Richard Ross

Over the past 20 years, there’s been a promising decline in arrests of youths in the United States. The reasons for the drop are elusive, but one factor might be a renewed interest within the juvenile justice system in paying better attention to child welfare before kids are drawn to crime. States are also seeking alternatives to traditional punishment once kids are in the system.

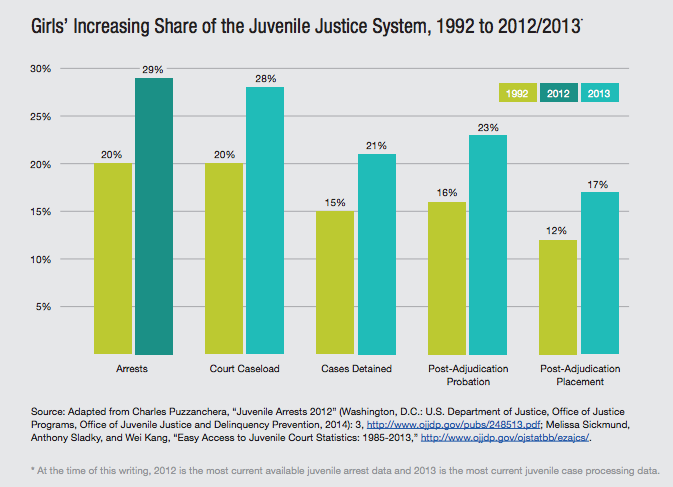

But a new report out this week finds that for young girls, the trend is going in the opposite direction. The proportion of girls in the juvenile justice system has increased at every stage of the process over the last 20 years, from arrests to detention and probation.

The report’s authors, Boston College law professor Francine Sherman and Annie Balck, a policy consultant at the National Juvenile Justice Network, attribute the gender gap to the juvenile justice system’s long-standing “protective and paternalistic” approach to dealing with delinquent girls. The system tends to detain girls, the authors write, because they’re seen as needing protection. It’s a strategy that is ill-suited to the personal histories of trauma, physical violence, and poverty that lead many girls into bad behavior. Even when the system acknowledges these factors, there are limited options available beyond traditional arrests and detention.

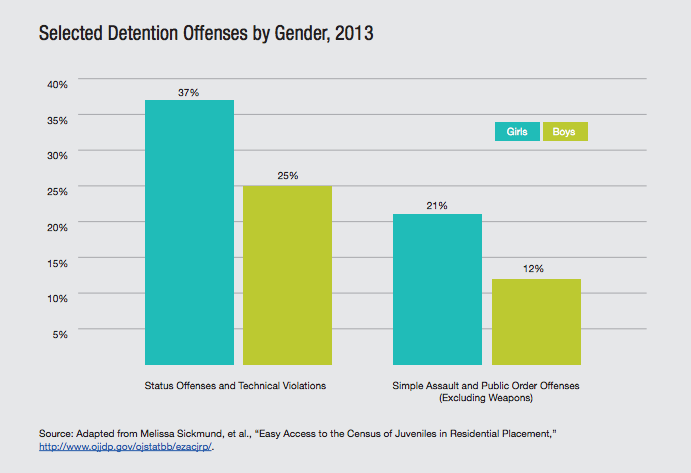

This report highlights several disparities in the treatment of girls in the system. For instance, there’s a gender gap in the detention of girls for low-level crimes: Nearly 40 percent of detained girls were brought in on status offenses (behavior that is only illegal when you’re under 18), compared with just 25 percent of boys.

Among girls in the system, there’s also stark racial inequity. In 2013, African American girls, the fastest-growing segment of the juvenile justice population, were 20 percent more likely to be detained than white girls, while American Indian girls were 50 percent more likely.

The authors also argue that detention is uniquely harmful to youths, and can lead to catastrophic consequences for girls. One study cited in the report found that girls who had been detained were five times more likely to die by age 29 than children who had not. For Latina girls, that likelihood increased—they were nine times more likely to die by age 29 than the general population. Detention is a drastic and developmentally incorrect measure to take, the report’s authors maintain, because in most cases the crimes girls commit are the result of past trauma that isn’t being properly addressed. Few have been found delinquent for more serious offenses such as assault.

The report cites a 2014 study of traumatic experiences in justice-involved youth. In the study, 31 percent of girls reported a personal experience of sexual violence in the home, 41 percent reported being physically abused, and 84 percent reported experiencing family violence. Girls reported having been sexually abused at a rate 4.4 times higher than boys.

“Greater restriction is rarely the answer and cannot address the violence and deprivation underlying so many girl offenses,” write the authors. To reverse the growing gender gap in juvenile justice, they say, “systems must craft reforms that directly address the root causes of their behavior and provide an alternate, non-justice-system path for girls’ healthy development and healing.”