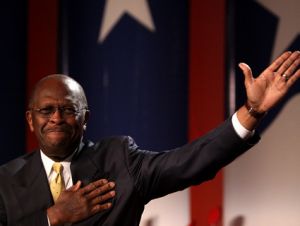

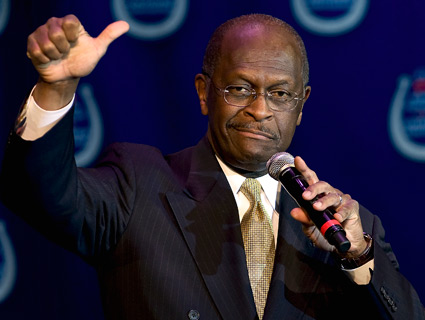

2012 GOP presidential candidate Herman Cain.Brian Cahn/ZUMA Press

GOP presidential candidate Herman Cain has emphatically denied that he ever sexually harassed anyone. He says that he was falsely accused by the women referred to in the blockbuster Politico story Sunday alleging that he had made inappropriate sexual advances and engaged in other unseemly behavior towards women while serving as head of the National Restaurant Association (NRA).

Cain may think this line of attack is a sensible media defense strategy, given that the settlement agreements between the women who said he harassed them and the NRA are confidential. But according to at least one prominent employment lawyer, calling his accusers fabricators could open Cain up to a defamation lawsuit, especially if it turns out their allegations have substance. Debra Katz, a DC employment lawyer who frequently represents plaintiffs in sexual harassment cases, says that if she were advising those women, she might suggest a counter-offensive. “These women have potentially got a claim against him. That’s potentially defamatory,” she says of Cain’s comments.

Katz notes that no one knows what the actual allegations are against Cain, so it’s hard for the public to really know what happened. But Katz says Cain’s media strategy has the potential to backfire on him. “Herman can continue talking,” she says, but “he’s going to get himself in trouble in this.”

If Cain was really falsely accused, Katz notes, there is one way that he could clear the air about the allegations: make the settlement agreements public. The NRA reportedly paid off at least two women who complained about Cain’s behavior, and in exchange, the women signed confidentiality agreements promising not to talk about their allegations publicly and left the organization. The details of many of their charges, as well as the amounts they were paid, have not been made public. At the National Press Club Monday, Cain reiterated that his former employer has a policy against releasing personnel information, so it can’t produce the documents that might back him up.

The settlement agreement makes it difficult for the women themselves to speak publicly or to instigate a change to the terms of the settlement agreement, which may carry serious financial penalties for breaching it. But Katz says that there’s not much stopping the NRA from doing so, despite what Cain says. In fact, she says, NRA could also disclose many details about the allegations the women made, without revealing their names, without even violating the agreement. Cain probably just needs to ask them to do it.

“There are many way they can legally find ways to disclose the information without violating the agreement,” she notes. Not releasing the details, she says, is simply “a convenient way to duck the allegations.”