Courtesy of <a href="http://gravitymovie.warnerbros.com/#/gallery/11">Warner Bros.</a>

Holy shit.

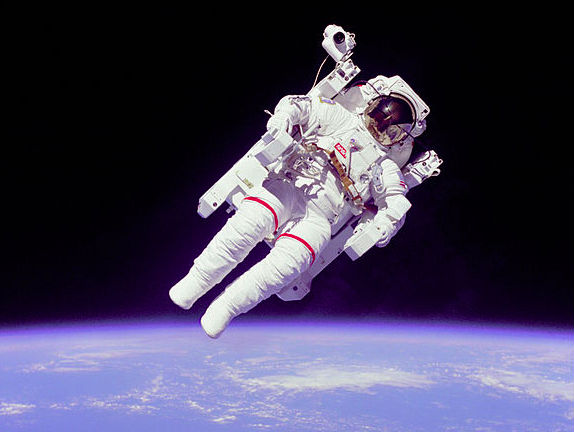

Those are two words you’ll be thinking a lot when you watch Gravity, the new film from writer/director Alfonso Cuarón. The film stars Sandra Bullock and George Clooney, who play two NASA astronauts stranded in space after satellite debris turns their mission into harrowing hell. The visuals and drama are jaw-dropping. Director James Cameron has called it “the best space film ever done,” featuring the “best space photography ever done.” Bullock, who occupies most of the screen time, delivers a flooring, commanding performance. And to prepare, she sought out the advice and wisdom of one NASA astronaut: Catherine “Cady” Coleman.

Cuarón and his team didn’t spend much time consulting NASA for the film. However, Bullock did reach out to Coleman, a retired US Air Force colonel and astronaut who has been at NASA for 21 years and has spent 180 days in space aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia and the International Space Station. Coleman lives in Houston and commutes back and forth from her family home in Massachusetts. When she’s not being launched into space, she enjoys playing music, mainly on her flute. The first time Bullock and Coleman communicated, Coleman was aboard the ISS, orbiting somewhere between 230 and 286 miles above the Earth’s surface.

“It took a couple email cycles because I only got to email four times a day in space,” Coleman tells Mother Jones. “After you reply, they don’t get your email for another four hours.” After they finally connected, the two chatted over the phone a few times about life in space and floating in microgravity. “Sandra wanted to know how we move up there, when we’re still and when we’re not still, what it was like in a space suit,” Coleman says.

“How come we don’t get to talk to Sandra Bullock?” joked the male members of her crew, including Ron Garan, who would make lighthearted comments such as, “Ah, you talked to Sandra, didn’t you…Did she ask about me?”

Gravity gets a wide release on October 4, and critics, by and large, are very pleased. It appears as though Coleman is, as well. “What I love about this movie is that it takes people from this planet,” Coleman says. “When I met the director, he said, ‘I can’t believe you’ve been in space!’ I just said to him, ‘I can’t believe you haven’t been in space, because you made this movie!’ It’s a big privilege for me to have this view of our place in the universe, and now audiences get to feel some of the things I feel…What the film shows in a very sensational way are things [NASA astronauts] think about in a very ordinary way, and treat very, very carefully.”

In crafting Cuarón’s vision, the director’s team actually developed their own technology to properly simulate the weightlessness and light reflection of the disastrous space mission. Despite the crew’s best efforts, space fans and NASA buffs will indeed have some details to quibble over. To have Clooney and Bullock’s characters to “zip over [from their destroyed shuttle] to the space station would be like having a pirate tossed overboard in the Caribbean swim to London,” Dennis Overbye, who saw the film with NASA astronaut Michael J. Massimino, wrote in the New York Times last month. Coleman has her own notes on film vs. reality. “We also wear a jetpack, but it just doesn’t have as much fuel as George’s, which is unfortunate,” Coleman says. “We wouldn’t exactly have someone zipping around the way George does [for fun in the beginning of the movie]; we’d be out there working.”

Coleman says that NASA astronauts rarely have to deal with the kind of life-threatening orbital debris that Kowalski and Stone face in Gravity‘s thrilling set pieces. (Dangerous satellite debris and space junk are real problems that NASA is trying to tackle, though. In 2007, China blew up one of their own satellites in a controversial missile test, and astronauts are still dealing with the consequences of that debris.)

But movies are, of course, movies. The dread and intensity of Gravity are (as you could guess) about the furthest thing from Coleman’s experience. “I loved it up there,” she says. “If it weren’t for my family, I wouldn’t have wanted to come home…There’s so much to do, so much research to do [at the ISS.]”

One passion Coleman gets to indulge, whether she’s on Earth or hovering far above it, is her love for music. (She’s played in a band with Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who is famous for playing David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” in space.) When she isn’t jamming, she prefers listening to folk music, as well as hits from the ’80s and ’90s. Coleman is perhaps the only astronaut to play the Jethro Tull frontman’s flute in space. “I reached out to Ian Anderson, saying I’d like to bring a flute with me, and he said yes!” Coleman says. And in 2011, during a live NASA broadcast on Saint Patrick’s Day, she played a hundred-year-old flute that belonged to Matt Molloy of the Irish band the Chieftains. A recording of this performance is included in “The Chieftains in Orbit” on the 2012 album Voice of Ages. “It was thrilling to see my name on something that was on sale at Starbucks,” she says. Here’s a screenshot of the gig:

(Coleman is also a fan of the arts and culture coverage on National Public Radio. In fact, Coleman was the first astronaut to ever request that NPR be transmitted to the ISS. Those aboard the space station can now listen to NPR broadcasts every day.)

And the release of Gravity presents Coleman with another way to reach people through entertainment, if only indirectly. In a conversation with Bullock featured on NASA Television, Coleman mentioned that she let her hair grow longer in space, because she wanted it to “scream, ‘zero-g, there is a woman in space,'” for the impressionable girls out there. “Another part of movie that was important to me was that it was nice for a woman to be the main character—she runs into trouble, she perseveres, she’s a good role model for girls,” she says. “It’s great for them to see it as normal for a woman to be the hero in a film that takes place in space.”

Right now, Coleman has no plans to extend her brief foray into Hollywood. She is, however, excited to get back up to the space station—it’s just tough to tell when exactly that will be. “I’m in line,” she says. “The line is long, and the line changes shape all the time.”