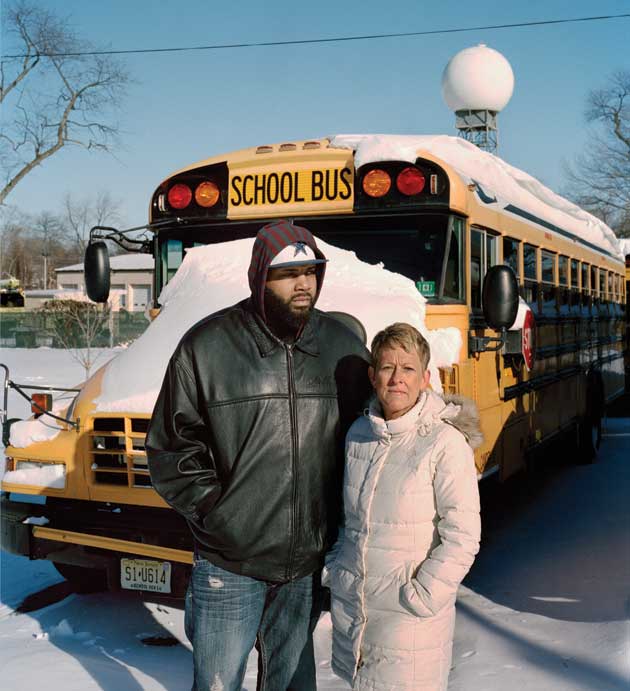

Kathryn Edin, Joe White, and his daughter JanasiaPhotos by Mustafah Abdulaziz

Blond and midwestern cheerful, Kathryn Edin could be a cruise director, except that instead of showing off the lido deck, she’s pointing out where the sex traffickers live off a run-down strip of East Camden, New Jersey. Her blue eyes sparkle as she highlights neighborhood landmarks: the scene of a hostage standoff where police shot a man after he’d murdered a couple in their home and abducted their four-year-old; the front yard where a guy was gunned down after trying to settle a dispute between his son and two other teens.

Edin, 51, talks to every stranger we pass. She chirps hello to some guys working on a car jacked up in their front yard, some dudes selling pot, and a little girl driving a pink plastic jeep on the sidewalk. Most of them look at her like she’s from another planet—which in a way, she is.

A sociologist at Johns Hopkins University, Edin is one of the nation’s preeminent poverty researchers. She has spent much of the past several decades studying some of the country’s most dangerous, impoverished neighborhoods. But unlike academics who draw conclusions about poverty from the ivory tower, Edin has gotten up close and personal with the people she studies—and in the process has shattered many myths about the poor, rocking sociology and public-policy circles.

For three years Edin lived with her family in a studio apartment smack in between the two crime scenes we just passed and a few blocks from one of the city’s largest and most notorious public housing projects. Here she spent years doing intensive fieldwork for her latest book, coauthored with husband and Johns Hopkins colleague Tim Nelson, on low-income, unwed fathers. Doing the Best I Can: Fatherhood in the Inner City is a complicated portrait of a group of people all but ignored by statistics-driven social-science research—in large part because there’s little ready-made data about them.

Disconnected from a welfare system that historically has helped researchers track single moms, these men are also often untethered from traditional institutions such as schools and churches. The places where you can find clusters of them—prisons and drug rehab programs—give you a skewed sample. And there’s a more basic problem, well documented in research: When sociologists ask whether they have kids, some men don’t know—or lie.

To get around these issues, Edin spent years getting to know low-income fathers, drawing them out to talk about their love lives and use of birth control, their reaction to pregnancies, and other intimate details. The result goes beyond the welfare-queen-style anecdotes that drive headlines and policy discussions, and instead gleans truth from ordinary experiences.

“Conventional wisdom is that the moms are the only ones who care about the kids and the dads want to flee responsibility,” Edin says. But she and Nelson found that the reviled “absentee father” isn’t quite so absent, nor does he want to be, and that whether he’s a deadbeat depends a lot on which of his kids you’re talking about.

Sociologist William Julius Wilson, one of the nation’s foremost chroniclers of inner-city poverty, heralds Edin’s work as groundbreaking. “I do research in those neighborhoods, and I found those stories quite revealing,” he says. “She uncovered things I hadn’t even thought about. I thought there would be some apprehension or concern that [the men] got a girl pregnant, but these guys were happy that they’d fathered a child. A child represented a life preserver for some of these guys.”

