In yesterday’s post, I explained that large agribusiness corporations largely avoid the task of actually growing food, leaving it mainly to family-owned farm enterprises. Why would they do that?

In short, it’s because most farmers grow commodities—and the laws of supply and demand make it virtually impossible to earn big profits from them.

Consider the cases of corn and soy. Together, the two crops take up more than half of US farmland and serve as the raw materials for nearly our entire food industry, providing everything from livestock feed to fats, sweeteners, and a litany of ingredients. (And that’s not to mention their newly prominent role in fueling our cars.)

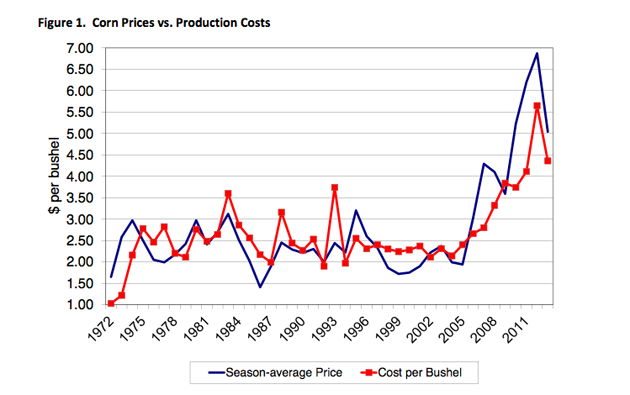

A lot of people see the big-time corn and soy farmers of the Midwest as fat cats, harvesting big bucks from on high in their vast, high-tech combines. Yet even with crop subsidies and government-backed insurance, large-scale farming in the Corn Belt is a pretty awful business. Get a load of the below chart, recently promoted by Big Picture Agriculture and taken from a recent paper by Iowa State University economist Chad Hart. The blue line represents how much Iowa farmers get paid for their corn, while the red line tracks what it costs them to grow it: seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, land rents, etc.

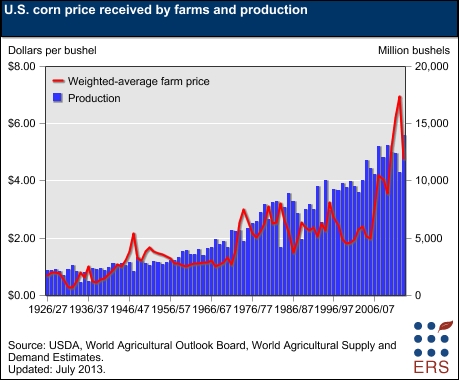

Note how, over the past 30 years, the red line often creeps above or intersects with the blue one. Each place that happens shows a time when farmers lost money or just broke even. If you want a longer view, the USDA has one for you, though note that the blue-red color coding is reversed in this one:

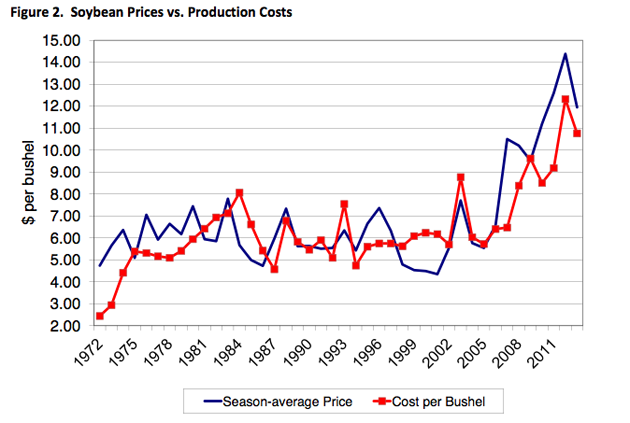

Maybe you think corn must be a loss leader, an off-year filler for its rotation-mate, soybeans, which rake in big profits? Not the case. Again, where the red line trends above the blue are times farmers lost money, on average:

What gives? Hart puts the story in devastating terms (emphasis added):

Agricultural returns tend to be cyclical in nature, a few years of good returns followed by a few years of negative returns. That is the inherent nature of agriculture; it is a competitive industry. And economic theory indicates the long run profitability of a competitive industry is zero. So we should expect some negative years to balance out the recent good run.

Zero long-run profitability—that’s a bracing thought when you’re thinking of, say, passing a farm operation on to your kids. Farming is hypercompetitive, especially if you’re operating in what economists call commodity markets—that is, producing a crop that’s functionally indistinguishable from that of your competitors.

