Former Sen. Russ Feingold (D-Wisc.).<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/jdlasica/6803903122/sizes/m/in/photostream/">jdlasica</a>/Flickr

President Obama’s decision to let his 2013 inauguration committee accept corporate cash and million-dollar donations marks quite a reversal for the president: for his first inaugural in 2009, he capped individual donations at $50,000 and banned corporate money. The Associated Press calls the decision “part of a continuing erosion of Obama’s pledge to keep donors and special interests at arm’s length of his presidency.” But for former Sen. Russ Feingold, it’s yet another sell-out by his friends in the Democratic Party to the big-money forces so dominant in politics today.

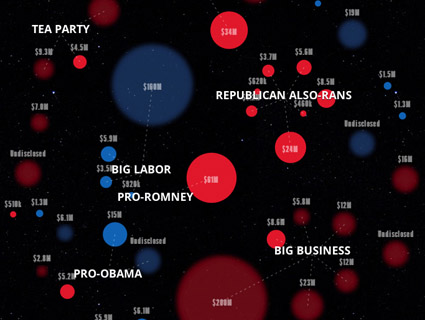

No Democrat has so publicly ripped his own party for embracing super-PACs and dark-money nonprofits than Feingold. In a new article for the journal Democracy, Feingold, who co-wrote the 2002 McCain-Feingold Act, the last major campaign finance restriction in the US, takes Democrats to the mat. He calls 2012 “a big step” back for Democratic-led efforts to get big money out of politics, and singles out Obama’s reversal on super-PACs. In February 2012, the president encouraged his donors to give to Priorities USA Action, the super-PAC backing him, while allowing his top deputies to appear at Priorities events. On the PBS NewsHour, top Obama strategist David Axelrod defended Obama by saying that the president hadn’t warned at all toward super-PACs but had to play by the rules of the game. You heard that a lot from Democrats in 2012. Yet with statements like that, Feingold says, Democrats were posing as a pro-reform party while tripping over themselves to “exploit any avenue to accept unlimited, corporate dollars to fund elections.”

Beltway Democrats, Feingold argues, aren’t going to reform big-money politics from the inside; they’re addicted and they just can’t quit. The task of fighting for real reforms to money in politics, of building what Feingold—who now runs his own pro-reform nonprofit, Progressives United—calls a “permanent majority” for reform, falls instead to liberal donors and activists outside of Washington.

Feingold says the most important thing big donors can do is stop giving—to super-PACs or any of the other Citizens United-enabled fixtures of our big-money politics. “Donors hold more leverage to create a movement for reform than almost any other actor in the political system,” he says. If donors ignore super-PACs and nonprofits, “Washington will notice.” And as for the liberal activists out there, they should redirect all the energy they’ve invested into passing a constitutional amendment reversing the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision and channel it into “achievable goals”—public financing of elections, disclosure of donors to dark-money nonprofits and shell corporations, overhauling the dysfunctional Federal Election Commission, the nation’s top elections cop.

The stakes are high, in Feingold’s view, for the Democrats. “Unless Democrats embrace election reform as a central tenet of our platform,” he writes, “we will face another era reminiscent of soft money—when the dominance of corporate interests meant that no matter what party held power, the influence of Big Money always won.”