In the book, Edin and Nelson take as a starting point the public freak-out about the rise in unwed parenthood, a problem first highlighted by Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.) back in 1965 with the infamous report “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.” Then an assistant labor secretary in the Johnson administration, Moynihan warned that the black family was on the verge of a “complete breakdown”—at the time, 1 in 5 black children was born out of wedlock. Today, it’s more than 1 in 3.

Unwed black fathers continue to be singled out for special scorn by everyone from conservative gadfly Gary Bauer (who blames them for crime among NFL players) to President Obama, who in 2008 told black churchgoers in Chicago that “what makes you a man is not the ability to have a child” and pledged to address the “national epidemic of absentee fathers.”

Over the past two decades, such views helped unleash a torrent of punitive policies aimed at raising the cost of unwed fatherhood. Yet the share of those having kids out of wedlock has continued to soar. In 1990, 28 percent of American births were to unmarried women. Today, it’s a record 41 percent, with much of the increase coming among low-income whites. More than a third of all children with single mothers live below the poverty line, four times the rate of those with married parents.

Conservatives have blamed the shift on cultural decay, immorality, and welfare benefits. Liberals have flagged the disappearance of well-paying manufacturing jobs. But when Edin started her research, it was clear that none of these explanations told the whole story. The disappearance of marriage was a true social-science mystery.

So she and Nelson decided to embed with their subjects. In 1995, while teaching at Rutgers University, Edin, Nelson, and their three-year-old daughter moved into a studio apartment near 36th and Westfield in Camden, one of the poorest cities in America. It was the beginning of two years of intensive fieldwork, followed by another five years of interviewing—or, as Edin puts it, “a rich opportunity for learning. Some social scientists will rent an office building and bring people in and interview them. But experiencing what other people are experiencing while you’re studying them is just critical.”

Once a thriving industrial center, home of RCA Victor and the Campbell Soup Company, Camden saw decades of white flight as the manufacturing sector disappeared. By 2000, five years after Edin arrived, 53 percent of Camden’s residents were black, 39 percent were Hispanic, and 36 percent lived below the poverty line. The year she moved in was the city’s bloodiest on record, with 58 murders among 86,000 residents.

About a block away from the blue clapboard Victorian where Edin lived is the former Presbyterian church where she taught Sunday school—one of the ways she got to know people in the community, along with volunteering at an after-school program. On the warm fall day I visited, the voice of a holy roller bellowing at his flock rang clear across the street.

Teaching Sunday school wasn’t just a research ploy. Edin hails from rural Minnesota, where she “grew up in the back of the van” that her mother drove for a Swedish Lutheran church. She worked there with needy families whose kids often cycled in and out of jail and foster care. “The religious tradition I came up in was very focused on social justice,” Edin says, citing Micah 6:8 (“To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God”).

She attended North Park University, a small Christian college in Chicago with a social-justice focus. There, she took extra-credit assignments working in the notorious Cabrini-Green public housing project. In her free time she did things like watch Brother Sun, Sister Moon, Franco Zeffirelli’s film about St. Francis of Assisi, and walk around campus barefoot in the winter to emulate the saint.

Sunday school in Camden was different. One day, Edin recalls, she drew on a common evangelical trope, asking the kids what one thing they would save if their house were on fire. The answer is supposed to be “the Bible,” but for these kids the question was not a hypothetical. Most of the kids had actually been in that situation and could tell her exactly what they took. (Sometimes it was the Bible.)

Tragedy was endemic to her small class. In the space of a month, the fathers of two of the five students were killed in gun violence. Trauma made the kids “very vigilant,” she says. “They notice everything about you.” Some of their comments yielded unexpected insights for her research on low-income women’s attitudes toward marriage, which they tended to view as hard work more than a source of pleasure. “One girl said to me, ‘You white women are really into your husbands,'” she says with a laugh. “Watching people respond to you reveals a lot.”

Not long after she and Nelson moved in, a teenager avoiding pursuers jumped through an open bathroom window, then raced out their front door. She recalls the time she put her baby’s empty car seat down in the front yard while unloading groceries. When she turned around, it was gone. She ran down the street to a garage that served as the neighborhood’s unofficial flea market, and found it already for sale.

Edin says her willingness to put up with the same routine annoyances as her neighbors helped persuade them to open up. “Lots of people said, ‘We know you’re the real thing. You’re not here just to study us, because you live here, too.'”

She had some other things working in her favor, namely her family—which, in a way, was also a product of her research. In 1992, she was studying residents of a public housing project in Charleston, South Carolina, and volunteering at a food bank, where she befriended an African American woman who lived with her children in a tarp-covered shack with no running water. The woman asked Edin and Nelson to adopt her youngest child; they were about to go through with it when the child’s father stepped in to take custody. The wrenching loss inspired Edin and Nelson to formally pursue adopting.

