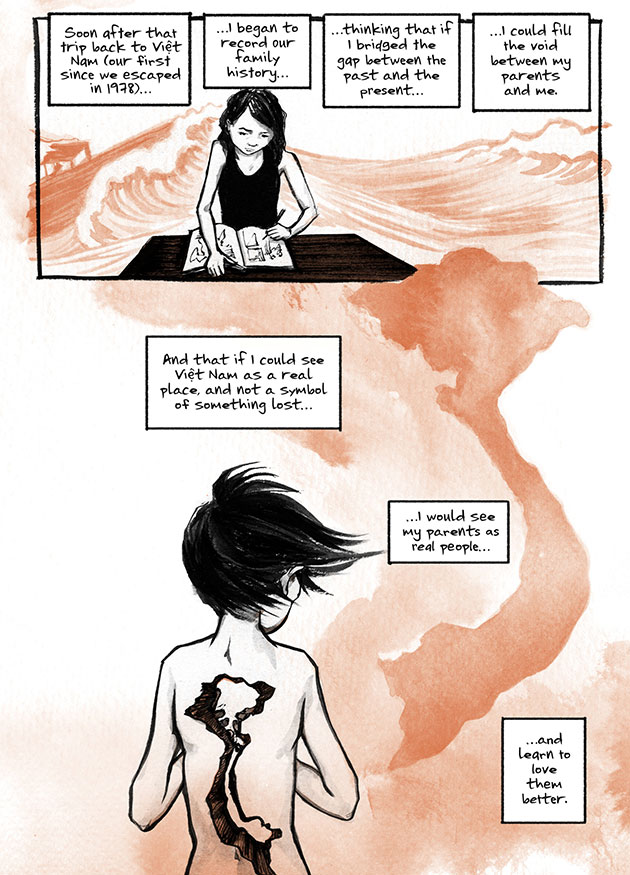

In her debut graphic memoir, The Best We Could Do, Thi Bui traces the story of her family’s displacement from Vietnam in the 1970s. Bui was three years old when she, her parents, and her siblings left South Vietnam by boat and eventually made their way to the United States. Growing up as a refugee in San Diego, California, Bui sensed that the Vietnam War had left a deep psychological scar on her parents, but she rarely heard them talk about it. She was studying studio art in grad school in 2002 when she returned to Vietnam to meet some of her relatives. After the trip prompted her to take a detour from her training, she “got lost in oral history.”

Bui started asking her parents about their past, seeking to understand the forces that caused them leave their home country. As she wrote in The Best We Could Do:

The Best We Could Do

Thi Bui

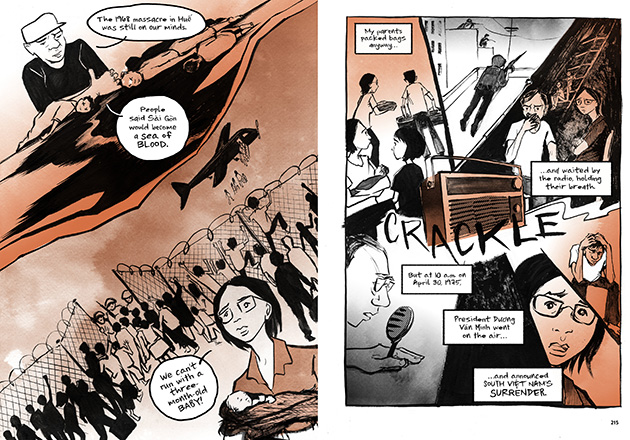

In the process of illustrating her own family’s turbulent story, Bui reveals a personal Vietnam War absent from most history books and soldier narratives. The graphic novel form, which layers narration, dialogue, and visual imagery, reveals with bracing lucidity the complicated dimensions of life during conflict: individuals’ thoughts and fears contrasted with their conversations, for instance, or the government’s promises versus the reality on the ground. The deft inclusion of quotidian details—squabbles over cooking dinner, the quirks that make family members different from one another—allow the immigrant characters to come to life. “It was me creating my own lexicon of images of Vietnamese people that were different from each other,” Bui says. “And in that way, more relatable, more wholly human than I’d seen before.” Bui is a sensitive guide, giving the harrowing personal journey context as she reflects on the power of long-ago decisions over her life today.

The Best We Could Do

Thi Bui

Bui’s next project will take her back to Vietnam where she will tell the stories of farmers affected by climate change. I caught up with her this summer; here are some of her thoughts about the process of creating the The Best We Could Do.

