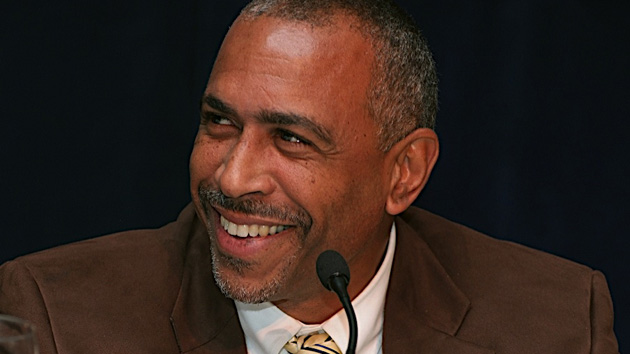

Secretary of Education John King, Jr. testifies during his confirmation hearing before the Senate Education Committee on February 25, 2016. Image courtesy of the US Department of Education on <a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/departmentofed/">Flickr</a>.

The Senate Education Committee confirmed John B. King Jr. as the nominee for the U.S. secretary of education on Wednesday morning. King’s nomination now goes to the full Senate for final approval.* If confirmed, King will step into the nation’s highest education policy post at a crucial time, when the states are working to implement the new Every Student Succeeds Act passed last December and will depend on King’s guidance.

Here are three things you need to know about Obama’s new education boss:

King is a fierce supporter of standardized testing and their use to grade students, teachers, and schools. Like his predecessor, Arne Duncan, who resigned in October last year, King promotes the most popular policies of the modern education reform movement—known for its passion for testing and ranking of teachers. Prior to becoming a senior adviser to Duncan in 2014, King was New York state’s education commissioner for three years. In that position, King presided over highly controversial, test-driven reforms that required, for the first time, new teacher evaluations based in part on student test scores. These changes were propelled mostly through federal Race to the Top grants that also encouraged New York and other states to implement Common Core standards and new tests and to open more charter schools.

These policies enraged many parents in New York—and in many other states—who were unhappy with the growing number of standardized tests their kids were taking. In 2014, a whopping 20 percent of all students in New York basically boycotted schools during testing days—the highest “opt out” rate in the country. Teachers in New York were also angry with King’s policies, pointing out that they didn’t have adequate time or materials to adopt the new Common Core standards and tests, and that they didn’t think test results should determine their pay and work security. In December 2014, King resigned in the middle of parent, student, and teacher backlash, and he joined the US Department of Education. (Last year, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo backed legislation that removed test scores from teacher evaluations for two years, something King vehemently opposed.)

In part, it was King’s positions in New York that pushed many opponents of the test-driven reform movement to send a letter opposing his nomination to the Senate Education Committee. In it, opponents like Jonathon Kozol, Naomi Klein, education historian and activist Diane Ravitch, and MacArthur grant teacher Deborah Meier warned legislators not to be “misled” by King’s “vague promises to do better.”

King is a big proponent of charter schools. In 1999, King founded the Roxbury Preparatory Charter School near Boston, which became the highest-performing urban public school in Massachusetts, according to NPR. After six years with Roxbury, King went to work as the managing director of Uncommon Schools, a chain of charter schools in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts that is famous for its emphasis on harsh discipline tactics and high test scores.

Advocates of charters like to argue that such schools provide a better model to educate poor Latino and African American students in large cities, but a number of recent studies suggest replicating outcomes like those at the Roxbury has been difficult on a large scale. A 2015 study by Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes looked at 41 urban cities and found that in a little more than half of them, charter students posted greater gains in test scores in math and reading than their peers in traditional schools. In the other cities, charter school students scored about the same or lower than their peers in noncharters. Another 2015 study by the University of California-Berkeley showed students who entered charter schools in Los Angeles were already higher achieving than their peers in traditional schools.

But King is not going to be a copy of Arne Duncan. King’s has deep roots in Brooklyn, New York, where his father was the borough’s first African American school principal. His mother was a guidance counselor born in Puerto Rico. By the time King was 12, he had lost both parents to illnesses. Despite a rocky adolescence, King went on to Harvard and later received graduate degrees from Yale Law School and Columbia University’s Teachers College. It is this inspirational personal story and background that make him an outlier in the education reform movement.

King credits his public school teachers for helping him stay on track, and his drive for improving schools, he often says, comes from a sense of urgency to create for other children the refuge that teachers created for him. “As a teacher, principal and policymaker, my goal is and has always been to give every student what Mr. Osterweil gave me—a classroom where they feel supported and inspired and challenged,” King said.

Pedro Noguera, a professor of education at the University of California-Los Angeles, points out that most people with the greatest power over school reforms in black and Latino communities—politicians like Rahm Emanuel or philanthropists like Bill Gates—are typically white, affluent, and don’t have their kids in public schools. As a result, issues like race, class, and segregation are not addressed by policy, Noguera told Mother Jones in 2015.

In contrast with Duncan, King has been a vocal supporter of racial and economic integration. During his tenure as commissioner in New York state, King created a small pilot program that offered grants to schools to integrate. King has said he wants to do the same nationally, and Obama’s new budget includes a request for $120 million to promote integration.

King will be different from Duncan in another important way: He won’t have as much power to dictate how schools must reform. As I wrote before, the big change in the new Every Student Succeeds Act bill is that it significantly reduces the power and the role of the federal government in expanding charters or grading and punishing schools, students, and teachers. States, not the feds, will now be responsible for making decisions on how to measure the progress of their students’ and how to reform their schools.

Correction: An earlier version of this article failed to mention that King’s confirmation by the Senate Education Committee has to be approved by the full Senate.