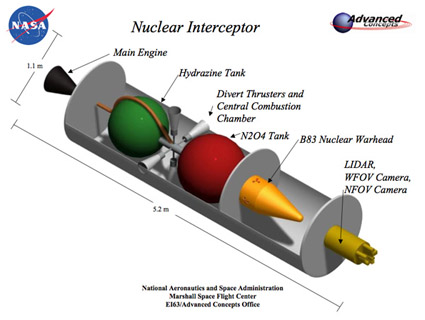

Cutaway of a proposed "nuclear interceptor" for deflecting a planet-killing asteroid.NASA

David Dearborn is one of a small handful of people who can say they’ve designed their own atomic bomb, lowered it into the Nevada desert, and watched it detonate, instantly vaporizing the earth around it and swallowing the desert floor in an immense gas-filled crater. Through the final decade of the Cold War, Dearborn, a physicist at California’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, was among perhaps the top 10 scientists in the United States’ atomic research complex. Four times he saw his creations explode before his eyes, witnessing the massive power of a weapon designed to be so destructive that its keepers would be loath to ever use it.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the gradual dismantlement of American and Russian arsenals, there would seem to be little use for real-life Dr. Strangeloves. Yet far from suffering obsolescence, the 62-year-old Dearborn and his colleagues in the nation’s nuclear weapons laboratories are still busy tinkering with and coming up with new uses for our atomic weaponry. In fact, the Livermore lab has seen its research budget expand 50 percent since 1994, to nearly $1.5 billion. President Obama’s 2012 budget requested $11.8 billion, a 5 percent boost, for the National Nuclear Security Administration, the Department of Energy office that oversees nuclear weapons R&D and maintains our stockpile of more than 5,100 active warheads. Nearly half the NNSA’s budget is spent on what Rep. Mike Turner (R-Ohio), chairman of the House Armed Services Strategic Forces Subcommittee, has enthusiastically described (PDF) as “providing meaningful work to our talented scientists and engineers”—such as Dearborn.

What exactly is that meaningful work? Even though new warheads aren’t being built and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty prohibits atomic testing, “modernization” efforts are endowing existing weapons with new capabilities. Warheads are getting “life extension” upgrades such as a “dial-a-yield” option that adjusts their explosive power; “dumb” gravity bombs are being modified so they can act as “robust nuclear earth penetrators,” or nuclear bunker busters.

Dearborn insists that most of the recent modifications have safety at heart. “Earlier, it was about reducing size and weight or getting more bang,” he says, but now “it’s about higher safety, designing things that you could machine-gun and hammer and they would not go off.” As long as the United States has some kind of nuclear stockpile, he says, “You ought to know that it works.”

His work has been focused on new uses for existing nuclear technology. The one he’s most passionate about is a peaceful application: using nuclear bombs to protect the planet from “Earth killer” space objects. Dearborn’s evangelism has convinced several important supporters that “the nuclear option is the only useful technology for large asteroids.” A 2007 NASA study (PDF) concluded that atomic explosions “are the technology of choice for deflecting” objects near Earth. Rep. Dana Rohrabacher (R-Calif.), who sits on the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, has made asteroid-killing nukes a personal cause. “We should be able to spend hundreds of millions of dollars in order to protect us from an asteroid or a comet that would do far more damage than the terrorists could ever imagine,” he explained in a hearing that trumpeted NASA’s (and Dearborn’s) findings.

David Dearborn Lawrence Livermore National LaboratoryDearborn launched his anti-asteroid crusade on his own. For several years, he paid his own way to present his views at scientific conferences. “The lab has always encouraged scientists to become involved in research that’s outside of the narrowest programmatic views,” he says. Only after the astronomy community took note did his bosses say, “Hey, maybe we should be funding this.” Teams of researchers are now working on the problem at Livermore and Los Alamos, its sister lab in New Mexico. Nobody’s better qualified to figure out how an atomic explosion would affect a space objects hurling toward Earth, Dearborn says. After all, “We have experience in making holes in the ground.” All the same, given the low short-term probability of an asteroid collision with Earth, he concedes, “Probably we shouldn’t drop everything and pour a whole lot of resources into it.”

David Dearborn Lawrence Livermore National LaboratoryDearborn launched his anti-asteroid crusade on his own. For several years, he paid his own way to present his views at scientific conferences. “The lab has always encouraged scientists to become involved in research that’s outside of the narrowest programmatic views,” he says. Only after the astronomy community took note did his bosses say, “Hey, maybe we should be funding this.” Teams of researchers are now working on the problem at Livermore and Los Alamos, its sister lab in New Mexico. Nobody’s better qualified to figure out how an atomic explosion would affect a space objects hurling toward Earth, Dearborn says. After all, “We have experience in making holes in the ground.” All the same, given the low short-term probability of an asteroid collision with Earth, he concedes, “Probably we shouldn’t drop everything and pour a whole lot of resources into it.”

