soon we learn that “there’s shit in the meat,” literally: Seems the “gut table” at the meatpacking plant is making for some especially unhappy meals.

Crappy beef is only one of the subjects of Fast Food Nation, which zooms out from the burger to reveal its origins. Working from the screenplay he cowrote with Schlosser, Linklater wanders, somewhat in the roving style of his debut feature, Slacker, among three loosely connected stories. There’s Don (Greg Kinnear), a burned-out Mickey’s marketing executive who’s ordered to get to the bottom of the company’s fecal matter; Amber (Ashley Johnson), a young Mickey’s employee who gets a whiff of what she’s cooking and considers taking action; and Sylvia (Catalina Sandino Moreno), an undocumented worker at the plant who snuck across the border from Mexico to a job in which she’s essentially treated like meat.

Linklater, following his rotoscoped head trip A Scanner Darkly, has made his second film this year about the culture of addiction and exploitation. As a measure of the director’s rare hunger for realism in the commercial realm, Fast Food Nation is a whopper.

Note: This is an extended version of the interview that appears in the November/December 2006 issue of Mother Jones magazine.

Mother Jones: You’re a prolific filmmaker who chooses from a wide variety of projects. Can you describe the motivation for making this particular project at this time—and in this particular way?

Richard Linklater: It’s never a fully conscious choice; it’s just something that kind of comes over you and kind of compels you. I like the book a lot and met Eric Schlosser when he came to town—here to Austin, where I live. And we got to talking about it as a potential movie and it just went from there. I guess my personal interest in the subject matter goes back a long way on all levels. I’ve been trying to make a movie for years about industrial workers. I wrote a script a script about a guy working on the automobile assembly line; I never could get money for that. I did a pilot about minimum wage workers for HBO that didn’t get picked up; they thought it was depressing, even though it was a comedy. I’ve always been interested the industrialization of our food; it’s been an issue for me from an environmental and animal rights and human health perspective. Fast Food Nation for me was an opportunity for me to delve into a lot of things that I felt connected to. For one thing, I saw the movie as a way to depict these workers—looking at the issues through these people’s lives. In a way, I’ve been trying to make this movie for years; Fast Food Nation provided the perfect jumping-off point.

MJ: The film is fiction, of course. Did you ever think of making it as a documentary?

RL: That would have been redundant. The book is a brilliant piece of nonfiction. Also, in directing, you have to find your way to the subject. For me, the movie represents myself at different phases of my life. In my early 20s I was an offshore oil worker for about two and a half years; I always wanted to depict an industry as seen from the bottom, looking up. So it was easy to make that jump to the boots-and-hard-hat world of the meat-processing plant. Then there’s the powerless student figuring out what’s appropriate when you think something’s not right. And then there’s Don, who finds out something’s wrong and chooses not to pursue it too much, accepts the status quo, and walks out of our movie altogether. He’s kind of myself, too—or all of us, when you’re not actively combating what you know is wrong. . It brings up the question: What do you do? You can vote with your consumer dollars, you can vote in elections—supposedly. But is that enough? What should you be doing? What’s the proper response. I mean, he’s not a bad guy. He assimilates information and moves on; he tucks it away and says, Well, I guess that’s the way it is, I don’t want to threaten my position in this world. That kind of complacency is so prevalent that it’s not even like writing a character.

MJ: It’s rare for an American movie to tell a story that’s the rule rather than the exception. Usually it’s the Remarkable Story of a Guy Who Bucked the Odds in Pursuit of Truth and Justice.

RL: Eric and I were pretty adamant about saying no to that. Don is no Erin Brockovich. The film pushes responsibility back on the audience.

MJ: No shortages of risks, are there, with that kind of approach—particularly in a commercial medium, right? You have a movie that doesn’t deliver.

RL:I’m not gonna say that it was easy to get this film made and to keep some of those subversive elements alive. You hope it’s appreciated and not just frustrating to a viewer who has been so conditioned to expect something in particular. But I was more interested in the question of how to tell a story. To me one of the most interesting aspects of the movie is that you have a lead character who literally leaves the movie halfway through—because he doesn’t come through on his lead character status. He sort of doesn’t qualify, he doesn’t earn the right to remain around. In a way he chooses not to be in the movie. He’s replaced by Amber, with her growing awareness. I don’t know if cynicism is the word for what he’s got, but his complexity is replaced by Amber’s budding awareness and activism—a switch-off occurs there.

MJ: That switch corresponds to the film’s desire to reach a younger audience—which in turn corresponds to Eric Schlosser’s own direction of late, publishing a Fast Food Nation book for kids, Chew on This. Do you think that young people have a chance to make a change?

