Illustration: Ryan Snook

When I met Michael Bagley at the Hamilton, a cavernous watering hole two blocks from the White House, he was decked out like Sterling Archer: black turtleneck, black pants, black shoes. It seemed fitting for a man whose company—Jellyfish—sounds like it was ripped from the pages of a spy novel. The firm specializes in “political intelligence,” the fastest-growing Washington industry you’ve never heard of.

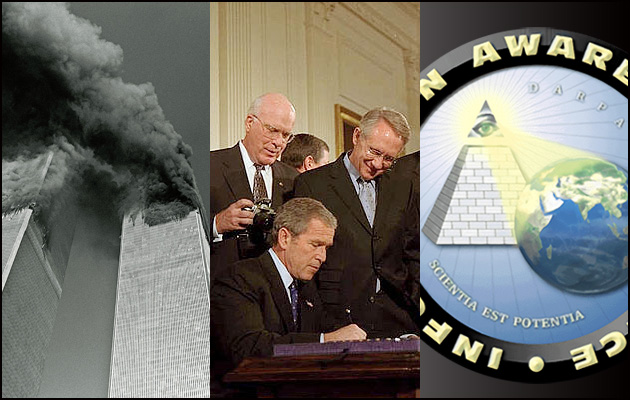

“What’s the old Gordon Gekko quote? Information is a valuable thing,” the 45-year-old Bagley said as he sipped his pale ale. Jellyfish collects information about what’s happening behind the scenes and rushes it to its corporate clients so they can make investments based on things like forthcoming regulations or tax code tweaks. Secrecy is a key selling point; the firm isn’t required to disclose its agents or customers. “So a company like Philip Morris would like a seat at the table, literally and figuratively,” Bagley said, somewhat reluctantly name-dropping his biggest client at the moment. “We provide that to them.” In addition to tracking legislative and regulatory wheeling and dealing, his shop connects clients with officials at places like US Central Command, the better to figure out, say, what impact overseas military operations could have on tobacco shipments. Bagley’s original associates were veterans of the security contractor Academi (formerly Xe, previously Blackwater) and Able Danger, a Pentagon program that was said to have identified Mohamed Atta before September 11.

Though Jellyfish traffics in knowledge that’s “nonpublic or not easily accessible to the public,” Bagley insisted that everything it does is aboveboard. “We work on unclassified information, but our information is based on relationships,” he explained. “Just like you and I are having a beer here, we’re just exchanging information. There’s nothing nefarious going on here.”

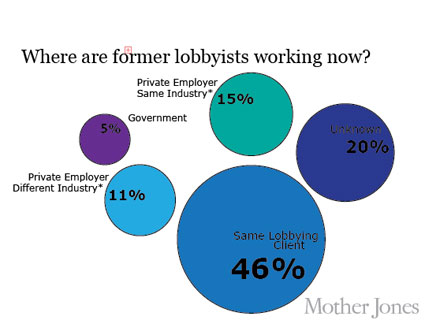

As Wall Street has pursued ever more complex ways to make a buck, the political-intelligence industry has boomed, bringing in $402 million in 2009, according to Integrity Research Associates, which tracks the PI sector. That’s still small potatoes compared to the $3.3 billion lobbying industry, but it has caught the eye of critics who worry that it amounts to selling special access to the public’s business. “This is basically the kind of thing that America hates,” says former lobbyist-turned-reformer Jack Abramoff.

Heather Podesta, a corporate lobbyist who once proudly sewed a scarlet “L” on her dress at a Democratic convention party, recalls the moment several years ago when she realized political intel had taken on a life of its own. Hedge funders had packed the audience at a Senate hearing on asbestos legislation. They had no interest in the policy implications; they just wanted to find out first so they could place their bets for or against the asbestos makers. “The whole thing,” Podesta tells me at the power-lunch staple Charlie Palmer, “was just so sleazy.” Yet so long as they don’t veer into insider trading or Abramoff-style shenanigans, the political-intelligence firms aren’t breaking any laws. “All they’re doing is discovering the information and conveying it,” concedes Abramoff, whose influence-peddling schemes swept up a half-dozen Republican lawmakers and landed him in prison. “I’m not even sure if you made it illegal there’s any way to enforce it. It’s ingenious.”

The political-intelligence industry began to take shape in the early 1980s. As federal regulatory power expanded, big business wanted to know what happened in obscure subcommittee hearings—and didn’t want to wait for the next day’s papers to read about it. In 1984, investment banker Ivan Boesky hired lobbyists to attend committee hearings about a big oil merger and report back to him. It paid off: Boesky made a cool $65 million just by finding out first and buying low. “Investors started to realize that there was money to be made by knowing what was going on in Washington and knowing it as quickly as possible,” says Michael Mayhew, the founder of Integrity Research Associates.

As Wall Street put an ever-greater premium on speed, investing in supercomputers to place orders milliseconds before the competition, the industry took off. The biggest known score came in 2005, when Congress was weighing approval of a $140 billion trust fund for asbestos liability claims at the hearings Podesta witnessed. A few days before then-Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R-Tenn.) announced a vote on the plan, hedge funds snapped up stock in companies that would be shielded from lawsuits if the fund were set up. The Securities and Exchange Commission suspected that advance notice of the vote had leaked from the senator’s office to lobbyists who then tipped off their political-intelligence clients. That the asbestos fund ultimately never came to be was beside the point; the hedge funds had already made their money.

In 2006, Rep. Louise Slaughter (D-N.Y.) introduced the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge (STOCK) Act, which banned insider trading by members of Congress and their staffs. It also mandated that firms that specialize in information peddling (journalists excepted) register and disclose their clients and payments. But in the final version passed last year, that provision was removed after a furious lobbying push. “I didn’t even realize we were going to get hit with that type of opposition,” says Craig Holman, a lobbyist for Public Citizen. “Wall Street brought out their guns.” Much of the pushback came from the Securities Industry and Financial Market Association, which spent more than $5.5 million lobbying Congress last year.

Transparency advocates admit that there’s a lot they don’t know about how the industry works, which is one reason they suspect it’s up to no good. “It sounds cloak-and-dagger, but what the heck: There’s billions of dollars involved here,” says former Rep. Brian Baird (D-Wash.), a sponsor of the STOCK Act. “It’s only a matter of time before there’s going to be a massive scandal,” says one Republican Senate staffer.

It is hard to define what exactly constitutes political intelligence, much less when it crosses the line between research and sleaze. In April, a firm called Height Securities alerted its clients to an imminent change in Medicare Advantage rates, prompting them to buy up health care stocks. Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) launched an investigation into how the company got its inside information, yet so far there’s been no evidence of wrongdoing. When I called Bagley in late summer, he told me that Jellyfish had rearranged its operations to focus on foreign governments, citing the “lack of continuity in what the definition of political intelligence is, was, and was going to be.”

What likely won’t change, though, is the commodification of policy as K Street increasingly caters to the financial industry. “What is it Wall Street wants?” asks Barbara Dreyfuss, a former political-intelligence analyst who’s now an investigative reporter. “They want quick action. They want insider information that only they know that will give them quick action. And that’s because Wall Street has become a speculative bonanza.”