Republican state senators in North Carolina review historical maps in February 2016. Corey Lowenstein/The News & Observer via AP, File

Democratic optimism about the 2018 midterm elections is at its zenith. Democrat Conor Lamb’s victory in Pennsylvania’s 18th congressional district, a GOP-friendly area that President Donald Trump won by 20 points, caused Democratic expectations to soar. CNN’s Chris Cillizza wrote in a breathless article full of exclamation points that 119 Republicans whose districts are less red than PA-18 could lose their jobs in November.

But all this optimism may overlook a key factor: the impact of gerrymandering. A new report from the Brennan Center for Justice calculates just how much of a landslide Democrats will need in order to win in districts that were drawn specifically to withstand Democratic waves and elect Republicans. The result, report co-author Michael Li says, should be a “reality check” for Democrats.

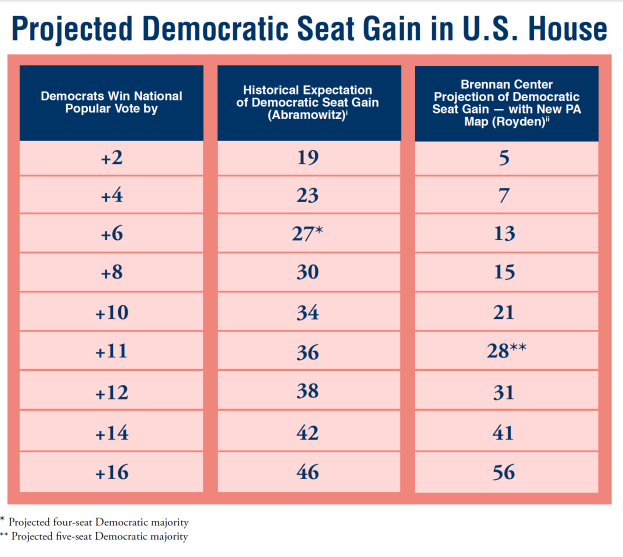

Democrats need a net gain of 24 seats to take back the House of Representatives. In a typical election, according to an analysis of midterm data from 1946 to 2014 by political scientist Alan Abramowitz, a six-point edge in the popular vote in November would net them 27 seats. Polls show that kind of performance is within reach; voters have expressed a preference for electing Democrats to Congress this fall by an average of seven points, according to Real Clear Politics. But factor in Republicans’ built-in advantage in districts across the country and those gains are cut in half. According to the Brennan Center report, a six-point win with today’s political maps would earn Democrats just 13 seats. In order to take back the House, Democrats would need to win the popular vote by 11 points—an enormous margin in American politics today.

The reason for this monumental hurdle is “structural barriers put in place by gerrymandering,” says Li, an attorney with the Brennan Center who focuses on redistricting. “Which is not to say Democrats don’t take the majority. It’s just, it’s going to be a smaller majority and it’s going to be a hard slog in ways that it wasn’t necessarily even as recently as a decade ago.”

In 2006, considered a wave election for Democrats, the party retook the House with a national margin of less than six points. The report predicts 2018 could be more like last year’s elections in Virginia, when Democrats won statewide by 11 points but still failed to capture the state’s House of Delegates.

Gerrymandering is nothing new in American politics, but the degree to which it was implemented across the country after the last census in 2010 is crippling to Democrats. Republicans swept into power in statehouses across the country that year and drew maps to entrench their majorities. Unlike in past redistricting cycles, Republicans in 2010 had access to computer modeling and data analysis that allowed them to draw some of the most extreme and resilient gerrymanders in the country’s history.

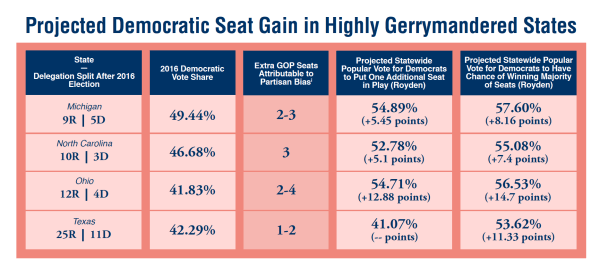

This was particularly true in purple states that should be responsive to political shifts. In years when Democrats do well, purple states go blue; in good years for Republicans, they turn red. But many of these large, purple states have been gerrymandered so that they no longer respond to political changes on the district level. The report points to Michigan, North Carolina, and Ohio in particular as states where gerrymandering could cost Democrats the House. It also looks at Texas, a state that, while reliably Republican, contains suburban districts that should swing between the two parties under normal circumstances.

In these gerrymandered purple states, Republicans map-drawers packed Democratic voters into a handful of reliably blue districts. In Ohio, for example, if Democrats won just 26 percent of the vote, they would still win four of the state’s 16 congressional seats. But in order to compete for a fifth seat, the report finds, Democrats would need to win about 55 percent of the statewide vote. In other words, the state could shift nearly 30 points before Democrats netted another seat. “Even if Democrats do better than they did in 2006, 2008″—years when Democrats dominated—”they don’t pick up additional seats,” says Li. “Which is utterly crazy.”

There are always exceptions to the rule. Some districts could outperform expectations due to special circumstances, like those in Pennsylvania’s 18th district this month, where the Republican incumbent resigned amid scandal, setting up a special election with no incumbent and a strong Democratic candidate. Democratic enthusiasm also meant that Lamb was able to raise money from small-dollar donors across the country. But few races in November will have these characteristics. “There can be district-specific dynamics in play that can put more seats in play than our report projects,” says Li. But when it comes to Lamb’s victory, “we shouldn’t allow the exception to transcend the general principle.”

In the past few years, the courts have repeatedly taken up the question of whether extreme gerrymanders pass constitutional muster. The Supreme Court will decide two major gerrymandering cases this term, out of Wisconsin and Maryland, and groups that have fought against gerrymandering hope that the court will finally place a limit on how far map-drawers can go to entrench their party’s power. But in two other cases, involving Texas and North Carolina, even though courts have found that the states’ congressional maps run afoul of the Constitution and civil rights law, the Supreme Court has allowed the gerrymandered maps to stay in place while it weighs those cases. Despite lower-court decisions that ordered Texas and North Carolina to draw new district lines, their maps will remain in effect in the 2018 midterms and possibly in 2020.