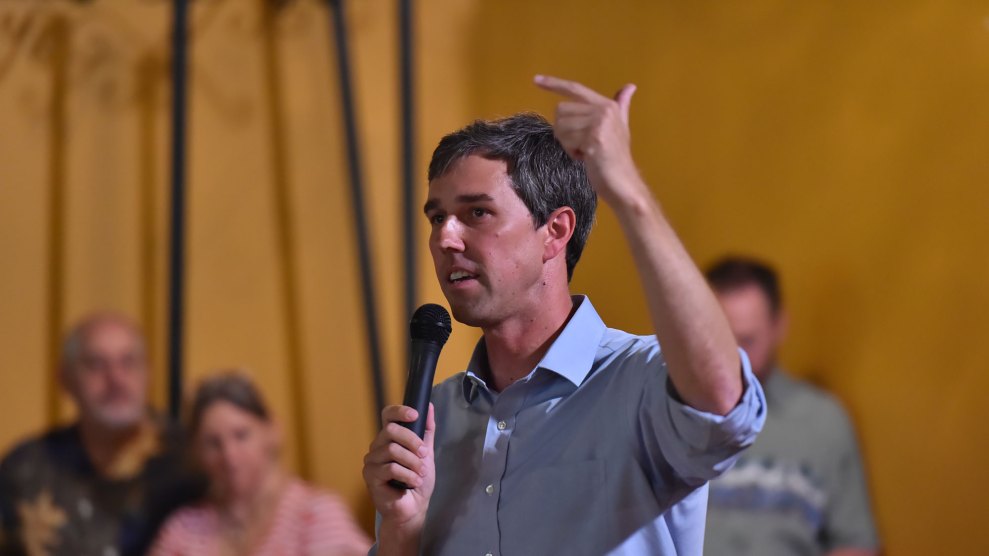

Robin Jerstad/Zuma Wire

Texas Democratic Rep. Beto O’Rourke, whom I profiled for the September/October issue of the magazine, is an interesting guy. A free-spirited former punk-rock guitarist who won his seat by challenging a powerful incumbent congressman over the drug war, O’Rourke is a moonshot candidate for a moonshot race—he’s the Democrat trying to take Ted Cruz’s Senate seat in next year’s midterm election. The race holds a unique significance because, on paper anyway, Texas may offer Democrats’ most likely shot at picking up a 51st Senate seat. But the campaign will also be a test of just how fast Texas is changing politically two years into the Trump era—or if it’s changing at all. One thing O’Rourke won’t have to deal with is the burden of high expectations; Republicans have won 123 consecutive statewide races in Texas dating back to 1996, and no one from El Paso has ever been elected to statewide office.

There’s a lot packed into the piece, but there’s also a lot from our wide-ranging conversation that ended up on the cutting-room floor. Here’s a bit more from O’Rourke, on the future of the Democratic Party, his opponent, and (improbably enough) Icelandic sagas.

On what O’Rourke learned from Bernie Sanders:

Bernie [spoke to the House Democratic Caucus] at the end of the primaries, when I think it was a foregone and maybe even a mathematical conclusion that he did not have a chance to win. People were really pissed off and it’s just hostility in the room. I could also tell he did not really want to be there. I think, with some justification, my colleagues were saying to him, Hey, you’re holding the party and this process hostage, you know; get behind our presumptive nominee and let’s all unify. And I think there’s a lot to that argument, but he said something—he said, “You know, it can’t be enough to just call out what we don’t like, we’ve got to be able to rally behind some things that are really compelling that are exciting to people, that describe the future that we want to help deliver for this country.” I think he was making the point like—I don’t know how old he is—Why do you have thousands of people who have never been involved in the political process before coming to hear a 70-something-year-old socialist all over the country? And he was making the point,

It’s not about me, it’s not about what we’re against, it’s the things that we’re for that people want to see in their lives and they’re willing to work for. So that moment always stuck with me. I think he made a really good prescient case for how we should be running.

On what he’s learned about his opponent:

To rise from not being known to anyone five years ago, four years ago, to being a first-term junior senator, to being a major-party primary presidential candidate and almost winning the thing was really impressive.

But I also saw that [Cruz] essentially spent the three and a half years until the Republican primary was decided running for president. And that came at the cost of serving Texas. It’s clear in hindsight that shutting down the government was part of building that national profile and pursuing higher public office and distinguishing himself amongst his primary competition, and it really hurt a lot of people that he otherwise could have been serving.

I just met, for example, a veteran from San Antonio who was badly wounded in Afghanistan and shared with me the horrifying story of learning that there were men who lost their lives in Afghanistan during that shutdown whose—until a private foundation stepped in, I think it was the Fisher House—parents were unable to fly out to meet their bodies because the death and burial benefits could not be processed. And unwilling to put his country over party or ideology or his personal advancement, Ted Cruz shut down the government and kept it shut down, despite the pleading of these families and other concerned Americans who wanted to make sure we were fulfilling our commitments to those who arguably deserve it more than anyone else in this country. For me that was—for us, for this country—that was a real consequence of this.

So, on the one hand, he did something just absolutely extraordinary to rise from obscurity to very close to the Republican nomination for the presidency. But it came at a significant cost.

