<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-87322042/stock-photo-cayman-brac-quiet.html?src=csl_recent_image-1">lweissman</a>/Shutterstock

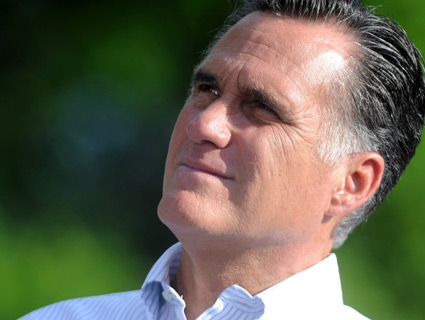

Mitt Romney’s taxes are once again in the news thanks to Friday’s release of his full 2011 tax return. As with his 2010 filings, the documents highlight the GOP candidate’s extensive overseas holdings, which some tax experts believe has allowed him to lessen his tax liability. But the problem with Romney’s reliance on offshore tax havens goes beyond his own tax bill.

The Internal Revenue Service and many members of Congress have sought for years to close some of the loopholes that are draining billions of dollars from the federal treasury and shifting the tax burden from wealthy corporations to average individuals. Yet through his work at Bain Capital and his personal investments, Romney has supported a shadowy financial system with far-reaching ramifications for the US and foreign governments.

To date, Romney has refused to answer questions about why, for instance, he needs to keep some of his money in places like Bermuda, rather than a bank in Belmont, Massachusetts, or in a US-based investment vehicle. When he dodges these types of questions, Romney’s not just depriving voters of critical information about his own taxes. He’s sidestepping a much larger policy question about this unaccountable financial system that has been a key driver of global inequality.

Offshore tax havens are better known for facilitating money laundering and tax evasion than legitimate business. They are jurisdictions that generally offer extremely low tax rates to foreign investors (zero in the case of the Cayman Islands). They also offer sanctuary to people or entities looking to avoid other rules and regulations or seeking to shield their assets from lawsuits in their home countries. And, of course, tax havens provide secrecy. They hide owners, partners, and investors from tax authorities or jilted spouses and often refuse to comply with criminal investigations by other countries, which is one reason they’re popular with both drug kingpins and Americans tax evaders.

Romney has investments in a number of well known tax havens, including Ireland, Luxembourg, the Cayman Islands, and Bermuda. Until 2010, he held a few million in the Swiss bank UBS, which in 2009 was forced to pay the US $780 million in fines and penalties for helping more than 17,000 Americans commit tax fraud by hiding as much as $20 billion overseas. The total value of Romney’s offshore investments is unknown, but his tax returns have revealed that he has at least $30 million invested in the Cayman Islands, in at least 12 different Bain Capital funds. When pressed about the relationship between his offshore investments and his low tax rate (he paid 14.1 percent on $13 million in income, according to his 2011 tax return), Romney has largely declined to answer questions about his overseas holdings other than to say, “I pay all the taxes that are legally required, not a dollar more.” Romney has also denied getting tax benefits from his offshore accounts. He told Fox News, “[T]here was no reduction, not one dollar reduction in taxes by virtue of having an account in Switzerland or a Cayman Islands investment. The dollars of taxes remained exactly the same. There was no tax savings at all.”

Similarly, a Romney campaign spokeswoman told Mother Jones that Romney’s foreign investments “are taxed in the very same way they would be if the shares were held in the US rather than through a Cayman fund. No taxes are avoided or reduced. These funds are registered with the IRS and report all income to investors and the IRS, just like domestic funds.”

Romney’s assertion that his offshore investments have not reduced his tax bill has been met with skepticism by tax experts. But assuming he’s telling the truth, his involvement in the offshore system and that of the company he started, Bain Capital, is still no less significant. That’s because while Romney may have done everything by the book with his offshore accounts, Bain’s other offshore investors may not have.

Bain’s has had investment funds located in the Cayman Islands since at least the 1990s, when Romney was still in charge. And the company has made clear that many of its funds there are designed to avoid US taxes. According to documents released by Gawker in August, one fund in which Romney still has money invested notes in a financial statement that it “intends to conduct its operations so it will…not be subject to United States federal income or withholding tax.”*

“The Cayman Islands jurisdiction for the Bain funds primarily makes it easy for their investors to cheat on their taxes,” says Rebecca Wilkins, the senior counsel for federal tax policy at the nonprofit Citizens for Tax Justice. “Because of that they can attract more investors and they can earn bigger management fees. “

Because of the secrecy laws in the Caymans and other offshore tax havens, Bain investors are hidden from tax authorities like the IRS. Unless they choose to report their holdings and income, as Romney has, there is no way for tax officials in the US or other countries to know that such holdings exist, much less find a way to tax them.

James Henry, a former chief economist at McKinsey & Co., describes offshore tax havens like the “bar scene in Star Wars.” He explains, “Dictators and kleptocrats used them to conceal stolen loot. Arms dealers and drug dealers use them to launder their deals. Google and Apple and Pfizer use them to park their intellectual property and pay themselves tax-free royalties. Banks use them to park lousy loans and stash the offshore accounts and assets under management of their wealthy individual clients, many of which are paying zero taxes back home…And so on.”

Some of those sorts of shady clients have been part of Romney’s portfolio at Bain. Nicholas Shaxson has written one of the most comprehensive stories about Romney’s offshore investments in a lengthy article in the August issue of Vanity Fair. It explored the nature of some of Romney’s early Bain investors. They included the late Czech-born British media tycoon Robert Maxwell, a fraudster and notorious tax evader who put $2 million into one of Romney’s first Bain funds, as well as a trio of anonymous corporations from another notorious tax haven, Panama. Other early investors, according to numerous news accounts, were members of the wealthy Salvadoran oligarchy with ties to right-wing death squads. Romney has credited Salvadoran investors for helping him get his company off the ground.