RL: Well, we hope, you know? That’s the age that people are most receptive to putting yourself on the line and believing in change and everything. It depends on your background; maybe your awareness comes at the end of high school or in college, somewhere around there. For a lot of us, awareness is merely realizing the extent to which we’ve been lied to all our lives. You start educating yourself, you become motivated, you follow your muse where it takes you. And you see the world in a different way, you start making decisions based on what you feel is right. That’s how it happened for me. I grew up in a little town in east Texas, where it was really not on the table to question certain things like whether you should eat meat or not. In health class they’d describe a hamburger, fries, and a shake as a well-balanced meal: All the food groups are represented—you’ve got vegetables on the hamburger, you know, the lettuce and tomato, you’ve got meat, so that’s your protein, you’ve got bread, the bun, and you’ve got dairy, the shake. So you’re all good to go. So it wasn’t until I got a little older that I started to say, “Hmmm.” The more I studied that industry, the more I said, you know, I’m not going to support that—industrial chicken farming and pig farming, it all seems so ugly and bad all around. It can be hard for a young person in certain environments to know that it’s even an option to disapprove.

MJ: Amber has some privileges.

RL:Yes, and at the same time it’s hard for a 50-year-old who has been living a certain way to make a change; it would almost be for him to admit that he’s been wrong for the last 30 years. I see the world as an amalgamation of information and awareness; I’m very reliant on investigative journalists and writers and people out there sharing their information, sharing what they know about the policies of industries and what’s behind those policies. You have to have your feelers out there and you can’t attack the person that’s giving you the bad news; you have to be able to say, I’m not shopping there, I’m not buying that.

MJ: What kind of research did you do to prepare for the movie?

RL: I met a lot of ranchers; I went to slaughterhouses; I met workers in Mexico. It was an eye-opening experience for all of us on the movie. That’s why you do it: the personal journey. I saw the plight of many ranchers: how they’re being squeezed, how industrialization is just eating them.

MJ:What were some of the challenges of making the movie, knowing that the fast food industry had you on its radar?

RL:Well, it’s funny how McDonald’s is like the insecure teenager: They assume the movie is all about them. We were pretty much an underground production, trying to be as low-key as possible to get access. I’ve never made a movie where from the outset we were a target, because of the impact of the book and the enemies it made. It’s amazing what you can get away with in this culture. But when you threaten a huge, powerful corporation, then, man, they really pay attention. I heard that some people who let us film in their businesses are in trouble with their corporate elders.

MJ: Are you seeing a campaign developing against the film?

RL: Yes, but they got outed. McDonald’s leaked its countercampaign last spring. There was a big Wall Street Journal article about it. We all laughed; it was funny how seriously it was taking us. It smartly pulled back, said it wasn’t doing anything. It’s clever about never taking you straight on. It pays shadow organizations to do its dirty work.

MJ: Do you see a certain “Swift Boating” of muckrakers happening?

RL: Believe it or not, McDonald’s worked with the same people behind Swift Boat.

MJ: The DCI Group? The same people behind that YouTube spoof of An Inconvenient Truth?

RL: Yes. Eric was confronted by them at readings; they were handing out flyers accusing him of telling lies. They make it seem like some citizens’ protest. When you talk to them, you find out that they’re on the payroll—10 bucks an hour to hand out flyers. That’s how it works: You announce yourself as being one of two sides, and the media portrays it as a debate. Maybe there’s global warming and maybe there’s not! Maybe there’s evolution, maybe there’s creationism! Everyone can just believe what they want to believe.

MJ: How do you see your work responding to the new political realities of the world?

RL: I don’t think I’ve changed; it’s more that the culture is allowing the movies I want to make to get green-lit. I’m trying to get one made that deals with the Iraq war. It’s about three old guys, one of whom has lost a kid in the war. It’s the war as seen through the eyes of a grieving parent. I’ll always be interested in depicting life from more of a working-class angle.

MJ: Which is rare in American movies.

RL: It’s not that uncommon. People give Hollywood crap for being full of “outspoken liberals,” blah blah blah. But the entertainment industry is one of the only industries where you have people—actors and musicians—who have a voice but don’t have privileged backgrounds, or college degrees.

MJ: The characters are so disparate—separated by circumstance and class and race and geography. You have the sense that if they could get together in some way, if they could join forces, then they could reach a solution. It feels like the film is as much about the effects of isolationism as it is about anything else.

RL: Yeah. It’s a depiction of a divided and conquered kind of world, with people who don’t communicate or cross paths much. Everyone is in their own somewhat comfortable bubble—even the undocumented workers sort of find their own niche, they’re separated at the plant, their apartment complex is probably 95 percent poverty, undocumented workers.

