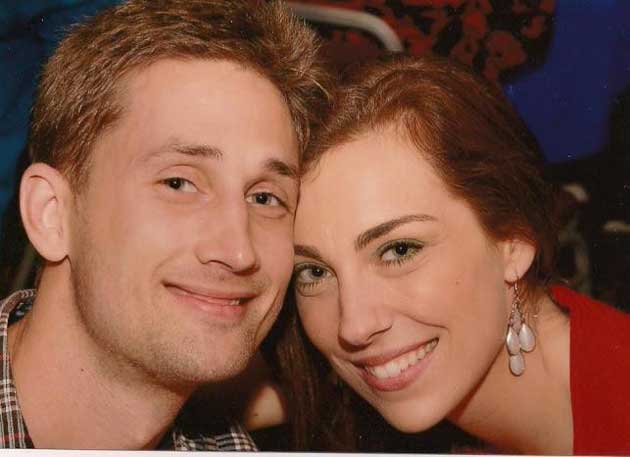

After Amanda Stevenson and her fiancé approached Anonymous, the authorities reopened her 12-year-old rape case.

A few weeks after Amanda Stevenson was allegedly drugged and gang-raped, the 14-year-old high school freshman packed a bag and fled her tiny hometown of Laurelville, Ohio, for a new life in suburban Virginia. But memories of that horrific night still haunt her, she says: the party in the hunting cabin deep in the woods. The locked room full of laughing young men. Trying to fight her way out of a fog of tranquilizer to say, “I feel strange” or “Take me home” or even simply “No.” Her naked body flopping like a rag doll as the teens passed her around and fondled her. Blacking out and awakening to find one guy after another climbing atop and penetrating her.

Despite the passing of years, Stevenson, now 26, says she still has trouble sleeping, still winces at any mention of the word “rape,” and still sometimes curls up in a corner, sobbing and angry. So one day this past January her fiancé, Tim Tolka, offered to help her go after the rapists, if that what she wanted.

She wasn’t sure it was. But then she read a story about a high school rape in Steubenville, Ohio, that had become national news thanks to the efforts of Anonymous, the hacker collective. “It was just so similar to what I had experienced,” Stevenson recalls. She decided then and there that her silence made her part of the problem.

The very next day, using a pseudonym, Tolka posted a plea on the Anonymous website AnonNews.org. “I have information about a second case of gang rape by local athletes in a small Ohio town that was squashed by the authorities,” he wrote. The couple went on to post the names, a phone number, and links to the Facebook pages of two of the men Stevenson said had raped her.

At first, not much came of it. Stevenson and Tolka, after all, were hardly the only ones looking to Anonymous for help. Following its success in bringing attention to the Steubenville case and a similar rape case in Nova Scotia, the group has been inundated with requests from dozens of self-proclaimed rape victims—far more than it can handle, members say.

The alleged ordeal began one night a dozen years ago, when Stevenson, then a freshman cheerleader, attended a basketball game. Classmates told her about a party happening afterward. Later that evening, she drove with her boyfriend to a remote hunting cabin. No adults were present, but there was plenty of loud music and booze. It was her first high school party, and she tried a sugary rum drink and her first hit of pot.

When her boyfriend was ready to leave, she arranged to get a ride home from someone else. She was having fun, even if the taste of alcohol wasn’t to her liking. Then someone handed her a Mountain Dew to sip, and that, she says, is when things got weird. Her arms and legs gradually began to go limp. She could feel her jaw and tongue slow down and she lost the ability to talk. From then on, her memories exist as vivid fragments.

The next thing she knew, a boy was helping her walk. She says he took her into a room occupied by at least five guys and locked the door. Her recollection then skips ahead to the part where her clothes were off, her head rolling limply as the boys passed her around, grabbing her breasts. Then everything went black—she thinks she is blocking out something horrible.

Next, she recalls being in a dark room with her clothes back on. In came a boy whose name and face she still remembers. He closed the door, took off her pants, draped her limp arms over his shoulders, and raped her. As he did so, she says, she stared at the ceiling. She couldn’t close her eyes, and still couldn’t move or talk.

Two more boys raped her in the same room that night, Stevenson would later tell local authorities. The first boy drove her home the next morning, quizzing her the whole way about how much she remembered.

At home, she told her parents what had happened. They took her to the local hospital, which gave her a rape test and contacted the Hocking County Sheriff’s Department on her behalf, records show. But she was too scared at the time to reveal the names of her alleged attackers.

Back at her school, a rumor started that the pretty freshman had made up a rape story to keep from being branded a slut. Four days after the sheriff’s department began interviewing students, someone threw a brick through the window of her family’s car, Stevenson told me. Eventually, she moved away, and the cops let her case go cold.

In January, when Stevenson and Tolka returned to Laurelville to pursue the case, they were dismayed to learn that the sheriff’s department had no evidence the rape ever had been reported or investigated. Deputies couldn’t find her case file, the clothes she’d worn that night, or the results of the rape test. “They never acknowledged that they had ever looked into it,” Stevenson says.

