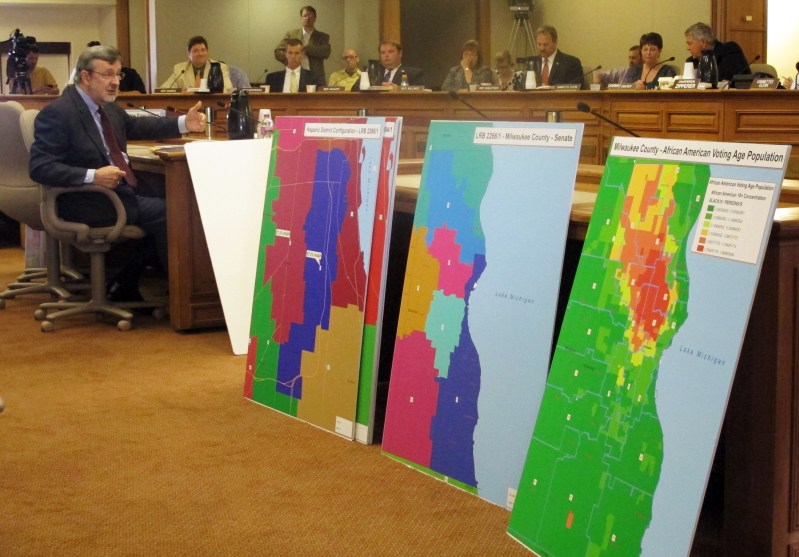

Former Rep. Dave Obey (D-Wis.) testifies at a hearing on Republican redistricting plans in Madison in 2011.Scott Bauer/AP

John Steinbrink, a 68-year-old corn and soybean farmer, represented Kenosha and the surrounding area in the Wisconsin legislature for 16 years. A Democrat, he won his 2010 reelection race with more than 99 percent of the vote in the blue-tinted district. But after Republicans gained control of the Wisconsin legislature in the 2010 election and unilaterally redrew the state’s political maps for the first time in more than 40 years, Steinbrink’s farm was placed in a new district, held by a Republican incumbent, that no longer contained the city of Kenosha but instead its red exurbs and rural farmland.

“It was much more conservative, much more Republican,” he says. He lost reelection to incumbent Rep. Samantha Kerkman, a strong supporter of Gov. Scott Walker, in 2012 by 11 points. “I kind of knew it wouldn’t work out because of how the lines were drawn,” he says.

Republicans replicated this partisan gerrymandering across Wisconsin, turning a purple state into a solidly red one at the state legislative and congressional level, even as voters across the state remained about evenly split. In 2012, the same year Steinbrink was defeated, Barack Obama carried Wisconsin by seven points and Democratic legislative candidates received 51.4 percent of the statewide vote, but Republican candidates won 60 of 99 seats in the state assembly. The hard-right policies pursued by Republicans in Wisconsin—dismantling unions, restricting voting rights, undermining environmental protections, deregulating campaign finance laws—are the result of the creation of safe Republican seats that are unwinnable for Democrats in even the best of times, Steinbrink says.

Now Democrats are challenging Wisconsin’s legislative gerrymander before the Supreme Court in a case with far-reaching ramifications. In November 2016, a three-judge federal court in Wisconsin struck down the assembly maps as “an unconstitutional political gerrymander” that was “intended to burden the representational rights of Democratic voters…by impeding their ability to translate their votes into legislative seats.”

The Supreme Court temporarily blocked the ruling from going into effect in a 5-4 decision and will hear oral arguments on Tuesday in the case, Gill v. Whitford. The court has long ruled that politicians cannot draw districts that deny representation to racial minorities, but it has never outlawed partisan gerrymandering, where voters are denied representation because of their party affiliation. Indeed, in a 2004 case from Pennsylvania, the late Justice Antonin Scalia wrote for the majority that such claims should never be reviewed by the court. Justice Anthony Kennedy, the court’s frequent swing vote, sided with Scalia but gave voting rights advocates a glimmer of hope when he wrote in a concurring opinion, “I would not foreclose all possibility of judicial relief if some limited and precise rationale were found to correct an established violation of the Constitution in some redistricting cases.” In other words, Kennedy would be open to striking down extreme partisan gerrymanders if the court could agree on a standard to do so, like in racial gerrymandering cases where it’s possible to prove a clear violation of the Voting Rights Act.

To persuade Kennedy, plaintiffs in the case developed a novel test called the “efficiency gap” to measure the number of “wasted” votes for a party, such as when voters are placed in deep-red or deep-blue districts where they have no chance of influencing the outcome. The two scholars who developed the efficiency gap, Nicholas Stephanopoulos of the University of Chicago and Eric McGhee of the Public Policy Institute of California, found that “the plans in effect today” in states like Wisconsin “are the most extreme gerrymanders in modern history.”

Following the 2010 election, Republicans had full control of the redistricting process for state legislative and US House seats in 21 states, compared to eight states for Democrats. The result was that Republicans had a virtual lock on four times as many state legislative and US House seats as Democrats did. Republicans hold as many as 22 additional House seats because of partisan gerrymandering, according to an analysis by the Associated Press—nearly the same margin as the 24 seats Democrats need to flip to take back the House. (During the 2012 election, Democratic House candidates won 1.4 million more votes nationally than Republicans, but the GOP won 33 more seats.) According to a recent analysis by Decision Desk HQ, Democrats are projected to win 54 percent of votes for the House in 2018 but pick up only 47 percent of seats.

Though gerrymandering has benefitted Republicans more in recent years, some prominent Republicans are urging the Supreme Court to curb partisan gerrymandering for the first time. “It entrenches political parties against popular will; it polarizes legislatures and creates gridlock; and it engenders voter cynicism about a political system that has been rigged to achieve predetermined electoral results, potentially in opposition to their will,” Bob Dole, John Kasich, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and nearly a dozen other GOP officials said in a brief submitted to the court. “Politicians now select their voters, instead of voters electing politicians.” Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), along with a bipartisan group of 36 current or former members of the House of Representatives, also asked the Court to rule against gerrymandering.

In its own brief, Wisconsin dismissed the plaintiffs’ arguments as “social-science hodgepodge.” The Wisconsin legislature said in a supporting brief that “partisan gerrymandering claims will cause unprecedented levels of federal intrusion into the state redistricting process.”

A ruling against Wisconsin would be one of the most significant victories for voting rights in decades, opening the door to many more challenges to gerrymandering across the country, in both red and blue states where maps were clearly drawn for a political advantage.

A ruling for Wisconsin, alternatively, would virtually guarantee many more partisan gerrymanders in the future. Republicans would claim they are denying representation to Democratic voters for partisan, not racial, reasons. After North Carolina’s redistricting maps for the state legislature were struck down as unconstitutional racial gerrymanders by a federal court in 2016, the Republican legislature passed new maps in August that professed to ignore race but still preserved huge Republican majorities, according to an analysis by the Campaign Legal Center using the efficiency gap. Those maps would almost certainly be challenged if Wisconsin loses this case but remain in place if it wins.

Both sides agree that the outcome in Wisconsin will reverberate far beyond the Badger State. “We’re hoping to win in Wisconsin,” says Ruth Greenwood of the Campaign Legal Center, which helped spearhead the lawsuit, “but also set a precedent that partisan gerrymandering is not okay.”