Bain Capital

It’s not unusual for the banking industry to challenge a new government rule. Ever since Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010, the banks have sent forth their army of lobbyists anytime federal regulators try to enforce a new restriction, often resorting to the courts if they don’t get their way. But their latest objection is particularly galling: They don’t want the government or public to know about the diversity—or lack thereof—within their industry.

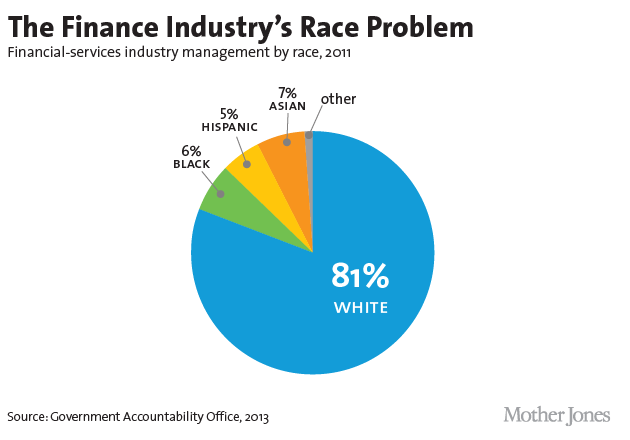

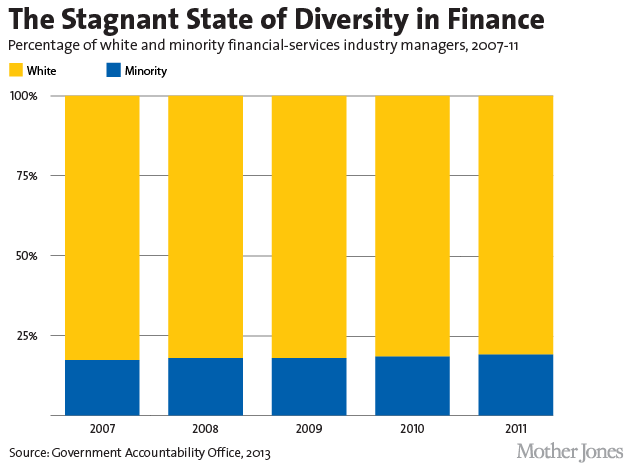

When Congress went about reforming the banking industry in 2010, Democrats made a specific point to encourage the financial industry to diversify its workforce. It has long needed a fix. The financial trade is controlled by old, rich white dudes, a cohort that doesn’t accurately reflect the country’s shifting demographics. The problem only gets worse when you look higher up the chain of command. Overall management in the financial services industry is 81 percent white as of 2011. African Americans only account for 2.7 percent of senior-level staff in the financial industry, while women hold just 28.4 percent of upper management jobs.

Dodd-Frank, the Democrats’ bill to reform Wall Street following the crash, included a provision that creates Offices of Minority and Women Inclusion in each branch of the federal regulatory regime, such as the Department of Treasury and the Securities and Exchange Commission. (The provision doesn’t touch sexual orientation.) These new offices are tasked with boosting diversity within their own ranks and analyzing hiring practices of the businesses in their purview. Late last year, regulators from six of these offices wrote a rule, still in the proposal stage, to enforce the second half of that mandate. It’s a modest measure—a simple request that the banks conduct self-assessments based on a few best-practice guidelines, but it was enough to rile up the banks.

Complaint letters sent from the main lobbying arms of the financial industry to regulators show a concerted effort to avoid changing their hiring practices and to dissuade regulators from revealing the lack of diversity in the banking sector. “In an otherwise good-faith effort to utilize the joint standards and meet certain standards or metrics relating to ‘diversity,'” the Chamber of Commerce wrote in its letter, “regulated entities may inadvertently run afoul of federal workplace requirements by, for example, engaging in ‘reverse’ discrimination.” Smaller regional banks shared those concerns. The Missouri Bankers Association likened the agencies’ proposal to a “government mandated affirmative action program.”

A sense of fear at the thought that employee diversity assessments might become public pervades the various complaint letters. The heaviest criticism comes in a letter penned by a gang of lobbying groups that encompass much of the financial industry: Financial Services Roundtable, American Bankers Association, Consumer Bankers Association, and the Independent Community Bankers of America. Those groups say the government is in danger of overstepping the bounds of law by forcing companies to explore their diversity policies, adding that “it is important for the Agencies to acknowledge that information can be taken out of context all too easily and misused.”

The NAACP published a report last year that graded the five largest banks on their inclusion of African Americans in their workforces, each barely mustering a passing grade. Bank of America and Citibank were rated as the best at a C+, trailed by JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo each with a C, and US Bank receiving a dismal D+.

Making sure corporations match the demographic diversity of the country is an issue all businesses must confront. But it has particular ramifications for the financial industry. When the housing market crashed, the ill effects weren’t evenly distributed. Mortgage brokers had disproportionately peddled dangerous subprime mortgages to African American and other minority borrowers, leading to high rates of foreclosure for black and Latino borrowers when the market buckled. According to a 2011 study by the Center of Responsible Lending, 10 percent of all African American borrowers had been foreclosed on, with another 14 percent on the verge of losing their homes. Just 5 percent of white borrowers had been kicked out of their houses. The racial imbalance transcends class-boundaries: 15 percent of high-income Latino borrowers had lost their homes by that point.

“There’s a recognition that there are changing demographics in the country,” Stuart Ishimaru, head of the diversity office at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, tells Mother Jones. “There’s certainly a thought that if you have a more diverse workforce and if you have a more diverse group of suppliers, that institutions very well could do a better job understanding a more diverse marketplace and how to best serve it.”

Regulators will weigh these complaints from the financial sector before finalizing the rule. It’s not a particularly aggressive measure. Because it hits a wide swath of companies—some 70,000—there is a lot of flexibility and discretion built into it. “There is a desire for increased transparency,” Ishimaru says. “There’s a desire to give tools that the public and consumers can use. That will likely take some time I think, because right now we’re setting a baseline.”

The rule could change before it’s finalized, but for now, there will be no systematic examinations or repercussions for the financial institutions. Instead, the agencies allow the companies to conduct and submit self-examinations on their practices. The government encourages the companies to post these reports on their websites but, at least for now, that is their decision to make. The agencies recommend various practices to encourage diversification at the companies—hiring a senior-level executive devoted to the cause, for example—but don’t force any strict measures onto the banks.

The bank lobbyists counter with claims that these rules would place an unfair burden on smaller community banks. It would, in fact, be unreasonable to expect a small bank in a rural Minnesota to match the same standards of diversity as the national big banks. Their pool of job applications might be overwhelmingly white. But larger financial institutions certainly do not share the same recruiting challenges.

Despite the banks’ protestations, consumer advocates think the regulators didn’t go far enough with the rule. Americans for Financial Reform, a liberal advocacy group, said the agencies should force the banks to publicly disclose their assessment, because otherwise there would be no public accountability. As the group wrote in a comment letter, “Leaving the disclosures voluntary threatens to make the [Offices of Minority and Women Inclusion ], and their mission, essentially irrelevant.”

Charts by AJ Vicens