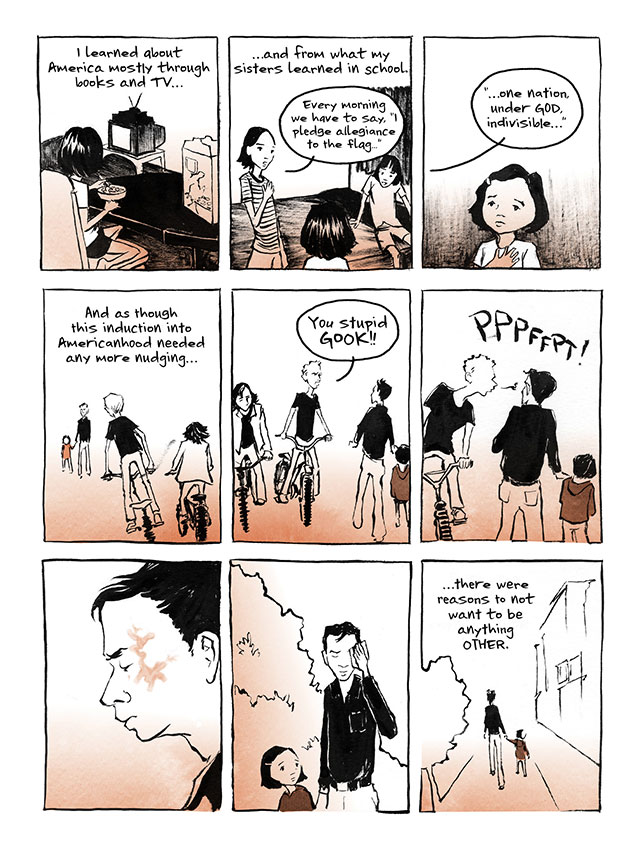

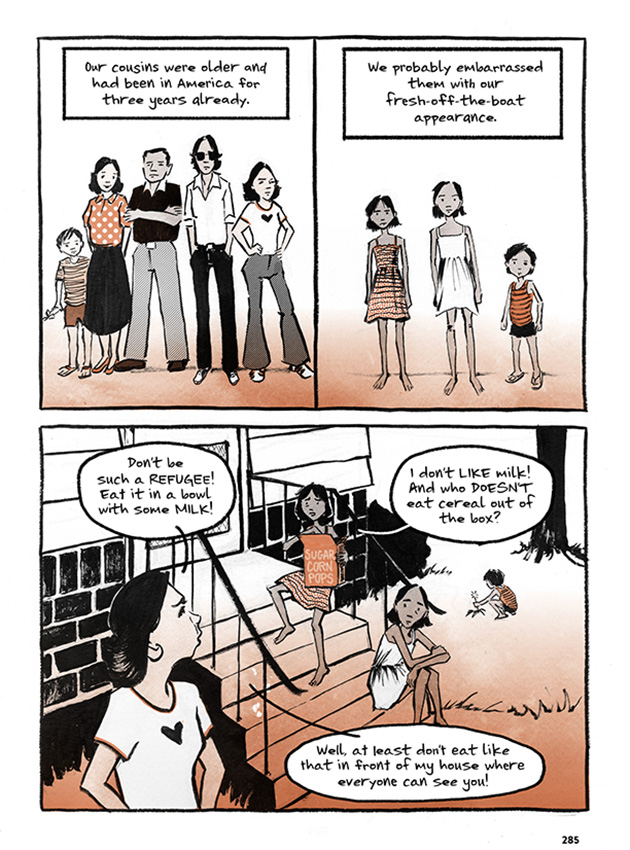

What creating the book taught her about the legacy of growing up as a refugee: “When I was a kid it was hard to not fit in. The simple things that you just don’t want to have happen to you as a kid: people laughing at the food that you bring to school or the clothes you wear or your parents don’t speak perfect English. And I think it was hard for me to grow up with a dad who was so depressed and so displaced from his own former status.

I grew up with a sense of loss of a country that should have been mine but wasn’t. That clock on the wall in the shape of Vietnam that a lot of families had—I always imagine there’s a hole in my chest the shape of Vietnam. And there were times that the displacement felt like the wind blowing through. But when I had a chance to go back to Vietnam as a young adult, I realized that there was a concept that I had created for myself and that wasn’t necessarily true or at least not in the ways that I thought. It wasn’t a country that I lost that I could ever gain back. It was a country that changed over the course of my parents’ lives, and they became incompatible with that country. So really it wasn’t my country at all by the time I was born there. But for me that means that I have to choose where my home is, and I have to make it my home. And I have to convince other people who might see me as a foreigner that, ‘No, this actually is my home.’ I’m like a little snail with my home on my back.”

The Best We Could Do

Thi Bui

Why she decided to tell her story in the form of a graphic novel: “When I started, I had a lot of single pages with one big image and then the text kind of around it. There was something about spending time with the characters just doing things, rather than standing still and saying things. It was like more engrossing. It did a better job of humanizing the characters and countering whatever stereotypes you gather over the years watching a bad Vietnam War movie or two. So it was me creating my own lexicon of images of Vietnamese people that were different from each other. And in that way, more relatable, more wholly human than I’d seen before.”

On watching “bad Vietnam War movies” as a kid: “American stereotypes of Vietnamese people during the Vietnam War were very upsetting to me. I was able to deal with them directly in a couple of panels in the book. My revenge against all of that is to preserve the rest of the real estate of my book for my own interpretations of Vietnamese people’s experiences.”

Why she landed on sepia as the book’s main color: “I was thinking about the color of dust that comes off of bricks. There’s a love that I have of old photographs. In my childhood memories of me and my siblings in San Diego, there was a warm afternoon light. I was going for something nostalgic and sentimental and warm.”