They were incensed by ads in the local paper from white couples looking for a white baby. So they placed their own, reading, “white couple looking to adopt your black or biracial child.” The newspaper told Edin the text was illegal because it mentioned race, but eventually published it anyway. They received four calls within an hour and soon adopted a baby; their second child came via the New Jersey foster care system.

Raising young children in Camden, where nearly 75 percent of kids are born out of wedlock, proved to be a sociological study in itself. One day, she was out doing fieldwork when she spotted her three-year-old crossing Route 130, a major highway, trailing behind her teenage babysitters without anyone holding her hand. “It’s just an expectation of maturity that middle-class parents do not expect their kids to have,” she says. “When you’re poor and you’re a single mom, you have to raise your kids to be tougher and more savvy sooner.”

Edin came of age at a time when the country was engaged in a heated debate about whether the government should provide cash benefits to help single mothers and their children. Ronald Reagan had helped set the stage with his attacks on the “welfare queen,” and writers like conservative Charles Murray and liberal Mickey Kaus insisted that benefits made women lazy and encouraged them to have babies out of wedlock. Kaus and Murray didn’t base their arguments on any significant fieldwork. Murray went so far as to create a fictional couple to illustrate his argument. But their conclusions were shaping public policy nonetheless.

Edin stepped into this fight in the late 1980s while working on her master’s degree at Northwestern University. Sociologist Christopher Jencks had hired her to reinterview some of his subjects in a study on welfare. She’d been moonlighting by teaching college courses to welfare recipients, and one day Jencks asked what she was learning from her students. “Everyone cheats,” she said. Jencks perked up and said, “Can you prove it?”

Edin spent the next six years taking a deep dive into welfare home economics, pestering poor mothers in Chicago, Boston, San Antonio, and Charleston about how they managed to survive on benefits that averaged $370 a month. In 1997, she published her findings in a book called Making Ends Meet: How Single Mothers Survive Welfare and Low-Wage Work. It came on the heels of the Clinton-era welfare reform that overhauled the entitlement system to force single mothers into the workplace.

But Edin documented that most moms on welfare were already working under the table or in the underground economy, and that lovers, friends, family, and the fathers of their children were pitching in to help. They didn’t get legal jobs because of a straightforward economic calculus: Low wages drained by child care, transportation, and other expenses would have left them poorer than they were on welfare.

In a foreword to the book, Jencks notes that this simple math had been kept out of the political debate for years, as conservatives refused to admit that welfare benefits couldn’t support a family, and liberals were reluctant to acknowledge the extent of the deceptions. Edin’s work forced that discussion out into the open. “I don’t think we realize how difficult it is for low-income families living on minimum wage or less than minimum wage to survive,” says William Julius Wilson. “That’s why that book was so important—it documented what we should have known.”

Jencks says that Edin’s work also represented a “methodological innovation.” Rather than obsessing about getting a perfect sample for her study, he says, “she figured out that it was really better to get interviews and observations of people who were willing to trust you and would tell you the truth than it was to get interviews of people who were a random sample of the population who’d lie to you. That came as something of a shock to social scientists. The question of whether people were telling the truth had sort of slipped away.”

Next Edin took up the question of why low-income mothers so often put childbearing before marriage. Far from eschewing marriage as an institution, she found, poor women idealized it to such an extent that it became unattainable. They didn’t believe that a marriage born in poverty could survive.

In a society that increasingly saw marriage as a choice, not a requirement, low-income women were embracing the same preconditions as middle-class women. They wanted to be “set” before marrying, with economic independence to ensure a more equitable partnership and a fallback should things go bad. They also wanted men who were mature, stable, and who had mortgages and other signs of adulthood, not just jobs.

“People were embracing higher and higher standards for marriage,” Edin explains. From a financial standpoint alone, “the men that would have been marriageable [in the 1950s] are no longer marriageable now. That’s a cultural change.” The low-income women in Edin’s study reported that decent, trustworthy, available men were in short supply in their communities, where there were often major sex imbalances thanks to high incarceration rates. This, Edin found, was why low-income women were willing to decouple childbearing from marriage: They believed if they waited until everything was perfect, they might never have children. And children, says Edin, are “the thing in life you can’t live without.” As one subject explained, “I don’t wanna have a big trail of divorce, you know. I’d rather say, ‘Yes, I had my kids out of wedlock’ than say, ‘I married this idiot.’ It’s like a pride thing.”

