Thomas Jefferson was a smart dude. And in one of his letters to John Adams, dated June 27, 1813, Jefferson made an observation about the nature of politics that science is only now, two centuries later, beginning to confirm. “The same political parties which now agitate the United States, have existed through all time,” wrote Jefferson. “The terms of Whig and Tory belong to natural, as well as to civil history,” he later added. “They denote the temper and constitution of mind of different individuals.”

Tories were the British conservatives of Jefferson’s day, and Whigs were the British liberals. What Jefferson was saying, then, was that whether you call yourself a Whig or a Tory has as much to do with your psychology or disposition as it has to do with your ideas. At the same time, Jefferson was also suggesting that there’s something pretty fundamental and basic about Whigs (liberals) and Tories (conservatives), such that the two basic political factions seem to appear again and again in the world, and have for “all time.”

Jefferson didn’t have access to today’s scientific machinery—eye tracker devices, skin conductance sensors, and so on. Yet these very technologies are now being used to reaffirm his insight. At the center of the research are many scholars working at the intersection of psychology, biology, and politics, but one leader in the field is John Hibbing, a political scientist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln whose “Political Physiology Laboratory” has been producing some pretty stunning results.

“We know that liberals and conservatives are really deeply different on a variety of things,” Hibbing explains on the latest episode of the Inquiring Minds podcast (stream above). “It runs from their tastes, to their cognitive patterns—how they think about things, what they pay attention to—to their physical reactions. We can measure their sympathetic nervous systems, which is the fight-or-flight system. And liberals and conservatives tend to respond very differently.”

This is not fringe science: One of Hibbing’s pioneering papers on the physiology of ideology was published in none other than the top-tier journal Science in 2008. It found that political partisans on the left and the right differ significantly in their bodily responses to threatening stimuli. For example, startle reflexes after hearing a loud noise were stronger in conservatives. And after being shown a variety of threatening images (“a very large spider on the face of a frightened person, a dazed individual with a bloody face, and an open wound with maggots in it,” according to the study), conservatives also exhibited greater skin conductance—a moistening of the sweat glands that indicates arousal of the sympathetic nervous system, which manages the body’s fight-or-flight response.

It all adds up, according to Hibbing, to what he calls a “negativity bias” on the right. Conservatives, Hibbing’s research suggests, go through the world more attentive to negative, threatening, and disgusting stimuli—and then they adopt tough, defensive, and aversive ideologies to match that perceived reality.

In a 2012 study, Hibbing and his colleagues showed as much through the use of eye-tracking devices like the one shown above. Liberals and conservatives were fitted with devices that tracked their gaze, and were shown a series of four-image collages containing pictures that were either “appetitive” (e.g., something happy or positive) or “aversive” (showing something threatening, scary, or disgusting). The eye-tracking device allowed the researchers to measure where the research subjects first fixed their gaze, how long it took them to do so, and then how long they tended to dwell on different images.

