Illustration: Anita Kunz

Two decades ago, when I was writing what would be one of the first books on global warming, I interviewed a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, one of the few academics already thinking about the emerging problem. He hemmed and hawed for a little while, and then he said, “This is the public policy problem from hell. There are just too many conflicting interests. It won’t be solved.”

This December may be the last real chance to prove him wrong as the nations of the world meet in Copenhagen for a climate conference billed as make or break, do or die, perhaps quite literally sink or swim. In fact, you could make a fair argument that this will be the most important diplomatic gathering in the world’s history. Versailles, sure. Yalta, yes—but their failures were measured in decades of pain and millions of lives. Failure to rein in climate change will reverberate for tens of thousands of years, across generations not even yet imagined.

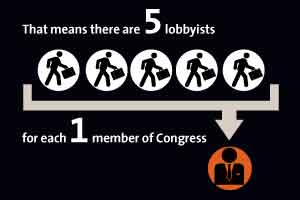

Which is not to say the 12 days of final negotiations will be august or easy to follow or even coherent. I remember the last big talks of this sort, in Kyoto in 1997. The sessions took place, as they will in Copenhagen, in a conference center miles from town. It became its own insulated world, with reporters and delegates and oil company lobbyists and NGO representatives endlessly querying each other about what was going on. (There was even a daily paper, and sometimes a parody version.) The answer to the queries was always the same: We’re waiting for the US and the Europeans to strike a deal. The official palaver was taking place in a big hall, with delegates making amendments and offering motions, but all the real action was behind closed doors.

The whole conference looked close to failure until Al Gore jetted in and instructed the US negotiators to “show flexibility.” That was just enough to allow the talks to limp to a conclusion— the midnight deadline passed, and by the next morning we were all being shooed out the door to make room for a molecular biology convention. No one had enough energy to give more than a feeble cheer for the final document, which in the end the US Senate never even considered ratifying.

This time around, America will be represented by a career political operative, Todd Stern, as chief climate negotiator. And probably Hillary Clinton. And quite possibly Barack Obama. They’ll be trying to satisfy the Europeans, who are again pushing for tougher cuts in emissions than the administration thinks are realistic. But this time the US/European divide isn’t the main challenge—far from it. This time the developing world has its own demands—and that will make a Copenhagen treaty far, far more complicated to arrive at than Kyoto was. For the developing world would like to…develop. And the most obvious way to do it is to burn coal. And they have an unimpeachable moral case, which goes like this: You got rich by burning coal, so why shouldn’t we?

You can imagine the game of multilevel chess that ensues: Everyone is under pressure from everyone else, and it all comes down to the final days, and most likely drags on into 2010 as the negotiators lurch toward some kind of middle ground. Which could mean, in the end, a treaty that at least moves us in the direction of the target that most people have been talking about for the last five years: holding temperature increases under two degrees Celsius and an atmospheric concentration of 450 parts per million (ppm) CO2. It won’t be easy by any stretch, and it won’t be any prettier than the Waxman-Markey bill now staggering through Congress. But a failure would be so embarrassing that there’s real pressure to agree to something.

SO THAT ABOUT COVERS all the factors. Except for two. Physics and chemistry, they’re called—and they’re throwing a serious monkey wrench into the proceedings. It started in the summer of 2007 when the Arctic melted with sudden and unexpected haste, 30 years ahead of what even the more pessimistic scientists were forecasting. And that’s after increasing the planet’s temperature about eight-tenths of a degree Celsius or slightly less than half of the two degrees that look like a best-case Copenhagen scenario. When the post-Kyoto negotiations began five or six years ago, we didn’t think one degree was enough to do real damage, but now we know different.

A few months after all that ice melted in 2007, our foremost climatologists gave us a new number to aim for: 350 ppm. NASA’s James Hansen and his team issued a series of papers showing that any atmospheric carbon content greater than that appears not to be compatible with “a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted.” In other words: Climate change is not a future problem for wise statesmen to patiently work to avert. It’s a right now, present tense, capital-E Emergency.