The nice woman selling you tomatoes at the farmers market has all manner of ways of distinguishing her product—she’s offering such-and-such varieties, grown by this or that method, on some particular piece of land. And she has a range of customers—the teeming hordes of individuals who stream into farmers markets these days—to whom she can make her pitch. The customers may be price-conscious, but they came to the farmers market because they have more than just price in mind: Some combination of quality, locality, aversion to chemicals or what have you all factor into each buyer’s decision.

Now consider the farmer with 5,000 acres of corn and soy in Iowa. His products are essentially identical to those of hundreds of thousands of similar farmers—and not just in the US corn belt, but also in places like Brazil and Argentina. Their products won’t be sold to individual consumers. They’ll be mixed together and processed industrially and end up as, say, livestock feed, car fuel, or cooking oil.

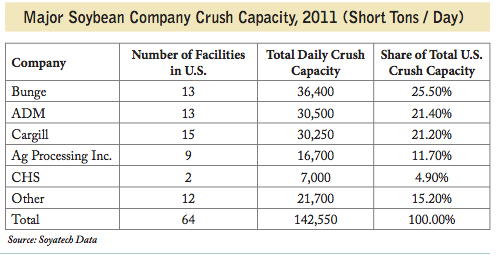

And there aren’t a lot of large-scale buyers out there to give the farmers options. Let’s say you’ve got a bin-busting harvest of soybeans to sell. Who are you going to turn to? This soybean-industry document has answers:

Note that just three companies control over two-thirds of US soybean processing; five control 85 percent of it. Similar conditions hold true in corn, as this document from the ace University of Missouri researcher and ag industry expert Mary Hendrickson shows.

The global trade in grain (a category that includes corn and wheat) is even more concentrated. According to a recent piece in Bloomberg Businessweek, a similar set of companies—Cargill, Archer-Daniels-Midland, Bunge, Louis Dreyfus, and Glencore Xstrata—”now control almost all the available grain handling assets in the world.” Unlike your farmers market shopper, these massive buyers want uniformity and low prices above all else—and they have the buying power to wring what they want out of their suppliers, i.e., farmers.

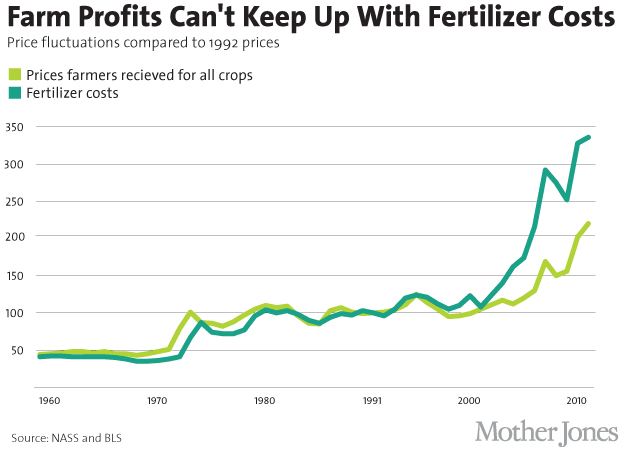

As the charts up top showed, corn and soy prices stayed pretty steady until around 2005, when they began an upward swing, borne up by the government-backed corn ethanol boom. Those charts also show that around the same time, farmers’ costs also began to creep higher.

Farmers have to buy all kinds of stuff to keep churning out those crops—fertilizer, seeds, pesticides, fuel. All of those make up the “production costs” line in those corn and soy charts. And as the charts show, they typically rise and fall with crop prices, keeping profit margins thin (or outright negative). If you drill down into recent prices for those major agricultural inputs, you’ll see the rises that are eating away at farmers’ profits.

Check out what has happened to the prices farmers pay for the synthetic nitrogen and mined phosphate and potash they use to fertilize their fields:

Again, fertilizer production is controlled by a small handful of companies. Take synthetic nitrogen—a fertilizer much beloved by most commodity corn farmers. Ammonia is the main ingredient in the nitrogen fertilizer farmers spread on fields. Four transnational companies—CF Industries, Koch Nitrogen, PCS Nitrogen Fertilizer, and Terra Industries—generate 72 percent of the ammonia produced in the United States, according to a December 2009 report from the industry research group IFDC. Another major nitrogen fertilizer product is urea, which is used both on farm fields and as a cheap protein enhancer in cow feed. For urea, those same four companies control nearly 84.8 percent of the market, IFDC figures show.

