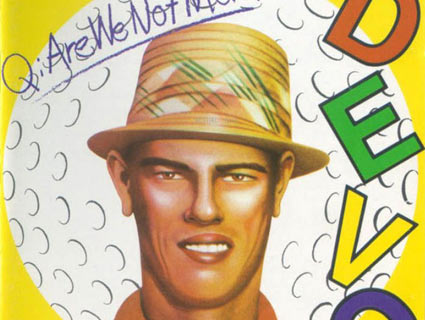

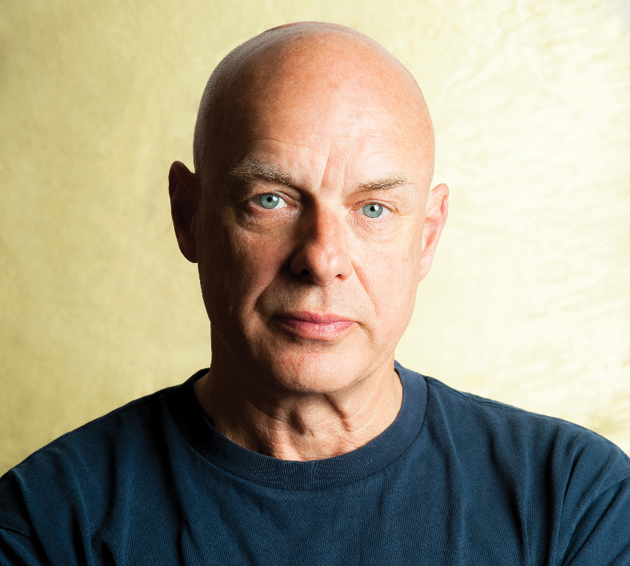

Even if you’ve never bought a Brian Eno album, you are probably familiar with the 64-year-old British composer’s work. A founding member of the group Roxy Music, he has produced albums by David Bowie, Coldplay, Devo, Paul Simon, U2, and the Talking Heads. He contributed to the soundtracks of The Lovely Bones and Dune. And remember that sound your computer used to make when you booted up Windows 95? He created that too.

Eno also makes his own music. After putting out four highly influential pop albums during the mid-1970s, he became intrigued by minimalist composers like Steve Reich and Terry Riley and began to think less about melody and more about texture. Eno called his experiments “ambient” music—works intended for a particular place or to set a particular mood—1978’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports was inspired by a gleaming new terminal in Cologne. He has also been a pioneer of “generative” music, wherein songs build and morph endlessly according to a set of rules determined by the composer.

LUX, out this week, is Eno’s 17th album and his first solo album in seven years. He is not calling LUX an ambient album, but it was commissioned for a specific place: the Great Gallery, a high-ceilinged hall in an 18th-century palace near Turin, Italy. I reached Eno by phone in London to talk about LUX, his “elaborate lifelong failure,” and how he accidentally re-created a Dolly Parton hit.

Mother Jones: The notion for Music For Airports struck you while you were at an airport. Does LUX have a similar sort of genesis story?

Brian Eno: This actually has two genesis stories. The first story was that I was commissioned to make a piece of music for a particular building in Turin that connects two palaces. It’s a long gallery—about 100 meters long, 15 meters high—designed in the 1740s by an architect called [Filippo] Juvarra. About a million visitors every year move through it; the people who run the place said they wanted to make them slow down a little bit because they felt that people were kind of racing from one palace to another and not noticing that they were moving through this beautiful space. So they said “Would you make a piece of music to slow people down?” basically. So I made a piece of music that I thought would work. And then I flew over to Turin with my piece of music—all the speakers and everything as I had specified were set up—and I put the piece on, and within 20 seconds I knew it was completely the wrong piece.

MJ: Why?

BE: It just didn’t connect with the place at all. First of all it sounded very modern, and the building doesn’t look like that. It’s an amazing piece of Baroque architecture. It’s full of details and, most importantly, it’s full of light. It’s got huge windows on both sides, so the main impression when you first walk in there is of light and the changing character of light during the day. And my piece had been made in my studio—it’s a nice piece, by the way, but very interior, very reflective, introspective; quite dark, I guess you’d say. I had my little portable studio with me, so I thought, okay, I’ll spend a couple days sitting here and I’ll try to find out what sorts of things are going to work. And by the time I left, I had a palate of sounds and the sort of feeling of pacing that was going to work, and then I came back to London and I made this piece. So the two stories are a) the invitation to make music for a particular space and b) the total failure.

MJ: Which one of those two pieces became LUX?

BE: The music that is being used in the palace became the basis for this album. I set up a thing in my studio where I had a very comfortable bed to lie on and I put speakers at each side of the pillow so I could lie down and be inside this piece of music. (I don’t like headphones.) And I did that because I wanted to adjust the music for the palace. While I was doing that, I was thinking, “I really love listening to this piece and, furthermore, it’s pretty different to any other piece that I’ve done.” I mean, I’m sure somebody that doesn’t know my work well would think, “Yeah that sounds like another piece of clinky-clonk Brian Eno music.” To me it’s different.