MJ: There’s so many causes of isolationism in America. But how do you measure it? Your two films this year are so sad. I mean that as the highest compliment.

RL: Thanks, yeah. It’s a real question. I mean, A Scanner Darkly is the sadness of the alienated individual within the larger culture that’s kind of clamping down and Fast Food Nation is more of the systemic sadness—the idea that we’re all cogs in a machine that’s so much bigger than all of us, that one person can really have no effect whatsoever. The Kinnear character comes to that realization: I can do this or that, but so what? They’ll just get rid of me and find someone else. The system seems big and insurmountable, especially when coupled with the level of comfort that so many Americans enjoy. Even some of our poorest people, those without insurance, still have iPods and cable TV. There’s a high level of consumer goods around; people are kept from feeling desperately poor even if they are.

MJ: I love that line in Fast Food Nation about how the cows don’t leave the fence because they like their genetically engineered food so much better than real grass. That’s why we stay: We’re placated.

RL: It tastes better, yeah. Things are kind of okay.

MJ: Stepping through this logically and philosophically, then, does that say to you that things have to get worse for people in order for things to get better? That hope lies in some kind of catastrophe?

RL: I thought that for so long, but then it does get worse. Abu Ghraib. This ridiculous, horrific war in Iraq. Katrina. I mean, short of something happening directly on our shores, where tens of thousands of Americans were dying every week or something, I don’t know what it would take. Things have gotten worse and they haven’t gotten better yet. I don’t know what the next move is. Part of me is optimistic that people, whether they like it or not, are being kind of awakened. They realize that the world the United States is occupying is not the same world that we were in even 10 years ago. Everything is different. Maybe there’s more of a discontent and cynicism toward our current administration, but I don’t know. What would be an example of it getting worse? An economic collapse of some kind, maybe, a situation where everyone is scrambling, that would be worse. But then what? That would just mean that we’d switch regimes. All you can do is just vote in someone new. If “It’s the Economy, Stupid,” then you’re just switching business partners. It’s hard to imagine any true alternatives. I mean, the hope for so many people is the emergence of a really viable third party, one that represents 90 percent of the population and the issues that those people care about: healthcare, retirement, education, pensions. There’s so many things that we could all agree on outside of divisive issues. You’d think that if some force arose that was really speaking to those issues, then it could happen. But I don’t know what it’ll take. Things seem primed right now in some ways; if some charismatic person stepped up, someone who was against this current war and was in favor of things that people care about. But I don’t know if the Democrats can deliver even a hint of that.

MJ: One more line from the film that I love: It’s when the kid says, “The most patriotic thing I can think of doing right now is to defy the Patriot Act.”

RL: It got a round of applause in Cannes! But you know, when we screened the film down in Orange County, it kind of got a chill. [Laughs.]

MJ: That’s a backhanded compliment.

RL: Well, it’s funny because the line isn’t necessarily the movie talking—it’s just something that a hyped-up college kid would say.

MJ: Do you hope the film will change people’s eating habits? Did it change yours?

RL: My eating habits were already set. You think you know about fast food—I mean, I knew it wasn’t, like, one cow, one hamburger—but when you see everything that goes into it, it’s shocking. The meat on the conveyor belt goes into a big vat along with a bunch of this white stuff. I asked, “What’s that?” They said, “Oh, that’s fat, to give it that sizzling quality.” And they add beef hearts to give it color. I put that in the movie. Once you see what goes into your burger, why not choose a healthy alternative, like a veggie burger?

MJ: Do you advocate vegetarianism?

RL: I don’t know. Eric is not a vegetarian. I am. But we both agree that if you eat meat, you should know where it comes from and support the people who are doing it right. Get a good cut of meat from a free-range, nonexploitative, nonindustrial ranch. We have this image of a healthy family farm with some pigs and a cow and all these different crops. Puncture that myth and you realize that it’s an industrial farm where there’s only corn or only lettuce and it’s sprayed with pesticides, and all these pigs live in this tiny space, never get to touch the ground, eat crap all day, and they can’t even turn around. Every person has to understand that.

MJ: And the film will help that?

RL: I don’t have any delusions that the movie is gonna change much. [Laughs.] Yet at the one U.S. screening we had, a lady came up and said, “I can’t eat this stuff and not think about everything that’s behind it—the workers and the whole system.” So that’s a good start. I want to know what’s behind everything I’m asked to buy—whether it’s my food or my government’s policy on another country. I have the right to know the real cost.