Government scientists have been dreaming up unusual applications for nuclear weapons technology ever since the dawn of the Atomic Age. The ’50s brought us Atomic Annie, the Army’s nuclear field cannon, and the Davy Crockett, a one-man field rocket tipped by a 50-pound warhead that could level two city blocks. There was Operation Plowshare, which envisioned using nukes for civil engineering, from widening the Panama Canal to extracting natural gas. NASA flirted with Project Orion, an ambitious plan to launch a spaceship into interplanetary orbit with 800 atomic explosions.

Critics of the nuclear weapons complex see the ongoing search for new ways to use nukes as wasteful, at best. Little new research on atomic weapons is necessary, says Robert Civiak, a weapons budget analyst who worked as a physicist at the Livermore lab in the ’80s. Gauging the behavior and reliability of a nuclear blast is “a mature science we’ve had for 70 years,” he says. Many anti-nuclear activists suspect this is more about money than science or national security. The nation’s three main nuclear labs “are accustomed to the style in which they were born,” says Jay Coghlan, the director of Nuclear Watch New Mexico, a clearinghouse for open-source information on the labs. “Large and lavish.”

While Dearborn has been promoting nuclear weapons as a sci-fi savior, he’s also been working on a new military applications for Cold War-era weaponry. The Prompt Global Strike system was conceived by the Pentagon under Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld to solve a post-9/11 problem: What if the United States had the need to immediately and stealthily strike a target halfway around the world, beyond the range of bombers, drones, or Seal Team Six? The goal, Dearborn says, was to develop something to address “situations when it’s ‘Oh my God, we’ve got to do something and we’ve got to do it in the next few hours!'” In other words, the Osama bin Laden problem on steroids.

A Hypersonic Technology Vehicle launched from a modified ICBM Defense Advanced Research Projects AgencyThe military already had a weapon designed to solve the time-sensitive delivery problem: intercontinental ballistic missiles. Of course, dropping nukes on terrorist camps is a no-go. But if atomic warheads were swapped out for conventional explosives, the Air Force stated in its 2003 transformation plan (PDF), ICBMs could accomplish the aim “of holding terrorist-related targets at risk everywhere. It would also allow the US to project power almost immediately in areas with no forward-deployed forces or easy access.” In 2006, the Bush administration pledged $1 billion to put two conventional ballistic missiles on each of its nuclear-launch submarines.

A Hypersonic Technology Vehicle launched from a modified ICBM Defense Advanced Research Projects AgencyThe military already had a weapon designed to solve the time-sensitive delivery problem: intercontinental ballistic missiles. Of course, dropping nukes on terrorist camps is a no-go. But if atomic warheads were swapped out for conventional explosives, the Air Force stated in its 2003 transformation plan (PDF), ICBMs could accomplish the aim “of holding terrorist-related targets at risk everywhere. It would also allow the US to project power almost immediately in areas with no forward-deployed forces or easy access.” In 2006, the Bush administration pledged $1 billion to put two conventional ballistic missiles on each of its nuclear-launch submarines.

Dearborn and his colleagues got to work making ICBMs accurate enough to pinpoint targets with non-nuclear payloads. That was never a concern when the missiles were nuclear-tipped. “When throwing nuclear warheads, it’s a lot like horseshoes, in that closeness counts,” he says. “The accuracy is not necessarily what you need for a conventional weapon.”

The ICBM plan has well-placed champions. In 2008, University of Maryland public-policy professor Steve Fetter extolled its virtues in a lecture at Princeton University. Ballistic missiles are cheap, plentiful, and the only PGS technology available in the short term, he explained. He shrugged off the possibility that the Russians might mistakenly think an ICBM was part of a nuclear attack. They would quickly realize that they weren’t the target, Fetter stated; and if they mistakenly assumed they were the target, his PowerPoint notes stated, “Russia would not retaliate to launch of 2-4 missiles.” In 2009, Fetter went on leave from Maryland to become assistant director of the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy. (He declined to talk on the record.)

The Obama administration has continued funding for Prompt Global Strike, but it is now focusing on delivering explosives via a hypersonic aircraft just outside the Earth’s atmosphere. Dearborn’s been a part of that effort, too. Earlier this year he participated in test shoots of modified Peacekeeper missiles, which then launched a vehicle that streaked over the Pacific Ocean at 20 times the speed of sound.

Like most of the nation’s nuclear weapons designers, Dearborn is ready to change gears once again if necessary. Though he respects calls to reduce the size of our nuclear stockpile, he confesses that he still occasionally pines for the old nuclear age. “I was one of the people that was involved each year in saying, ‘What is there that’s interesting and we haven’t done yet in nuclear testing?’ And that,” he laughs, “was an interesting time.”