On the roots of Donald Trump’s nativism:

There’s a great book, if you haven’t read [it], Ringside Seat to a Revolution. It’s by this guy David Romo from El Paso. And it just shows you how interesting El Paso and Juarez are. He basically writes from the premise that El Paso was really the starting point and an incredibly important part of the Mexican Revolution. The battle for Juarez. It’s where [Francisco] Madero lived. It’s where Pancho Villa lived. It’s where the revolution was planned and headquartered. It’s where the novel of the Mexican Revolution, Los De Abajo, was written.

It was a city of international intrigue and revolution and exciting intellectual developments on both sides of the border, and it’s also a city that was one of the first in the nation to outlaw marijuana based on what “Mexicans”—who could be Mexican Americans—do when they’re high on marijuana. Allegedly. And it’s also the city where our mayor at the time implemented a program of disinfecting Mexicans as they came across the border—so like, literally making them take their clothes off, gassing them, delousing them.

That way of viewing Mexicans as a threat—you have Dan Patrick who’s our lieutenant governor who talks about people from Mexico and from Central America bringing Third World diseases to our country. You look at history, far back and long enough, and you see the strains of nativism and xenophobia and racism that are exhibiting themselves today in America. But you also look at history and you realize that while we have at times a hard time coming to terms with our connection to the rest of the world, I think we generally are moving in the right direction.

On Beowulf—and drone warfare:

I started as a film major and I remember getting to a class with [film critic] Andrew Sarris and other cool people who had done amazing things in film criticism or who were writing about films, but I was frustrated that you didn’t get to make films until you went into the graduate programs. Then I became very interested in ancient studies, Greek and ancient Roman, and then literature, and kind of world literature. I took Spanish-language literature classes that focused on Mexico and South America in Spanish. [I] took Russian literature classes, read Fathers and Sons by Turgenev, obviously in English translation, loved it; read what’s-his-name, Snorri Sturluson, who’s the Homer of Iceland, and the Icelandic sagas; read the Mabinogion. Just, like, the traditions and the Irish, you know, myths of horses and people and horse-people, which is fascinating to me. I read The Odyssey in high school and reread it; read Beowulf and reread it.

I love these amazing stories of just adventure and war and these stories that seemed eternal. They’d keep kind of playing out in other stories that are told, and even the stories themselves are about how these stories keep replaying, like Beowulf, like just the violence never ends, and even when there’s this wedding party and they bring these two opposing clans together because there’s gonna be another marriage, they end up getting drunk and slaughtering each other. And then that violence begets more violence. Just fundamental issues that we wrestle with here—why have we been at war in the Middle East for 26 years straight? And when will that end? And dropping missiles on people with drones, does that create more enemies? Does that achieve our goals?

On single-payer health care:

If you don’t have your health, if you can’t see a doctor or you cant afford medication if you need medication, if your only resort is to go the emergency room because you’re desperate, its going to be really bad for you. It’s going to undermine your potential, and by extension, the potential of the state and of the country.

And for that reason alone, we have to move beyond private insurance companies dictating who can and can’t get health care and making life miserable for the doctors who are trying to deliver it as they try to negotiate between all these different health care insurers. We have to have something like Medicare for everybody. Medicare is the best health care program in the country that—and I’m not an expert—but that I can find in terms of the satisfaction of those who have Medicare, of the costs associated with it. I think it has like a 2 percent administrative cost compared to private insurers. It’s only like 18 percent [of the population], and it’s probably one of the most popular successful government programs of all time! And no solution’s perfect. To quote the president, “This stuff’s really complex.”

Now, I am willing and have to—in order to do the best for the people I represent and serve—compromise on something short of that. That’s where I want to get to, and it’s important that people know where I want to get to: a single-payer system that delivers much better health care for all Texans and does so at a much lower cost. Some people have used the fact that it’s unlikely we will get there in this current administration as a reason for not saying where they want to get to, but if that were the case then I shouldn’t say that I want to get to comprehensive immigration reform or any number of things. I think its important for people to know where we want to get to. But if we can’t get there now—and I’m not giving up on us getting there, but if we can’t get there now—I am very open to the compromises that may be necessary to get something better than what we have. If there was some way that we could expand Medicaid in Texas, for example; we were one of the states that chose not to. I’d be a fool not to look at that, and it would be fine with me if that were an idea from President Trump himself, or from Governor Abbott. If it’s gonna help more Texans than the Affordable Care Act and drive down costs and improve outcomes, absolutely, I’m gonna take a look at it.

(O’Rourke has not co-sponsored Michigan Rep. John Conyers’ Medicare-for-all bill in the House, nor has he endorsed Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ single-payer proposal in the Senate, but he reiterated to the Texas Observer in September that he was supportive of the idea and in the process of writing his own bill.)

On how often he’s talked with Cruz:

Two conversations. One conversation in a group setting around the government shutdown—this was in 2013—and then from that I asked if I could follow up and meet with him and talk with him about some concerns I had. That’s been the extent of it. Now, that’s me personally; our office may have reached out to his office on things—Hey, would you want to sponsor this, or, Here’s an issue that we’re concerned with. I’ve had, frankly, a much more productive relationship with [Texas’s other Republican senator] John Cornyn, with whom I’ve introduced legislation, whom I have called when I’ve got a concern about, you know, the Muslim ban or the wall or US–Mexico relations in general.

This interview has been edited in parts and condensed for clarity.