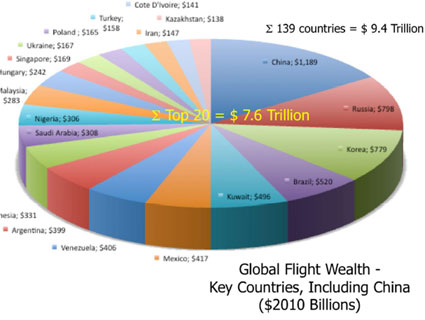

A significant amount of Romney’s personal wealth is sequestered in this deeply opaque financial system that not only caters to the global über-rich but also is a leading cause of global inequality. The amount of money siphoned out of the US alone via tax havens is staggering. American corporations now have an estimated $1.7 trillion in foreign profits stashed offshore and beyond the reach of the IRS, according to various government estimates. American multinational companies now keep at least 60 percent of their cash offshore to avoid paying US taxes, according to a recent Senate report. The Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations found that some companies, such as Hewlett-Packard and the pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson, keep almost all of their money offshore and rely on dubious methods to bring it back into the US without paying taxes. (HP, according to the committee, uses an endless series of short-term loans from its offshore accounts to its US parent, a move that has saved the company billions in taxes.)

Romney, who has decried the 47 percent of Americans who don’t pay income taxes, has nevertheless championed the use of tax havens by American big businesses. He told donors gathered at an August fundraiser that one reason big businesses were thriving today was because they know how to avoid US taxes by going offshore. “They know how to find ways to get through the tax code, save money by putting various things in the places where there are low tax havens around the world for their businesses,” he said.

Meanwhile, the negative impact of these practices on the United States and other countries is significant. In 2008, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations released a report estimating that offshore tax havens were costing the US at least $100 billion a year in lost tax revenue. “Tax havens are engaged in economic warfare against the United States, and the honest, hardworking American taxpayer is losing,” the committee’s chairman, Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.), declared when the report was released. “The iron ring of secrecy around tax haven banks and their deceptive banking practices enable and encourage tax cheats to hide assets from the United States.”

The use of offshore entities is one reason the US tax base has been shrinking dramatically over the past half century. In 1952, at its peak, corporate taxes were responsible for more than 30 percent of all federal tax revenue; today it makes up 9 percent. The burden of keeping government afloat, meanwhile, has fallen heavily on individual taxpayers as a result. In 1952, according to a report from the Congressional Research Service, the payroll tax accounted for only about 10 percent of federal revenue; today, it’s 40 percent.

Globally, the problem is even more severe. Just consider the case of tiny, impoverished El Salvador, whose wealthy oligarchs helped Romney launch Bain Capital. Between 2001 and 2008, the US government gave El Salvador more than $500 million in foreign aid. During that same time, more than a billion dollars a year disappeared from the country from illicit outflows, including those to tax havens, according to the Global Financial Integrity program at George Washington University.

The Tax Justice Network estimates that the global superrich have stashed between $21 to $32 trillion in offshore tax havens, a figure almost twice as large the GDP of the United States. The group estimates that if the income on these investments were taxed at 30 percent, it would generate as much as $280 billion in revenue annually. That’s more than double what the world’s developed countries collectively spend on foreign aid. The lost tax revenue would be enough to pull many developing countries out of debilitating debt and greatly improve the quality of life of their citizens.

“The system of offshore tax havens is one of the greatest threats to the global economy: undermining markets, helping shift gargantuan quantities of wealth upwards from poor to rich, then wrapping up much of it in secrecy,” says John Christensen, who served for 11 years as the economic adviser for the British tax haven of Jersey and now works for the Tax Justice Network in London. Before becoming a whistleblower, Christensen helped clients in South Africa evade anti-apartheid sanctions and to dodge taxes, among other things.

“The offshore system of secrecy jurisdictions is much bigger and many times badder than almost anyone realizes. To have a US president who is a serial user and abuser of offshore secrecy, and even a defender of secrecy jurisdictions, would pose frightening threats to the US and the global economy,” he adds.

While President Obama hasn’t been particularly successful in passing legislation in this area, he did outline a number of proposals to close loopholes in the US tax code that allow American companies to exploit offshore tax havens and avoid US taxes. Some of the measures would take aim at precisely the sorts of tricks Romney and Bain, and many others, have used.

Henry, the former McKinsey chief economist, notes that Romney’s involvement in offshore tax havens is no different from that of countless other high net worth individuals and investment firms. “It seems a little naive to denounce Romney for going along with a game that has become standard practice for every single firm in his industry,” he says. “This would be like singling out some individual plantation owner and condemning him for not converting all his slaves to hired workers in 1860.” The difference here, though, is that Romney isn’t just any mast of high finance. He’s asking Americans to put him in charge of the country. And as Henry says, if Romney is elected, “There is almost no chance that he would try to undermine this system.”

*Update: A spokesperson for Bain Capital said in an email that “the Cayman funds are partnerships, just like U.S. partnerships or S Corporations, and they pay no corporate taxes. Instead, partners pay 100 percent of their allocated taxes. Virtually all U.S. partnerships also do this. In other words there is no difference for a U.S. taxpayer between investing in a Bain Capital fund domiciled in the Cayman Islands and investing in a U.S. partnership.”