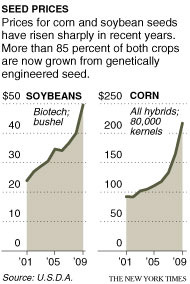

Then there’s seeds. Here’s the New York Times in 2010:

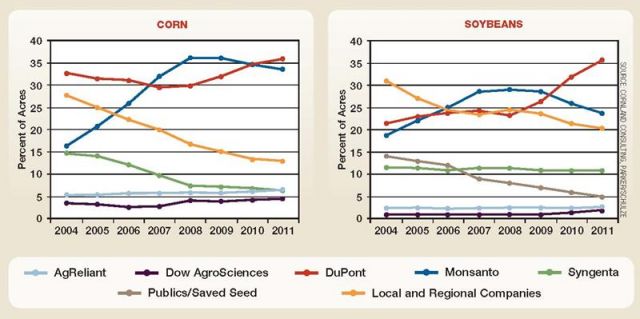

“Such price increases for seeds,” the Times reported, “are part of an unprecedented climb that began more than a decade ago, stemming from the advent of genetically engineered crops and the rapid concentration in the seed industry that accompanied it.” Biotech and agrochemical giants DuPont, Monsanto, Syngenta, and Dow took over the seed market in that period—their seeds now account for more than 80 percent of corn acreage, and 70 percent of soy acreage:

Source: Agweb.com

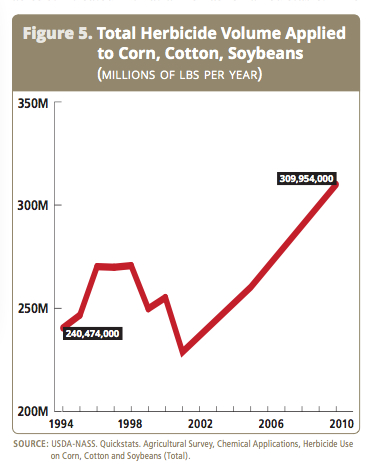

The great bulk of the seeds proffered by these dominant companies are engineered to withstand herbicides—which has given rise to a plague of herbicide-resistant weeds, and thus adding to farmers expenses in another way: by prompting them to use ever-more chemical herbicides. Here’s a chart from Food and Water Watch showing that rise:

Then there’s fungicides, another mounting expense in corn country. As I wrote in a recent post:

While the pesticide industry doesn’t release use data, the market research firm Lucintel recently estimated that the global fungicide market will increase at an annual compounded rate of 6.7 percent over the next five years. “North America witnessed the highest growth during the last five years and is expected to lead the industry during 2012 to 2017,” Lucintel added.

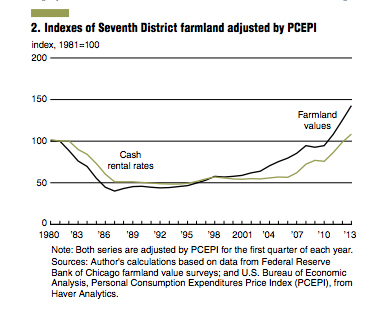

Finally, there’s land costs. When crop prices go up, farmland becomes more valuable, and landlords jack up rent. And rent is a significant cost to many farm operations. According to the USDA, 40 percent of US farmland is rented. Here’s the Federal Reserve on land rents in its 7th District, which encompasses farm-heavy Iowa and similar swaths of Illinois and Wisconsin. Note that rents have nearly doubled, in inflation-adjusted terms, since the mid-2000s:

So, while the last seven or so years have been relatively fat ones for US commodity farmers, now crop prices are coming down. Predictably, farmers—here in the United States and also in Brazil, that emerging industrial–agriculture powerhouse—have responded to high prices for corn and soy by planting more of both. As those fields fill out, the market is behaving as you’d expect: As the blue and red charts at the very top of this post show, the “price” and “cost” lines for the two crops are, once again, converging rapidly. As Iowa State’s Hart puts it, “We should expect some negative years to balance out the recent good run”—and through subsidies programs, including subsidized crop insurance, taxpayers will be on the hook to make up the difference.

Commodity farming is a terrible business for farmers, but a vital one. Societies can’t function without the food security represented by large stocks of shelf-stable crops like grains and oilseeds. And commodity farming, with its long-term zero profitability, can’t really function without public support. These days, that public support is geared in a way that works extremely well for the input suppliers—the handful of companies that provide the ever-pricier seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. In a follow-up piece—as Congress yet again tries to cobble together the next farm bill, which governs US ag policy—I’ll sketch out a way that farm policy could be used to benefit farmers, the environment, and the public at large.