She spent the next few days hounding the department to find the records, which she hoped would lead them to reopen the case. Eventually she got tired of waiting, and the couple reached out to Anonymous a second time.

On January 20, they posted a plea for help on the private Facebook page of Operation Abuse Awareness, an Anonymous-affiliated Steubenville spinoff that claims to pursue bullies and sexual abusers. “This is a story that I don’t know how to tell,” her message began. “I am developing a migraine as I try to force myself to tell a story that I have tried to become so distant from the moment I woke up the next morning.”

Within a few hours, the couple found themselves in a lengthy internet chat with a young Anon who now goes by the screen name Jonathan Perez. Four days later, without telling them, Perez reposted their Facebook message on his public website, with the announcement: “This is sick, and we are going after them.”

The same day, Hocking County detective Caleb Moritz contacted Perez on Facebook. “We have heard from various sources that you, or someone you know, might have new information about Amanda Stevenson’s sexual assault,” Moritz wrote. “I would like to speak to you, or the person with the new information, so that we might further investigate the case and bring the perpetrator(s) to justice.”

Tolka and Stevenson were ecstatic, but they were taken off-guard by the news that Perez had posted her account of the evening, her post-rape hospital records, and the names and contact information of the alleged perpetrators where anyone could see them. “Dude, you’ve gotta take that story offline,” Tolka told Perez in a Facebook message. “[We] have thinking to do, and it is too early for this to be published in such a way.”

“lol, I can simply hide the page,” Perez wrote back. “I’ll do that now.” (He didn’t.)

About a week later, Moritz and another detective traveled to Virginia to interview Stevenson and let her know they’d reopened her case. (A spokesman for the sheriff’s department declined to comment on any aspect of the case).

Stevenson quickly discovered that getting the cops back on the trail was the easy part. But without the DNA evidence, prosecution would hinge on new witnesses coming forward—or a confession, which seemed unlikely in a 12-year-old case.

In March, the Anonymous subgroup AmeriSec held a rally for Stevenson on the steps of a local courthouse. “We feel the best way to help move her case into court is to get as many eyes on it as possible,” AmeriSec member Justin Fort, 23, told the Marietta Times.

The sheriff’s department disagreed. Moritz was particularly worried about Perez’s website. “If one of the three would happen to stumble onto that page and read the information contained on it,” Moritz told Stevenson via email, “they can use it to formulate a story and an alibi.”

Stevenson says she and Tolka again contacted Perez, who told them he couldn’t take the page down because he’d forgotten the password.

All in all, Anonymous has been helpful, Tokla says, but it hasn’t been a “silver bullet.” The couple had hoped the Anons might help them uncover new evidence, as they did in Steubenville and Nova Scotia. But when they attended a rally and met one of the leading Steubenville anti-rape organizers, known on Twitter as @Master_of_Ceremonies, he was reluctant to help. “I know personally I don’t really have time to jump into everybody’s thing that’s 10 years old,” MC told me. “There just aren’t enough people to do stuff all the time.”

Weeks passed, and Stevenson began to worry that the sheriff’s department was soft-pedaling its investigation. In late April, Tolka contacted the crime victims section of the Ohio Attorney General’s office, and requested that the state Bureau of Criminal Investigation get involved—it took over the investigation last month. On May 15, she met with Ohio Rep. Steve Stivers, whose office contacted me with a statement from the congressman: “Amanda is a very brave woman,” it began, “and I appreciated the opportunity to meet with her.”

In a brief interview last month, Hocking County Chief Deputy David Valkinburg urged me not to speak with the suspects for fear I would tip them off. He also suggested that Stevenson’s publicity efforts were counterproductive. “We don’t want to jeopardize an investigation, and we’ve tried to convince her of that,” he told me, “but she’s called some people before we even had a chance to interview any suspects.”

There’s also the issue of airing these types of accusations before anyone has been arrested or charged. One of Stevenson’s alleged attackers is listed on his Facebook page as being in a relationship, and he appears in a photo with a boy who could be his son. Another is shown with an older woman, perhaps his mother. Neither man responded to Facebook messages seeking comment. When I tried to telephone the man Stevenson said drove her home from the party all those years ago, the number listed on Perez’s website for him had been disconnected.

When I ask Stevenson why it took her so long to name her alleged attackers, she says she just hadn’t been equipped, as a 14-year-old, to confront reality. “You don’t want to accept that it happened, so it didn’t happen,” she says. “It’s a hard thing to face. You are afraid of how it is going to define and change you.” But now “I am more stable and can revisit it without it crippling me.”

She doubts she’ll win any convictions: “There’s no evidence. I’m not going to be shocked or bothered when those guys don’t go to jail.” Mainly, Stevenson says, she wants to pressure law enforcement officials to take rape cases very seriously—in the same way that civil rights activists pressured police to prosecute racial discrimination cases during the 1960s. “It required people coming forward and bringing cases,” she says, “and getting investigations to actually happen.”

Working on the case has inspired her to apply to law school. “When I’m done, hopefully I’ll be taking cases like this, for victims,” she says. “And being the kind of person who won’t walk away.”