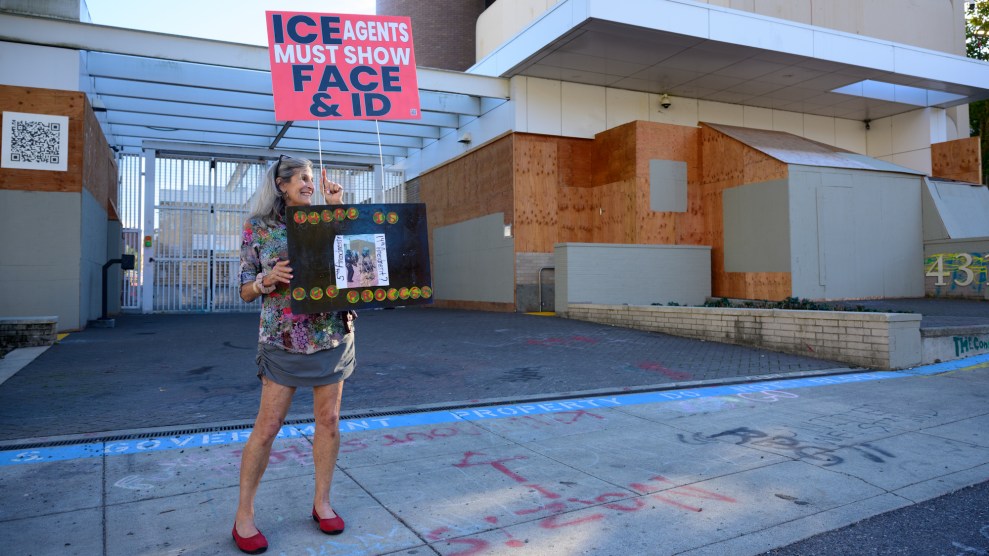

Here’s an example of an aversive, disgust-evoking image, one that just happens to also feature Hibbing himself. He says worms are actually “quite tasty.” (This picture wasn’t actually used in the study, but a very similar one was.)

And you can see an example of a four-image collage used in the study here. One of the images is adorable, the rest are varying degrees of disgusting and aversive. Which image does your eye go to first, and how long did you focus on it?

The results of Hibbing’s study were clear: The conservatives tended to focus their eyes much more rapidly on the negative or aversive images, and also to dwell on them for a lot longer. The authors therefore concluded that based on results like these, “those on the political right and those on the political left may simply experience the world differently.”

“Maybe you’ve had this experience, watching a political debate with somebody who disagrees with you,” says Hibbing. “And you discuss it afterwards. And it’s like, ‘Did we watch the same debate?’ And in some respects, you didn’t. And I think that’s what this research indicates.”

One of the biggest differences clearly involves the emotion of disgust. Hibbing isn’t the only one to have found a relationship between conservatism and stronger disgust sensitivity—this result is also a mainstay of the very influential research of moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt, who studies how deep-seated moral emotions divide the left and the right (see here). In one study, Hibbing and his colleagues showed that a higher level of disgust sensitivity is predictive not only of political conservatism but also disapproval of gay marriage. It is important to underscore that your disgust sensitivity is involuntary; it is not something under your control. It is a primal, gut emotion.

That word, “primal,” helps us begin to understand what Hibbing and his colleagues now think ideology actually is. They think that humans have core preferences for how societies ought to be structured: Some of us are more hierarchical, as opposed to egalitarian; some of us prefer harsher punishments for rule breakers, whereas some of us would be more inclined to forgive; some of us find outsiders or out-groups intriguing and enticing, whereas others find them threatening. Hibbing and his team have even found that preferences on such matters appear to have a genetic basis.

Thus, the idea seems to be that our physiology, who we are in our bodies, may lead us to experience the world in such a way that basic preferences about how to run society emerge naturally from more basic dispositions and habits of perception. So, if you have a negativity bias, and you focus more on the aversive and disgusting, then the world seems more threatening to you. And thus, policies like supporting a stronger military, or being tougher on immigration, might feel very natural.

And when you combine Hibbing’s research on the physiology of ideology with waves of other studies showing that liberals and conservatives appear to differ when it comes to genetics, hormones, moral emotions, personalities, and even brain structures, the case for politics being tied to biology seems pretty strong indeed.

So how do we then live with the other side—with those who disagree with us, for reasons over which they may not have full control? Hibbing believes that understanding that you don’t fully control your political orientation, any more than you do your sexual orientation or your left-hand/right-hand orientation, promotes political tolerance. “My dad was left-handed,” says Hibbing, “and he got beat on the hand with a ruler when he was a kid.” Nowadays, Hibbing continues, that would never happen—we’ve grown much more tolerant because we recognize that left-handed is just the way some people are.

So maybe the same can happen for politics. “We have this silly and naive hope, maybe it’s more than that,” says Hibbing, “that if we could get people to see politics in the same light [as left-handedness], then maybe we would be a little bit more tolerant, and there will be a greater opportunity for compromise.”

To listen to the full Inquiring Minds interview with John Hibbing, you can stream below:

This episode of Inquiring Minds, a podcast hosted by neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas and best-selling author Chris Mooney, also features a discussion of whether we are finally on the verge of curing AIDS, and new research (covered by Grist here) suggesting that great landscape painters, like JMW Turner, were actually able to capture the trace of volcanic eruptions, and other forms of air pollution, in the color of their sunsets.

To catch future shows right when they are released, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes or RSS. We are also available on Stitcher and on Swell. You can follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook. Inquiring Minds was also recently singled out as one of the “Best of 2013” on iTunes—you can learn more here.