Hansen and his team warn that a world of 450 ppm CO2 is a world that will eventually be largely ice free. That will take some time—those Antarctic ice sheets are miles thick. But there’s plenty of change coming at us already. Dengue fever, carried by mosquitoes rapidly expanding their range in our newly warming world, has increased thirtyfold in the past 50 years. (A recent report indicated it could easily spread to more than half the states in the union.) Glaciers are melting before our eyes. (Glacier National Park will need a new name as early as 2020—the source of the Ganges could be a dusty hillside 15 years later.) Drought is becoming endemic across the American Southwest and in parts of Australia—some 200 people died this year around Melbourne when wildfires whipped through after a heat wave. A recent study predicted a 50 percent chance that Lake Mead, behind Hoover Dam, will have dried up by 2021. Meanwhile, since all the water that’s evaporating out of dry areas must eventually come back down, deluges (like the record rains in India that put a million people out of their homes in 2006) are getting worse. This is the kind of trouble you get at 387 ppm. You really want to go for 450?

If you had to pick a country to serve as a proxy for physics and chemistry at the Copenhagen talks, the Maldives would be a good place to start. This archipelago of 1,190 islands, most of them only a few feet above sea level, has a population of barely 400,000, so it won’t carry enormous clout in Copenhagen. It does have a certain moral authority, since under the deal that the EU and Obama are pushing for it probably won’t exist much longer. (See also “To the Lifeboats.”) To make matters worse, the islands depend on the fringing reefs that surround them for protection from waves and storms. But that coral is dying because the carbon in the atmosphere is turning the ocean more acidic. The pH of the sea—the whole damned Earth-girdling sea—has dropped from 8.2 to 8.1 and is apparently on its way to 7.8 in the lifetime of babies born today. In July marine scientists in London released a statement saying that long-term CO2 concentrations above 360 ppm will mean the death of all coral on the planet. Which explains why Mohamed Nasheed, the dynamic new president of the Maldives, says failure to reach agreement would amount to a “suicide pact.” And then there’s Bangladesh. There are the African countries already dying from drought. The UN raised a lot of new flags in the last century. Get ready to watch them start coming down.

It’s not that a treaty that would get us to 350 is impossible. Hansen and his team have shown that we could actually burn most of the oil in our wells (but sorry Canada, not the tar sands); if we were to stop burning coal by 2030, and sooner in the developed world, forests and oceans would eventually scrub enough CO2 to get us back to a safe level. Not without severe damage—we lack a method for refreezing the Arctic—but maybe on this side of catastrophe. But that’s heavier lifting than Obama and the Chinese have in mind, heavier lifting than even the EU is going to push for. It would require focusing the entire planet for a generation on the task of transitioning off fossil fuel. It would mean sticking whole industries with trillions of dollars in unrecoverable sunk costs (all those coal-fired power plants whose financing depends on a 40-year run). It would mean paying a huge political price. It would mean aiming for a solution, not an agreement.

To make it happen would require a movement, a movement big enough to push our leaders into truly uncomfortable decisions. Some of us have thrown ourselves into building 350.org, which is set to climax on October 24 with thousands of rallies across the planet. There will be teams of 350 bicyclists, and church bells pealing 350 times; in the Maldives, President Nasheed will lead 350 divers in the world’s largest underwater political demonstration. It may turn out to be the most widely dispersed political protest of all time, with actions happening almost everywhere. [Eds: You can show support by making your own personalized MoJo climate cover.]

But whether it will be enough to shift Copenhagen—that remains to be seen. The Maldives has promised to become the world’s first carbon-neutral nation by 2020. But it’s also started setting aside a portion of its budget every year to buy a new homeland. For the moment, global warming remains the problem from hell, and the planet is on a course to a remarkably similar temperature.