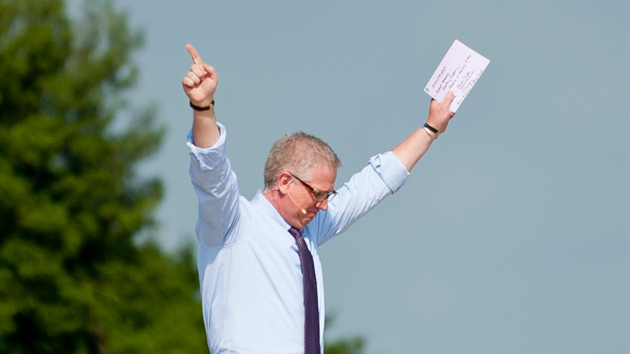

Pete Marovich/ZumaPress.com

On Tuesday, 40 minutes into Glenn Beck’s nationally broadcast “night of action” targeting the Common Core education standards being implemented in schools across the nation, a North Carolina activist named Andrea Dillon announced live that her state’s governor had just signed a law directing the board of education to rewrite its standards—a step shy of jettisoning North Carolina from the initiative outright. A murmur went through the audience of two dozen or so parents and kids at the cinema in Ballston, Virginia where I was watching, one of hundreds of theaters around the country that was broadcasting the interactive event, dubbed “We Will Not Conform”* (a nod to Beck’s new book on the standards, Conform). Beck offered a few words of congratulation, and Dillon patted her allies on the back: “North Carolina’s got a lot of gumption.”

It wasn’t the biggest political story of the night—that would be either David Perdue’s victory in the Georgia Republican Senate primary, or President Barack Obama’s consumption of multiple cheeseburgers, depending on your point of view. But Tuesday was a big day for opponents of the Common Core State Standards, a set of math and language-arts guidelines adopted by 46 states and the District of Columbia in 2010, and, of late, an object of obsession for Beck and his army of parent activists. North Carolina Republican Gov. Pat McCrory became the latest once-supportive governor to hop the fence in opposition to the standards. Last week, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker called on his state to repeal Common Core, echoing an earlier move by Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal to extricate his state from the standards. (That effort has turned the state board of education and Louisiana’s lieutenant governor against Jindal, and is now mired in litigation.) Meanwhile, in Georgia, where Republican officials in the state have previously been staunch supporters of the standards, an anti-Core teacher holds a narrow lead in the Republican primary for state superintendent—a position with broad powers for Core implementation.

The purpose of Beck’s event, which was sponsored by conservative advocacy group FreedomWorks and Liberty University’s online education platform, was to keep the momentum going. Similar to events Beck has held in the past, such as a semi-autobiographical one-man-show about a Christmas sweater, it was streamed live in movie theaters, many of which sold out despite the $19-a-ticket price tag. He had assembled a team of “generals”—activists, policy experts, politicians, and writers—who were leading the fight against Common Core and could teach attendees how to battle the initiative in their own communities. Beck’s guests sat at little tables in his company’s studio, which was once used for the filming of Barney and Friends and Walker: Texas Ranger. Following the broadcast, viewers would be presented with an “action plan” for combating Common Core, an education reform effort Beck has called “slavery” and “the most important story in American history.” The solution, he hinted, was to boycott the tests—and, in an unusual twist for a man known as a bombthrower, to turn down the rhetoric.

Midway through the event, Beck took a “potty break” and cut to his New York studio, where a host named Buck Sexton convened a focus group of parents and kids who opposed the Core. They sat at desks, just like in a classroom, and Sexton grilled them on questions like “Do you think you’re doing more work for no particularly good reason?” The kids, it turned out, don’t like homework, and think they get too much of it. “The best stuff that I’ve learned was stuff I taught myself on my own, but that comes with conservatism,” Sexton said, before throwing it back to Beck.

A cynic might suggest that this was all an elaborate plot to 1) make money, or 2) make more money by selling his anti-Common Core book, Conform—in bookstores now!, or 3) make even more money by peddling his book while building up his data lists by asking viewers to sign up for his text alerts during the event. But Beck told his audience the event was about something much greater. “The day we’re all willing to peacefully go to jail for our children like Martin Luther King was, we win.” It took him two hours and five minutes to mention Nazis, and only then in passing. This was a different side of the conservative media king—it was Glenn Beck, the community organizer.

As the event drew to close, Beck made one last appeal, requesting that they not use his name when they went back to their communities to talk to other parents about Common Core. “Don’t use ‘Glenn Beck’—no, seriously, don’t use ‘Glenn Beck,'” he said. For that matter, he said, parents should refrain from using the term “ObamaCore”—a popular nickname used by critics—lest they turn off would-be liberal allies. Instead, they should make an appeal to the heart. “There’s two things that will not be beaten—love and courage,” he said. And then he asked audience members to text 2233 for an instant notification when his action plan was released. But I considered my choices and opted out.

What am I, a conformist?

Correction: This article originally misstated the name of the event.