Marriage was so taboo among her subjects that Edin discovered two couples in her sample who claimed they were unmarried at the time of their babies’ birth but were actually not. One of the women had even been chewed out by her grandmother for marrying the father of one of her children.

All through this research, Edin says, she’d never been interested in studying men. “It’s fun to write about people with a strong heroic element to the story,” she says. “Women have that. Men don’t have that. [They’re] more complicated; they’re dogged with bad choices.” In addition, she admits, “I felt hostile after writing about the women. I really had their point of view in my head.”

It was Nelson who, after years of working on a book about religious experience in a black church, convinced her otherwise. Together, they spent several years canvassing Camden in search of dads to interview. They stopped men on the street and asked if they’d talk—sometimes right there on the spot. They put up flyers and worked with nonprofit groups and eventually knit together a sample of equal parts black and white men they interviewed at length over the better part of a decade.

Again, what they discovered surprised them. Rather than viewing unplanned fatherhood as a burden, the men almost uniformly saw it as a blessing. “It’s so antithetical to a middle-class perspective,” Edin says. “But it finally dawned on us that these guys thought that by bringing children in the world they were doing something good in the world.” Everything else around them—the violence, the poverty, their economic prospects—was so negative, she explains, a baby was “one little dot of color” on a black-and-white canvas.

Only a small percentage of the men, black or white, said the pregnancy was the result of an accident, and even fewer challenged the paternity. When the babies were born, most of the men reported a desire to be a big part of their lives. Among black men, 9 in 10 reported being deeply involved with their children under the age of two, meaning they had routine, in-person contact with their kids several times a month. But that involvement faded with time. Only a third of black fathers and a quarter of white fathers were still intensively involved with kids older than 10. Among the reasons, Edin identifies unstable relationships with the mothers—the average couple had been together only about six months before conceiving a child. The men also frequently struggled with substance abuse and stints in prison.

Government rules also stood in the way of meaningful fatherhood. The welfare system tends to view an unwed father solely as a paycheck, not as a coparent. In many states, even unwed fathers who live with their children and pay some of the bills can be sent to jail for failing to pay child support. And men who do pay don’t necessarily get to see their child.

“At every turn an unmarried man who seeks to be a father, not just a daddy, is rebuffed by a system that pushes him aside with one hand while reaching into his pocket with the other,” Edin and Nelson write.

Edin sees in these obstacles to full-time fatherhood a partial explanation for what’s known as “multiple-partner fertility.” Among low-income, unwed parents, having children with more than one partner is now the norm. One long-running study found that in nearly 60 percent of the unwed couples who had a baby, at least one parent already had a child with another partner.

Multiple-partner fertility is a formula for unstable families, and it’s really bad for children, which Edin acknowledges in the book. But rather than view “serial dads” as simply irresponsible, Edin suggests that they suffer from unrequited “father thirst,” the desire for the intense experience of being a full-time dad. Consciously or not, they keep trying until they finally sort of get it right, usually with the youngest child, to whom they devote most of their resources at the expense of the older ones.

Some of these insights came from friendships Edin formed while living in Camden. She first met Joe White when he was a teenager participating in an after-school program run by Urban Promise, a nonprofit that helped Edin with her research and on whose board she now serves. White grew up in the notorious (and since-demolished) Westfield Acres housing project; his mom, who struggled with addiction, was once affiliated with a motorcycle gang.

I met White, now 36, at Urban Promise in September with Edin and Nelson. Sitting in the old church building that serves as its headquarters, White is a hulking and jovial figure in gray sweats, a sparkling white T-shirt, and sneakers. Before I can ask him a question, Edin jumps in, and I get a look at her technique in real time. She interrogates White, leaning forward with her blue eyes trained on him, hanging on his every word.

She urges White to talk about his life circa 1995, when they first met. Of the 58 people killed in Camden that year, “I knew at least 20 or 25 of those guys,” he says. “Because the city ain’t but so big.” He describes life in the projects: “Shoot-out right in front, come out to dead bodies.” As a teenager, he thought that after high school, “either you’re going to be a football player, or you look around and think, ‘I’m going to be dead when I’m 18.’ So when I got to 18, I was like, ‘Yeah!'”

Around that time, White discovered his girlfriend was pregnant. Ecstatic, he told his friends, “I just created a miracle!” White thought he’d overcome some pretty grim odds. “I’m going to be a dad, I’m 18, and I’m still alive! I’m passing a statistic,” he recalls.

White’s response to impending fatherhood was to look for an income. A number of the men in Edin’s book quit high school or college to work low-wage jobs trying to provide for their new children—giving up opportunities that would have helped them become better providers in the long run. Many turn to selling drugs because it pays better.

