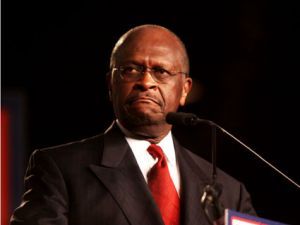

GOP presidential candidate Herman Cain is refusing to disclose the names of his top policy advisers.<a href=" http://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/6183942539/sizes/l/in/photostream/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

According to the latest poll, if not necessarily the conventional wisdom, Atlanta businessman Herman Cain is currently the frontrunner for the GOP presidential nomination. The natural consequence is that people now care about the actual ideas he has proposed, and the results aren’t pretty: Independent analyses of Cain’s signature 9-9-9 tax plan show that it would double taxes on the middle class, and hike taxes on low-income Americans by a factor of nine. That’s less surprising when you consider that the plan was crafted not by a professional economist or budget wonk, but by Rich Lowrie, a financial manager at a Wells Fargo office in Pepper Pike, Ohio, with a B.S. in accounting.

So how has Cain responded to the scrutiny? By clamming up. CNN’s Kevin Liptak reports that Cain is now refusing to name any of his other economic advisers, because he’s concerned that they will become punching bags for his opponents:

“They often ask me, ‘Well, who are your economic advisers?'” Cain said in Bartlett, Tennessee. “And they hate it when I say, ‘I’m not going to tell you.'”

Cain continued, “I’m not going to tell you! They’re my advisers, not yours. They just want to know who my smart people are so they can attack them.”

Cain said the media was criticizing his 9-9-9 tax plan, which proposes levying a 9% tax on income, corporate profits, and national sales, because they weren’t accustomed to such sweeping change.

Incidentally, I’ve already sent in a request to the Cain campaign to see who is advising the candidate on foreign policy, but have not heard back on that, either. That’s relevant because Cain, by his own admission, does not know very much about the topic. He recently called the Uzbekistan “Ubeki-beki-beki-stan-stan,” and said he didn’t care about such “small, insignificant states around the world” despite the fact that it borders Afghanistan, where the United States has been at war for over a decade. (Relatedly, he refused to offer any sort of opinion on the Afghan war, saying he hadn’t thought about it enough.) Last spring, Cain professed not to understand the concept of “right of return,” despite making support for Israel the centerpiece of his foreign policy agenda. To all of these concerns, Cain’s response has consistently been that his ignorance was irrelevant, because he would consult with his advisers before making any sort of major policy decision.

Normally, candidates openly tout the names of their high-profile advisers (see Mitt Romney, for example). Given his total inexperience in national politics, Cain’s code of silence on his kitchen cabinet is hard to figure.