MJ: And your piece will run at the palace for five years, around the clock?

BE: No. Originally I thought it was going to be an around-the-clock idea and so I thought of making a generative piece, which is to say a piece that would keep remaking itself differently forever. But then I heard that actually what they wanted is to have an hour on, an hour off. In fact, I sort of suggested that as well, because I thought there are going to be people who come to this gallery who just want to be in the gallery without Mr. Eno putting his interpretation of the experience on it. And so I started to explore this idea of making the music episodic. And also something that you don’t have to listen to from beginning to end—you can enter at any point and leave at any point. So I started working with the idea of permutation, the ultimate something-for-nothing idea where you take a small number of elements and then you cluster them together in as many different ways as time and nature will permit.

MJ: Will you describe the elements?

BE: Very simple. The seven white notes on the piano—each section of the piece (there are 12 sections) is five of those seven white notes. If you calculate it, there are 21 groups of five notes in any group of seven notes. And although there are 12 sections, this piece actually uses nine of those groups because some of the sections repeat earlier ones. So that’s the formula. It’s very simple as a way of generating something. It’s my inner minimalist.

MJ: I attended your lecture in Asheville, North Carolina, and also went to see your generative visual piece, “77 Million Paintings.” What does it mean to have a piece of art that nobody can experience in full?

BE: Including its creator, actually, which is an interesting new idea. In that Asheville talk I was saying that we should think of composers nowadays as being more like gardeners than like architects. When you build a building, you finish a building. You don’t finish a garden; you start it, and then it carries on with its life. So my analogy was really to say that we composers or some of us should think of ourselves as people who start processes rather than finish them. And there might be surprises. I remember once in the early days of the piece of music that I used to use for my visual installations, we were working in the gallery setting up the show and the music was playing. And suddenly, completely unexpectedly, the first two bars of Dolly Parton’s “D-I-V-O-R-C-E” appeared—the precise melody! I was working there with a couple of people and we all suddenly stood up and looked at each other and just laughed.

MJ: Do you see a tension between producing pop albums and making your own generative music? Because those things seem diametrically opposed.

BE: They’re quite opposed, you’re right—but it doesn’t bother me. They are obviously not consistent at the level of form, but it seems to me there is consistency at other levels. For instance, I’m always fascinated to see whether, given the kind of fairly known and established form called popular music, whether there is some magic combination that nobody has hit upon before. And sometimes there is. I just heard a record last month by Port St. Willow—”Amawalk”—which I became completely entranced by. I just thought how amazing that somebody could take the same few chords, pretty much the same sorts of sounds—it’s quite hard to tell what is original about it, but I just know I’ve never heard it before. It’s such a fabulous record.

MJ: When you go into the studio with a band like Coldplay or U2, do you see yourself as doing fundamentally the same thing that you would be doing with a more countercultural band like the Talking Heads or DEVO?

BE: Yeah, I think so. First of all, it should be said that probably any of those bands would have been happy to sell out stadiums. I think most artists would be happy to have bigger audiences rather than smaller ones. It doesn’t mean that they are going to change their work in order necessarily to get it, but they’re happy if they do get it. Every band I’ve worked with also wants to be countercultural in the sense that they want to feel that they’ve gone somewhere that nobody else has been. I think that’s certainly the case with both Coldplay and U2. They’re both very committed to experiment; they’re both highly conscious of their audience as well, which is to say they don’t want to indulgently make things that would completely leave their audience behind. That’s not a sin either.

MJ: What about your audience? Do you just produce other artists whenever it seems like a good idea, or how do you balance all of that?

BE: Sometimes there are quite long periods when it doesn’t seem like a good idea—when I want to carry on with what I feel like doing. And it has to be said that producing is quite all-absorbing. It’s not something that you can sort of do in the days and then forget about. At night, you carry on thinking about what you’ve been doing during the day. So to produce somebody else, for me, is to say I’m giving up my work for a while. Now of course it’s in the nature of the way I produce things, I suppose, but I try to make it a kind of an extension of my own work. I try to make the music closer to what I want to hear. That sounds like a terrible thing to say, but I’m really not interested in what I think a lot of producers feel their job is, which is to say, “Well guys, what’s the music you want to make; I’m going to help you try to make it.” I’m more likely to say, “You know, I think music should be like this. This is what I’d like to hear, what do you think of that?” I’m not somebody who can just sit back and not interfere. I very much like interfering. [Laughs.] In fact, mostly when I’m producing now I play along with the bands. I’ve got my own equipment set up, and I join in and play and sometimes say, “I don’t think that chorus there works,” or “What about we make this change here?” But sometimes you walk in and somebody’s got a fantastic song; there’s no need to do anything except defend it, make sure it’s safely recorded.