White began dealing as well. Eventually, he and his son’s mother split, and a few years later he had a daughter with another woman. But meanwhile, he’d started using drugs. At 24, he landed in a court-ordered drug treatment program and got clean. “My kids were my saviors,” he says. White’s girlfriend stuck with him, they had another daughter, and in 2006 they got married.

Today, White works full time at a screen-printing company, where he’s been for about 12 years, and spends his free time ferrying kids to sports practices and dentist appointments. He’s even got a house with a white fence—PVC, not picket—he put up himself.

Getting here hasn’t been easy. At one point, his first son’s mother, who now has two more kids, applied for welfare benefits. Even though White had always supported his son, the state automatically took him to court for child support, just as he got laid off from his truck-driving job.

His unemployment benefits were slow to come, so for about four months he had no income. The state threatened to revoke his commercial driver’s license. “My driving privilege was my job,” he says. He was able to pay in time to save his license, but the experience reinforced his sense that the welfare system “discourages a lot of guys from wanting to do the right thing. I’ve got family members right now who don’t even want to go work, because once child support gets done with their paycheck they’ve got $45, and that’s not enough to pay their bills,” he says.

Instead, they’re driven into the underground economy. “Don’t get me wrong,” White says. “There are some deadbeats out there that deserve that treatment. I’m not defending those guys. I’m defending the guys who actually take care of their kids regardless of a court order.”

As an academic, Edin generally shies away from policy recommendations. But she says the way to reunify families is not by beating up on men—particularly when the child support system doesn’t recognize the realities of the labor market. “To establish a set of policies that require you to be a superhero doesn’t make sense,” she says. “These men have a tremendous amount to contribute if we can just find a way.”

Not everyone comes to the same conclusions. Ron Haskins, a Republican architect of the Clinton-era welfare reform, is an old friend of Edin’s but thinks she’s being too kind to her subjects. Her book, he says, is “extremely valuable. But I think she put the best possible face on these young men. I think it’s possible to be much less sympathetic than she is. Someone has to start demanding that these guys shape up.”

Nonetheless, her research may already be prompting some changes. Joe Jones is the founder of the nonprofit Center for Urban Families in Baltimore, which works with low-income men, and serves on Obama’s Taskforce on Responsible Fatherhood and Healthy Families. He says Edin’s work has helped inform his effort in Maryland to pass legislation overhauling the welfare system to focus not just on women and children, but on couples and joint parenting. The bill would also offer men more access to job training and other supports that now go almost exclusively to women.

Edin, for her part, is on to another project. This one involves scouring the streets of Cleveland alongside Nelson, on a pair of purple cruiser bikes, to find the growing population of Americans living on less than $2 a day—”a third-world measure of poverty in first-world America,” Edin says.

In this pursuit, Edin has become obsessed with plasma centers. She now spends hours sitting in her car outside one, watching people come and go. She has zeroed in on a mother with no teeth who has raised herself since age 12 and recently lost her Walmart job after her aunt’s car died and she missed work. Edin is talking to people so poor they’re dependent on barter because they never have cash. One man she met is raising 12 children—four from his first wife, who just died of cancer, plus one of hers from another partner; three by his second, estranged wife, plus three of her kids from a previous relationship, and her niece. Since he lost his house in an eviction, they’ve all been squashed into his parents’ three-bedroom home, and he’s on the verge of losing the kids to foster care for lack of a bigger place to live.

Edin wants to tell stories like these to a larger audience to show how many people are not just struggling, but falling through the cracks entirely. When you lose the kind of low-wage, part-time work that dominates in places like East Camden, there are rarely unemployment benefits to cushion the blow. Welfare has been decimated, and food stamps can’t buy diapers.

Over a steaming bowl of chicken soup near the Urban Promise headquarters in Camden, Nelson and Edin marvel at how little policymakers know about the economic realities that poor people face. “You hear people say there’s not material poverty in the US,” says Nelson; census data, the argument goes, shows that most of America’s poor have TVs and air conditioning. But Edin—who is writing her first mass-market book on extreme poverty with colleague Luke Shaefer—*says the people they’re finding in Cleveland and other study sites “aren’t in the census.” Even she has trouble keeping track of her subjects. “They can just fall right off the map,” she says.

This is one reason why “people have been lulled into complacency thinking poverty is solved.” With the new book, Edin says, “we’re hoping to stoke the American conscience. These people are not a dependent class. They’re trying to do the right thing.”

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly implied that Nelson is a co-author of the mass-market book Edin is writing on extreme poverty. Her co-author for that book is another colleague, Luke Shaefer.