Unemployment is bad. Obviously long-term unemployment is worse. But it’s not just a little worse, it’s horrifically worse. As a companion to our eight charts that describe the problem, here are the top ten reasons why long-term unemployment is such a national catastrophe:

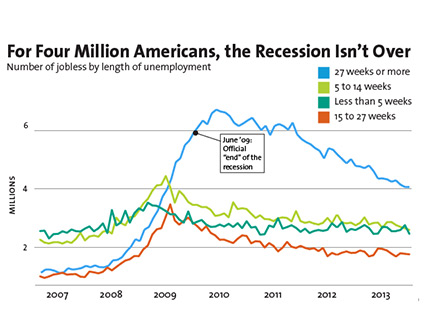

- It’s way higher than it’s ever been before. When the headline unemployment rate peaked in 2010, it was actually a bit lower than the peak during the 1980 recession and only a point higher than the 1973 recession. As bad as it was, it was something we’d faced before. But the long-term unemployment rate is a whole different story. It peaked at a rate nearly double the worst we’d ever seen in the past, and it’s been coming down only slowly ever since.

- It’s widespread. There’s a common belief that long-term unemployment mostly affects older workers and only in certain industries. In fact, with the exception of the construction industry, which was hurt especially badly during the 2007-08 recession, “the long-term unemployed are fairly evenly distributed across the age and industry spectrum.”

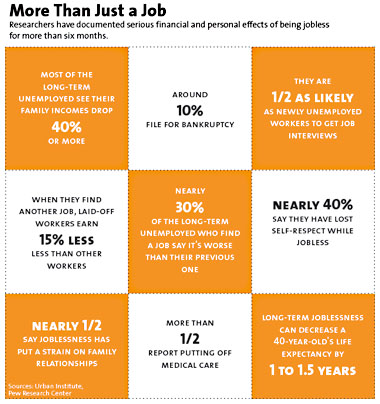

- It’s brutal. Obviously long-term unemployment produces a sharp loss of income, with all the stress that entails. But it does more. It produces deep distress, worse mental and physical health, higher mortality rates, hampers children’s educational progress, and lowers their future earnings. Megan McArdle summarizes the research

findings this way: “Short of death or a debilitating terminal disease, long-term unemployment is about the worst thing that can happen to you in the modern world. It’s economically awful, socially terrible, and a horrifying blow to your self-esteem and happiness. It cuts you off from the mass of your peers and puts stress on your family, making it likely that further awful things, like divorce or suicide, will be in your near future.”

findings this way: “Short of death or a debilitating terminal disease, long-term unemployment is about the worst thing that can happen to you in the modern world. It’s economically awful, socially terrible, and a horrifying blow to your self-esteem and happiness. It cuts you off from the mass of your peers and puts stress on your family, making it likely that further awful things, like divorce or suicide, will be in your near future.” - It’s long-lasting. Cristobal Young reports that “job loss has consequences that linger even after people return to work. Finding a job, on average, recovers only about two thirds of the initial harm of losing a job….Evidence from Germany finds subjective scarring of broadly similar magnitude that lasts for at least 3 to 5 years.“

- It dramatically reduces the prospect of getting another job. There’s always been plenty of anecdotal evidence that employers don’t like job candidates who have long spells of unemployment, but recent research suggests that this attitude has become even worse in the current weak economy. Rand Ghayad, a visiting scholar at the Boston Fed, sent out a bunch of fictitious resumes for 600 job openings. Each batch of resumes was slightly different (industry experience, job switching history, etc.), and all of these things had a small effect on the chance of getting a callback. But one thing had a huge effect: being unemployed for six months or more. If you were one of the long-term unemployed, it was all but impossible to even get considered for a job opening.

- It turns cyclical unemployment into structural unemployment. What we’ve mostly had during the Great Recession and the subsequent recovery has been cyclical unemployment. This is unemployment caused by a simple lack of demand, and it goes away when the economy picks up. But structural unemployment is worse: it’s caused by a mismatch between the skills employers want and the skills workers have. It’s far more pernicious and far harder to combat, and it’s what happens when cyclical unemployment is allowed to metastasize. “Skills become obsolete, contacts atrophy, information atrophies, and they get stigmatized,” says Harry Holzer of Georgetown University.” Economists call this effect “hysteresis,” and there’s plenty of evidence that we’re suffering from it for perhaps the first time in recent American history.

- It hurts the economy. A recent study, which Paul Krugman called the “blockbuster paper” of last month’s IMF research conference, concludes that “by tolerating high unemployment we have inflicted huge damage on our long-run prospects.” How much? The authors suggest that not only has it cut GDP growth, it’s even cut potential GDP growth. They estimate the damage at about 7 percent per year—which represents a loss of roughly $3,000 for every man, woman, and child in the country.

- Cutting off unemployment benefits makes things even worse. Cutting off benefits obviously hurts the unemployed in the pocketbook. But there’s more to it than that. Since you have to keep looking for a job to qualify for benefits, many discouraged job seekers have less incentive to keep looking when their benefits run out. This means they drop out of the official numbers and are no longer counted as formally unemployed. In other words, because we’ve allowed unemployment benefits to expire

for so many people, the real long-term unemployment rate is probably even worse than the official figures say it is.

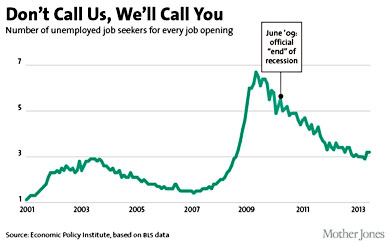

for so many people, the real long-term unemployment rate is probably even worse than the official figures say it is. - There still aren’t enough jobs to go around. In a normal economy, there might be good reason to keep unemployment benefits short: it motivates people to go out and look for work. But that’s not the problem right now. The number of job seekers for every open job has declined since its 2009 peak, but there are still three job seekers for every available job, which means that this simply isn’t a matter of incentives. It’s a matter of there being too few jobs for everyone. Conservative scholar Michael Strain uses a simple analogy to get this point across: “If you look at the long-term unemployed, a good chunk of them have children. A good chunk are married. A good chunk are college-educated or have had some college and in their prime earning years….It strikes me as implausible that this person is engaged in a half-hearted job search.”

- Practically everyone, liberal and conservative alike, agrees that this is a catastrophe. And yet, we continue to do nothing about it. Republicans in Congress have declined to extend unemployment benefits further, and they show no sign of changing their minds when Congress reconvenes in January. Democrats have a plan to fight for further benefits by linking them to a farm bill that Republicans want to pass, and right now that’s pretty much the best hope we have to offer the workers who have been most brutally savaged by the Great Recession.