MJ: What’s brewing in your immediate future?

BE: I don’t have any production things lined up. At the moment I’m feeling very happy doing my own exceedingly unpopular work. And I’d like to stick with that for a while. It must be quite mysterious to some people why I bother to carry on. Because, you know, I don’t sell that many records. They must think, “Why doesn’t he just work with bands who sell a lot of records?” The mysterious thing is that I somehow like this kind of elaborate lifelong failure that I’ve enjoyed. [Laughs.]

MJ: You were talking earlier about trying so hard to come up with a piece of music that fits this physical space. Yet a close adaption of that music is now being shipped out to people who can listen to it in any space they want—on a treadmill or in a basement or whatever. Doesn’t that sort of defeat the purpose?

BE: I’m quite prepared to let them decide about that. You know, I’m not sure everybody will agree on whether they think it’s a good idea to use it in different places. But first of all, I should say I make a lot of pieces of music that I never release as CDs. I have my computer—I was just looking yesterday—I’ve got, I think, 3,480 pieces of music that I’ve never released.

MJ: It seems that you focus on what interests you, and only then consider whether the world might be interested.

BE: Yes, though I also assume that there’s a very good chance that if I really like something, somebody else will as well. Because that has historically been the case even though I generally release things like little ships onto an ocean of indifference. Over time, people discover these little ships and say I really love that such and such.

MJ: There’s a sense in which a piece that’s meant to evoke a mood might be considered background music. Does that bother your composer ego?

BE: It doesn’t bother me at all actually, partly because I use music as background music a lot myself. For instance, there’s something I’ve been listening to for the last few days, which is made by those guys who used to be Stars of the Lid. It’s called A Winged Victory for the Sullen, made by Dustin O’Halloran and Adam Wiltzie, fabulous names. I don’t know whether they would be offended by the idea that I just put it on in the evenings when I’m in my studio working on visual things, which I like to do, but I absolutely love that record for allowing me to do that. I’m extremely grateful to records that allow themselves to be background material. And I often meet designers, graphic designers, or painters—writers as well—who say, “Oh I hope you don’t mind, but I always have your record playing when I’m trying to think.” And I think, “No I don’t mind at all. I’m really pleased that it’s of some use to you.”

MJ: I put LUX on while I was writing and while I was doing household chores, and I found that it didn’t compete for brain space in the way that a lot of other music would.

BE: Yes, and so a lot of composers would consider that terrible because they want their music to compete for brain space. I like the idea that it can exist as a sort of parallel part of your world. It can be a sort of aesthetic cushion, if you like.

MJ: In your early days, you were working with tape loops. How did digital technology change things for you?

BE: I love it. It was incredibly complicated doing long tape loops in the past. It was unbearable, to tell you the truth, and clumsy, and you know—I’m sure the photographs of it look fabulous and very romantic, but the reality of it was that it made it very difficult to do anything. It limited the number of experiments you could make, and you could only do it if you were quite well off and could afford a big studio. That doesn’t mean to say I only enjoy digital technology, I like a lot of things that came out of analog, but I don’t want to go back there.

MJ: What percentage of your music could be called “generative?”

BE: There’s rather a muddy middle ground of stuff that is partly generative and partly composed in the traditional way; LUX started out generatively but then I worked on it just as I would any piece of pop music. And even when I’m working on pop songs, I sometimes do a thing where I just put something random on the multi-track whatever it is—ProTools or whatever—an Arabic pop song or a recording of people on a street in Rome or something. And then at some point I will set up a mix and I’ll introduce that element and perhaps nothing happens—but at some point you might find, “Oh, listen to that; listen to what’s going on at that moment!” I don’t know whether that classifies as generative composing or not. Anyway, in pure terms, the purely generative is probably about 25 percent of what I do.

MJ: Do you think other people could improve their work by exploring these techniques?

BE: Um, I don’t know that I would recommend it to other people. [Laughs.] I think that because I’m interested, I make it work. Somebody said to me the other day, “It’s nothing to do with generative the fact that your record sounds nice, it’s because you’ve got good taste.” That might be true. I just have this complicated alibi about how I do it.

MJ: Yeah, could be.

BE: I have to finish now, I’m afraid.

MJ: Okay, well, thanks for your time.

BE: And could I just say thanks very much to Mother Jones for the Romney disclosures; I’ve always liked Mother Jones, actually, and now I read it quite regularly. That was a real coup, so well done.

MJ: Thanks. And thanks to Jimmy Carter’s grandson.

BE: I always liked Jimmy Carter as well. You know, when I lived in America first, which was in 1978, I was the only person I knew who liked Jimmy Carter. What really shocked me was not only that the Republicans hated him, which of course they would. But that the liberals hated him too, because they thought he was indecisive. And I thought, “You wankers, what do you expect?” You want liberals governing you, they’re going to be indecisive by definition. Liberals are people who aren’t certain. That’s what we like about them!